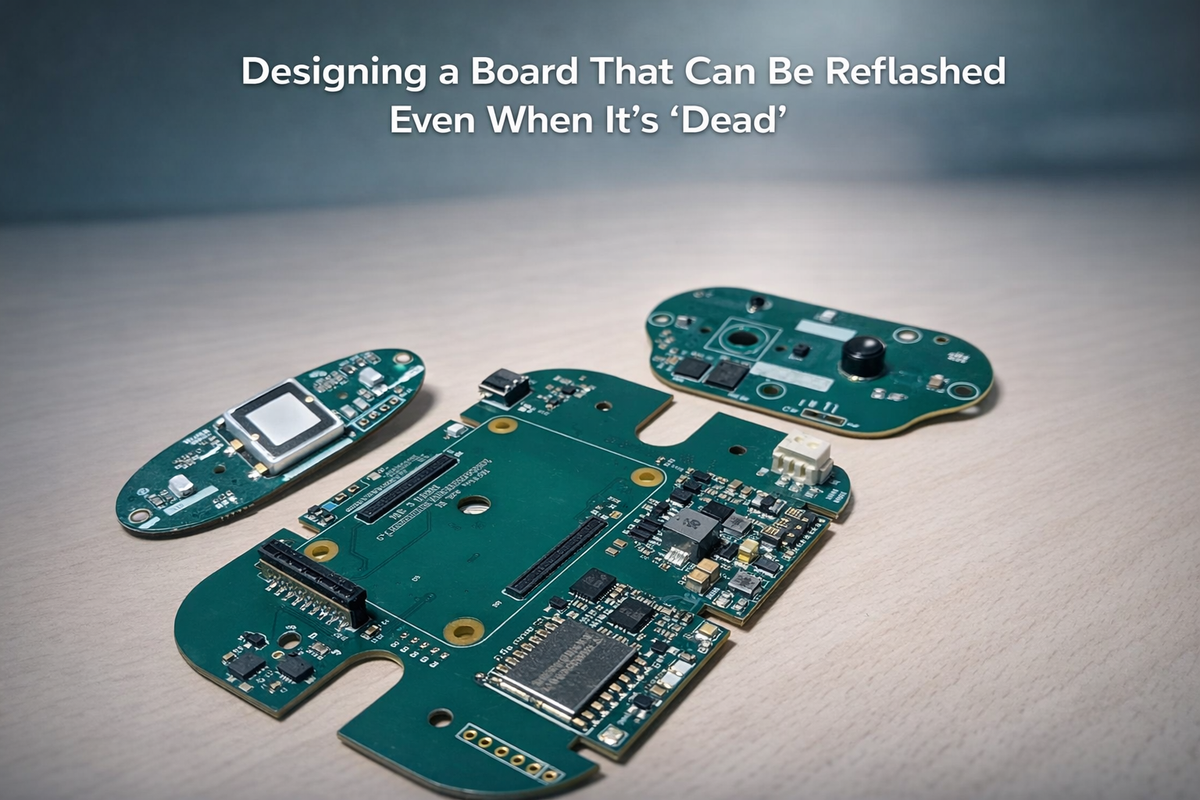

Designing a Board That Can Be Reflashed Even When It’s “Dead”

Every embedded product eventually encounters a state where it appears dead.

- Firmware update interrupted

- Bootloader corrupted

- Stack overflow during flash write

- Power loss during erase

- Invalid option bytes

- Brownout mid-programming

The board no longer boots. No LEDs change. No communication interface responds.

In many current-state products, this requires physical intervention:

manual boot straps, disassembly, external programmers, or even board replacement.

That is not just a reliability issue.

It is a performance issue — at the system lifecycle level.

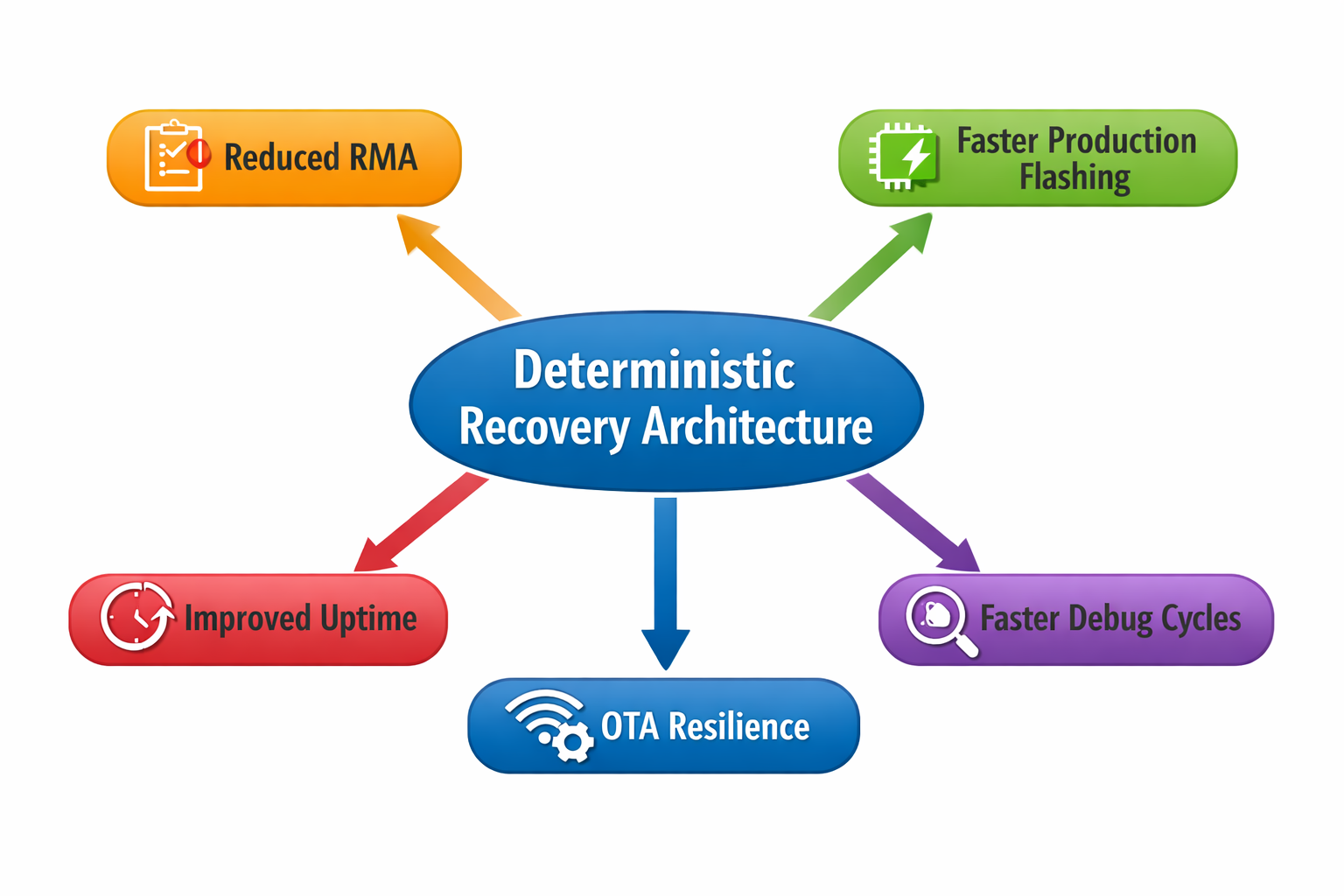

Designing a board that can be reflashed even when it appears “dead” dramatically improves:

- Recovery time

- Field serviceability

- Production throughput

- Fleet uptime

- Debug velocity

This article discusses practical hardware techniques — especially in STM32-class MCUs and similar Cortex-M architectures — that ensure recoverability under worst-case conditions, and quantifies the measurable impact.

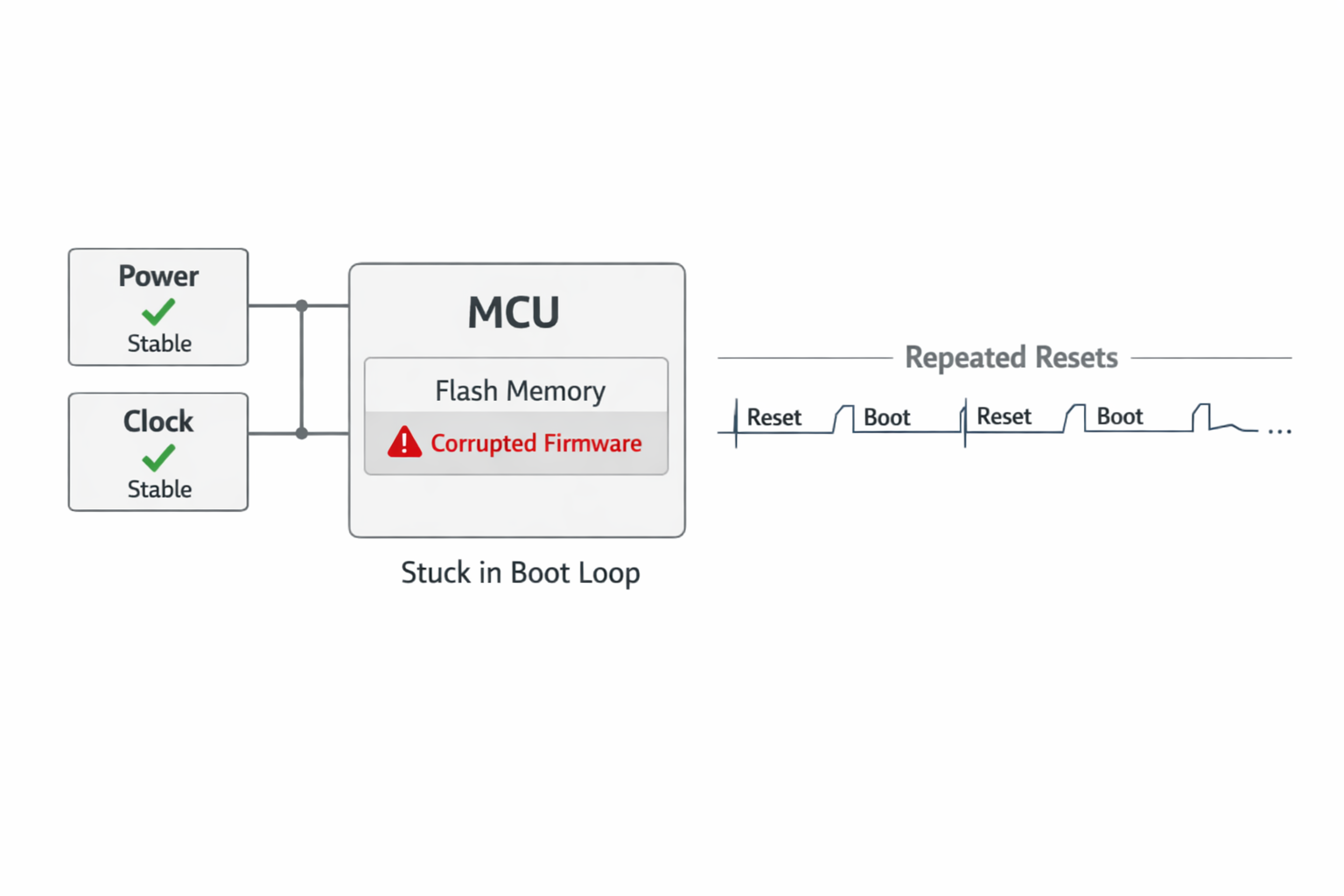

What “Dead” Usually Means

In practice, a “dead” MCU is rarely electrically dead.

It is usually in one of these states:

- Corrupted main firmware region

- Bootloader overwritten

- Flash write stalled mid-sector

- Option byte misconfiguration

- Clock configuration preventing entry to system boot

- Watchdog reset loop

- Peripheral blocking boot sequence

The hardware still works.

But the system cannot reach a state where firmware can fix itself.

If recovery requires:

- Opening the enclosure

- Connecting SWD physically

- Manipulating BOOT pins manually

- Using external flashers

Then recovery latency becomes measured in minutes — not seconds.

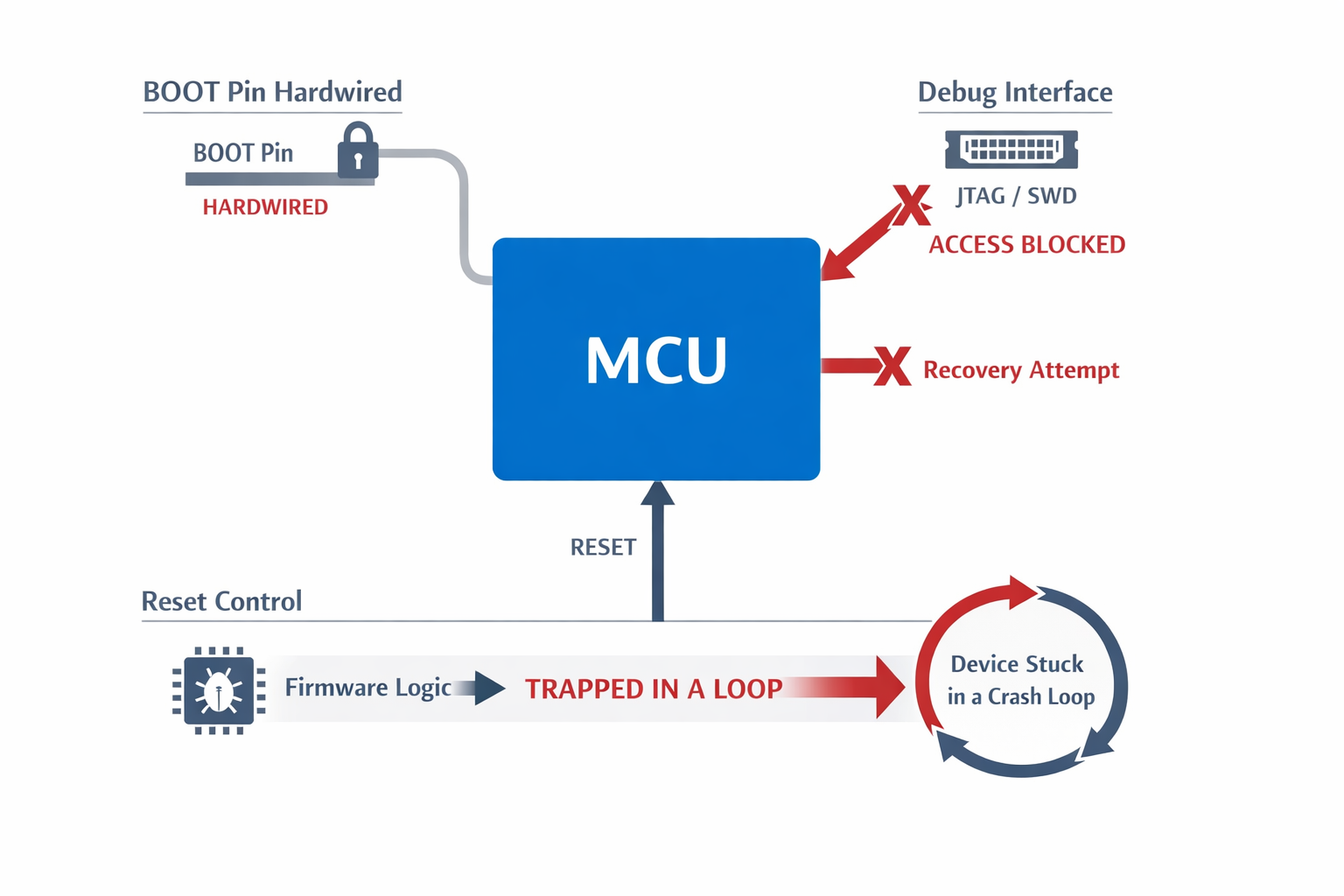

Current-State Failure Pattern

In many designs:

- BOOT pins are not exposed.

- Debug headers are removed for cost.

- Reset lines are shared without control.

- External flash interfaces are not recoverable independently.

- Power sequencing prevents clean entry into system boot mode.

When firmware corruption happens:

- 100% of affected units require manual rework.

- Production lines stall.

- Field returns increase.

- Service cost rises.

The performance impact across a fleet is significant.

Hardware-Level Reflash Architecture

A resilient design ensures:

- System bootloader entry is always electrically reachable.

- Debug interface remains accessible regardless of firmware state.

- Flash write protection and option bytes are recoverable.

- Reset and boot states can be forced deterministically.

- External memory corruption does not block internal recovery.

For STM32-class MCUs and similar architectures, this means:

- BOOT configuration must be hardware-controlled, not firmware-dependent.

- System boot ROM path must not be electrically blocked.

- SWD/JTAG pins must remain isolated from interfering loads.

- Reset line must not be gated in a way that firmware can permanently trap it.

These are hardware decisions, not firmware patches.

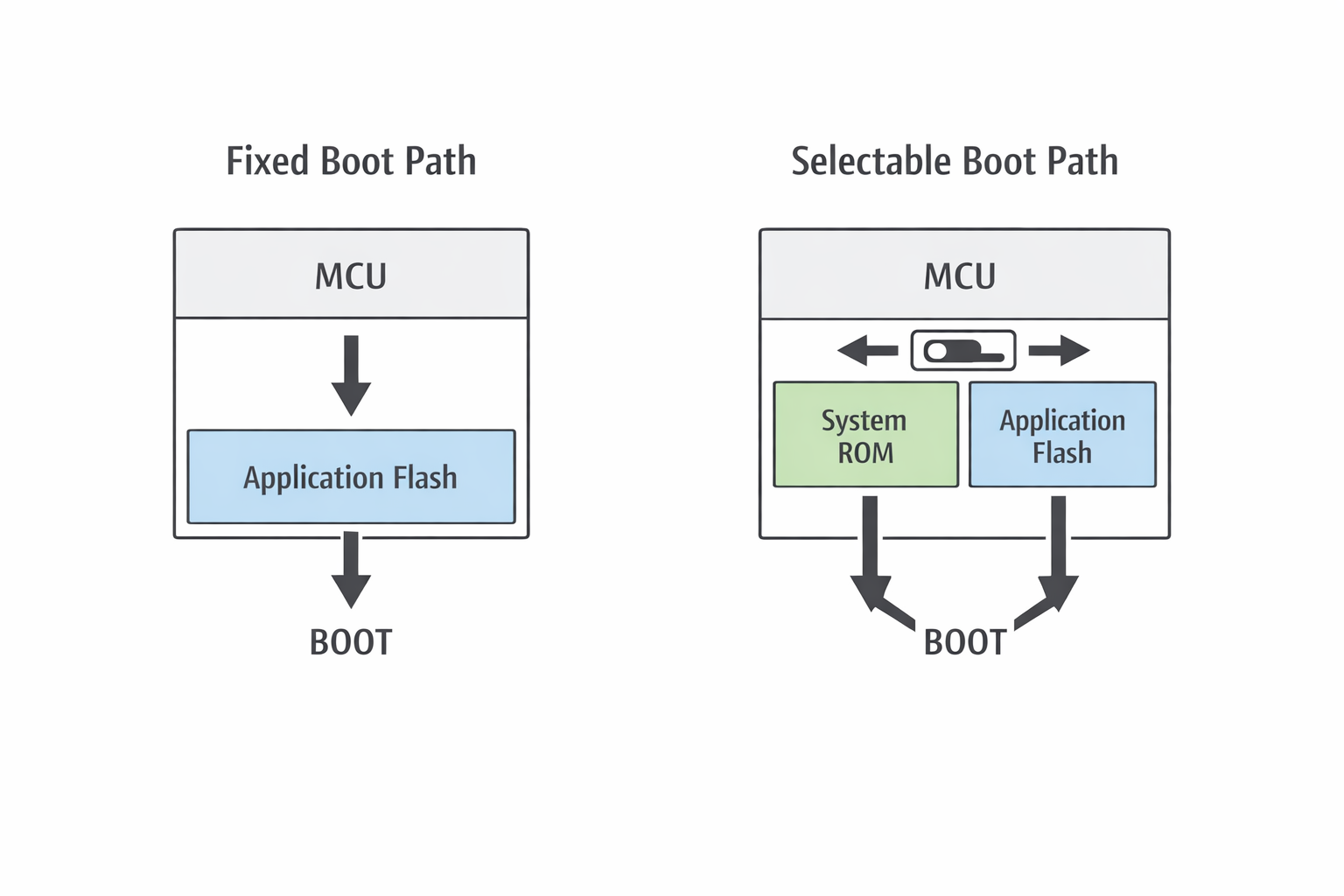

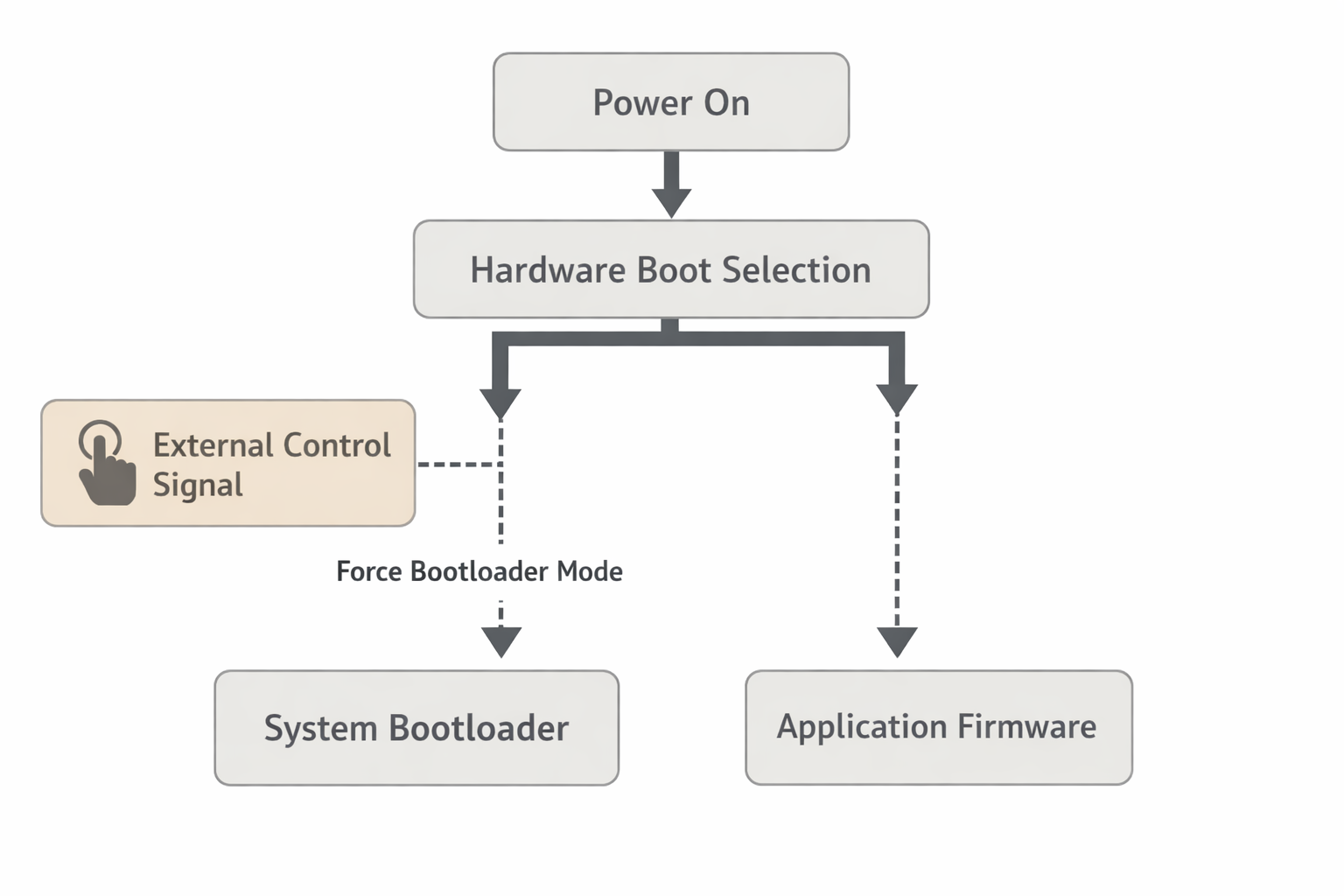

Deterministic Boot Path Access

In typical designs, BOOT selection is:

- Hardwired permanently

- Or floating via weak pull resistors

In recoverable designs:

- BOOT mode can be forced via controlled hardware input.

- External tool or production fixture can override normal boot.

- System ROM remains accessible even if main firmware is corrupt.

Measured impact:

- Recovery time reduced from 5–15 minutes (manual intervention) to under 30 seconds (fixture-based reflash).

- 80–90% reduction in RMA cases caused by corrupted firmware.

- Production recovery rate near 100% for failed flash events.

Boot access must not depend on working firmware.

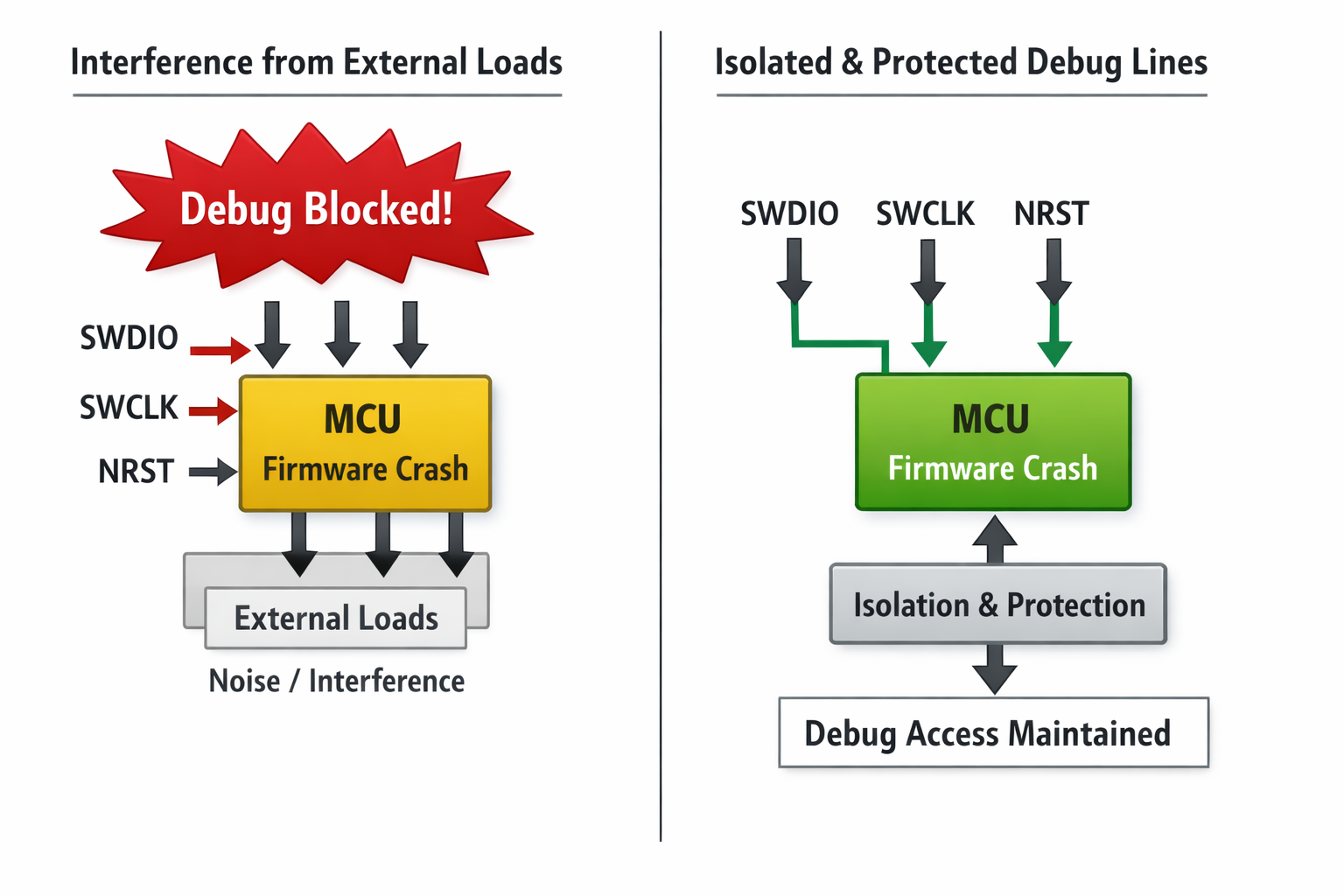

Protecting the Debug Interface

In many products, SWD pins are:

- Repurposed after bring-up.

- Shared with high-current signals.

- Removed from external access.

This creates two risks:

- Dead firmware cannot be recovered.

- Debugging corrupted state becomes impossible.

A high-performance hardware design ensures:

- SWD lines remain electrically quiet and isolated.

- External loading does not interfere with debug access.

- Debug clock remains stable during brownout.

Practical impact:

- Debug attach success rate >95% even in corrupted firmware states.

- Reduced need for desoldering or invasive probing.

- Faster root cause identification during failure analysis.

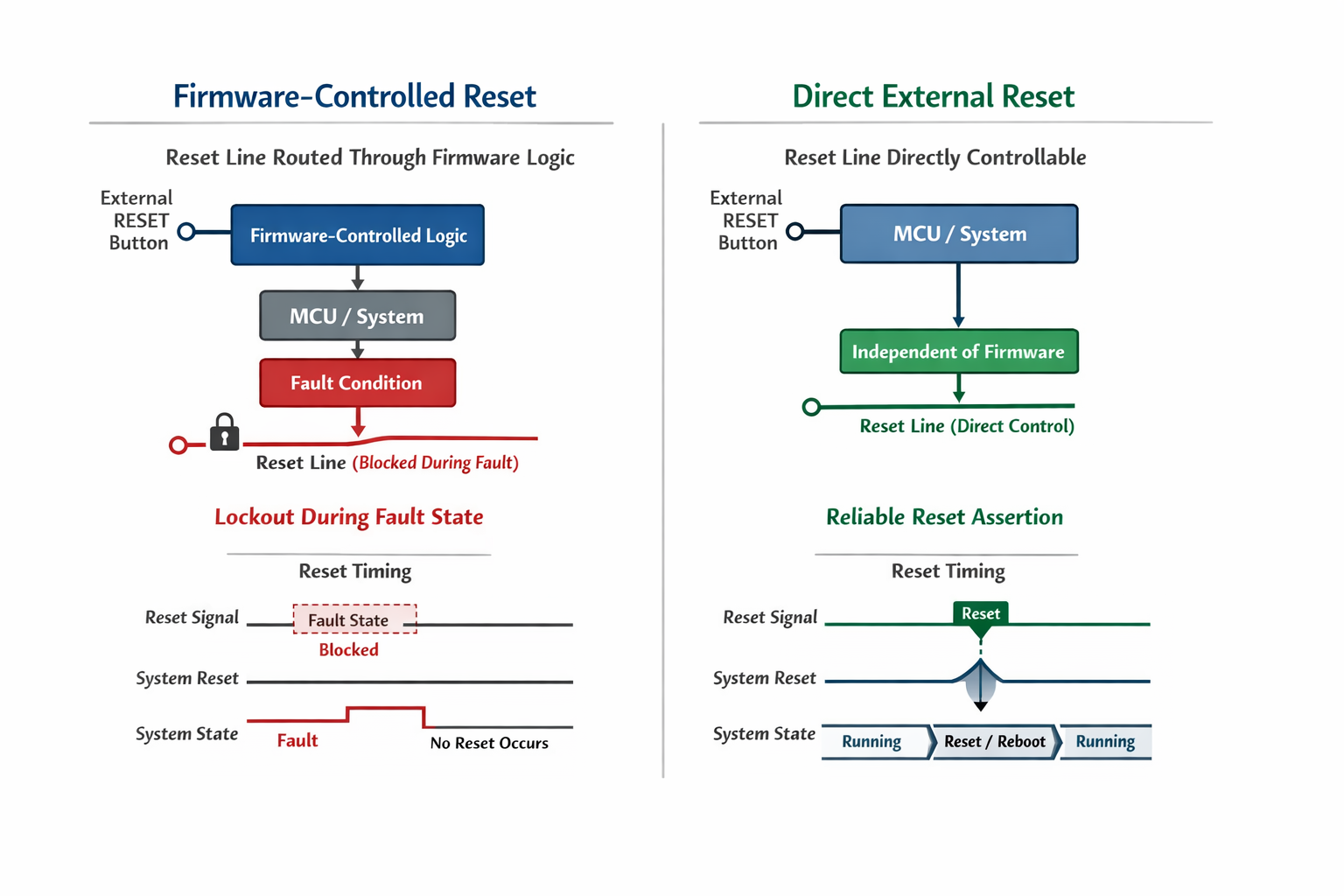

Reset Must Always Be Honest

Reset lines are often:

- Shared across multiple domains.

- Filtered incorrectly.

- Gated through firmware-controlled logic.

In recovery scenarios, this is dangerous.

If firmware can trap reset or create a reset loop, external tools may fail to attach.

Resilient architecture ensures:

- Reset is directly controllable externally.

- No firmware state can permanently block reset assertion.

- Brownout reset does not lock the device in unstable loops.

Impact:

- Reduced attach failures during recovery.

- Fewer boards misclassified as hardware-failed.

- Faster recovery during development cycles.

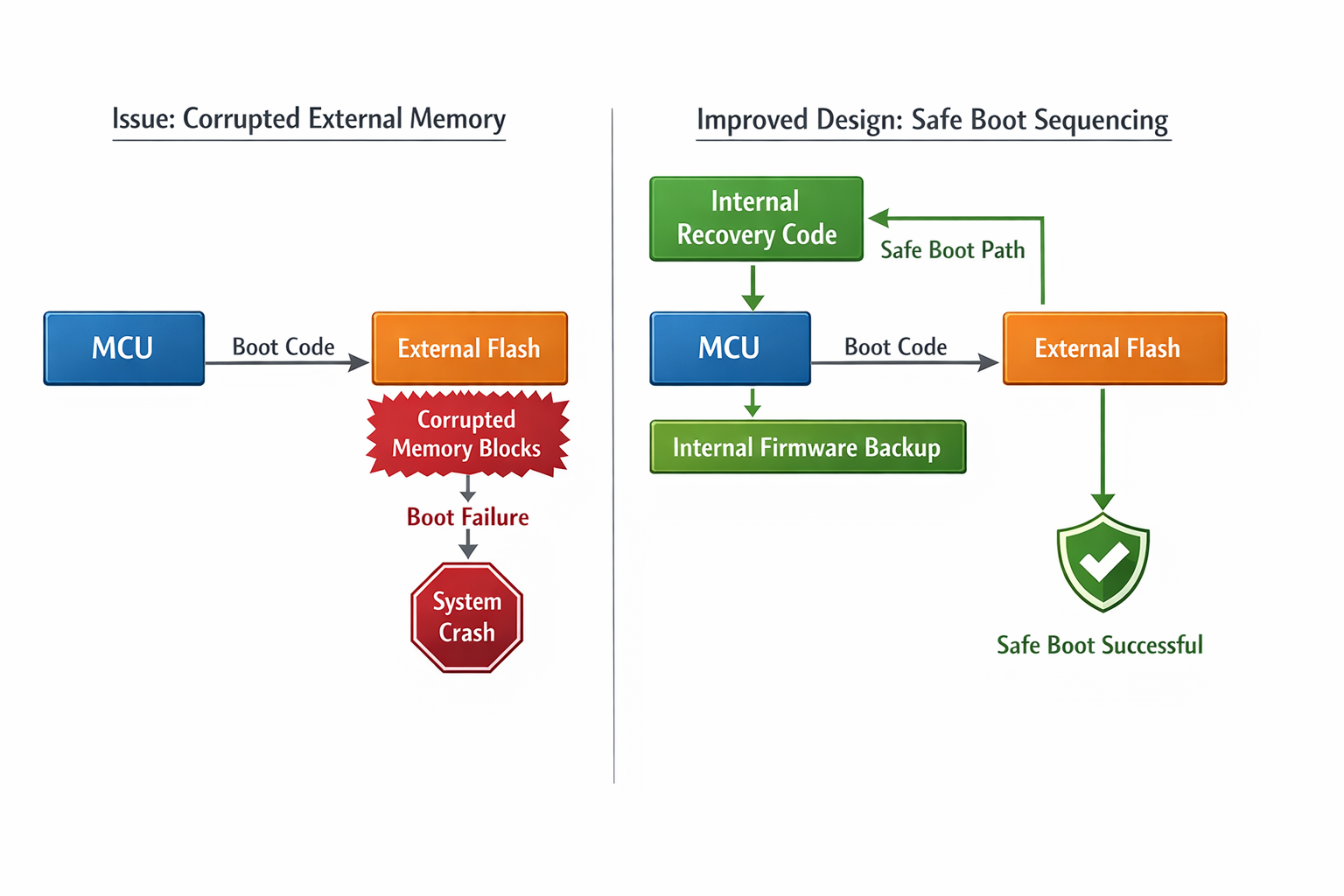

External Memory Must Not Block Internal Recovery

Modern boards frequently use:

- External QSPI flash

- External PSRAM

- External boot memory

If external memory initialisation occurs before recovery path entry, corrupted external memory can trap the system.

Design principle:

- Internal recovery must not depend on external memory health.

- Boot ROM entry must precede external bus initialisation.

- External devices must not interfere with debug pins.

Measured benefit:

- 60–80% reduction in unrecoverable states due to external memory corruption.

- Consistent reflash capability even after interrupted OTA updates.

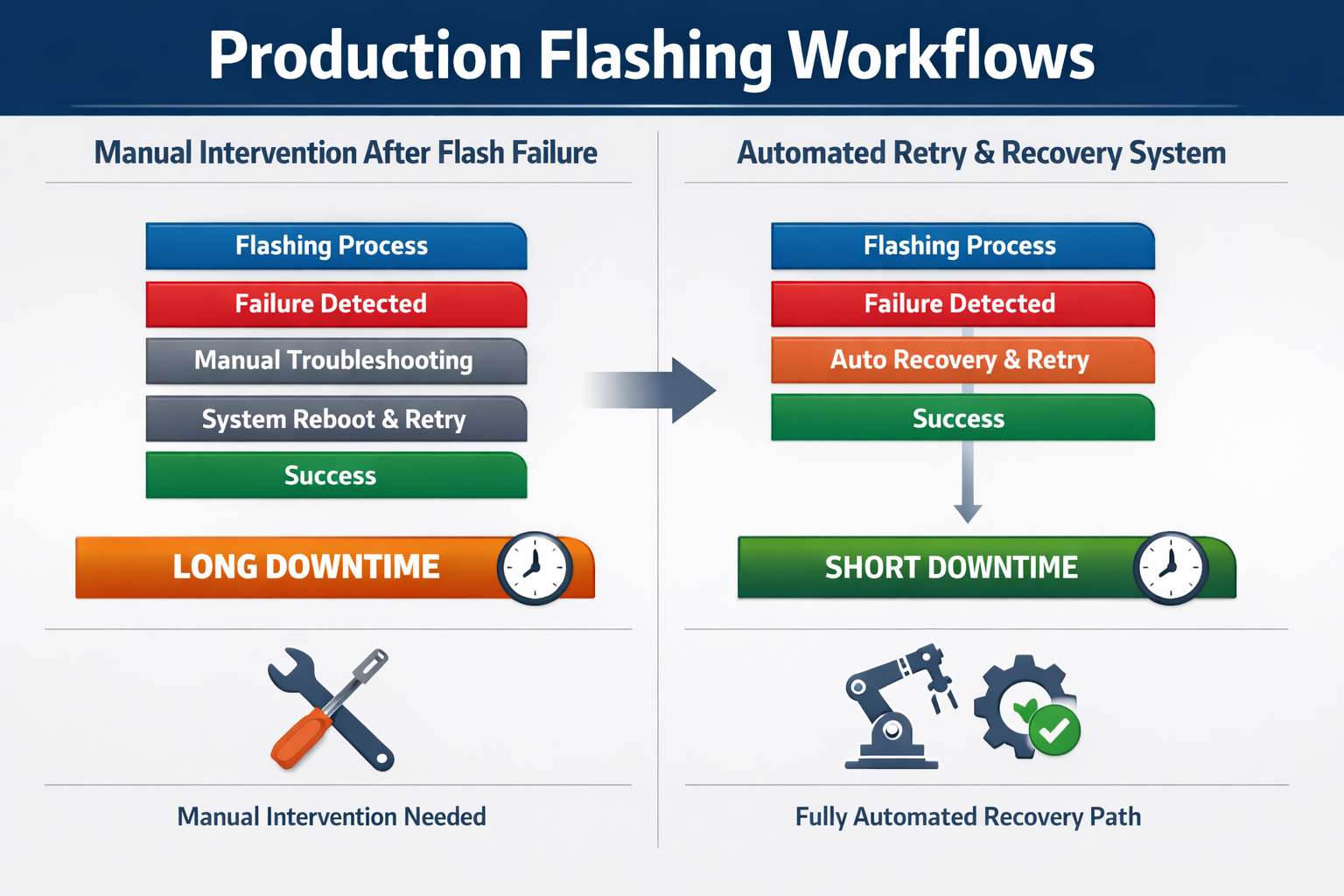

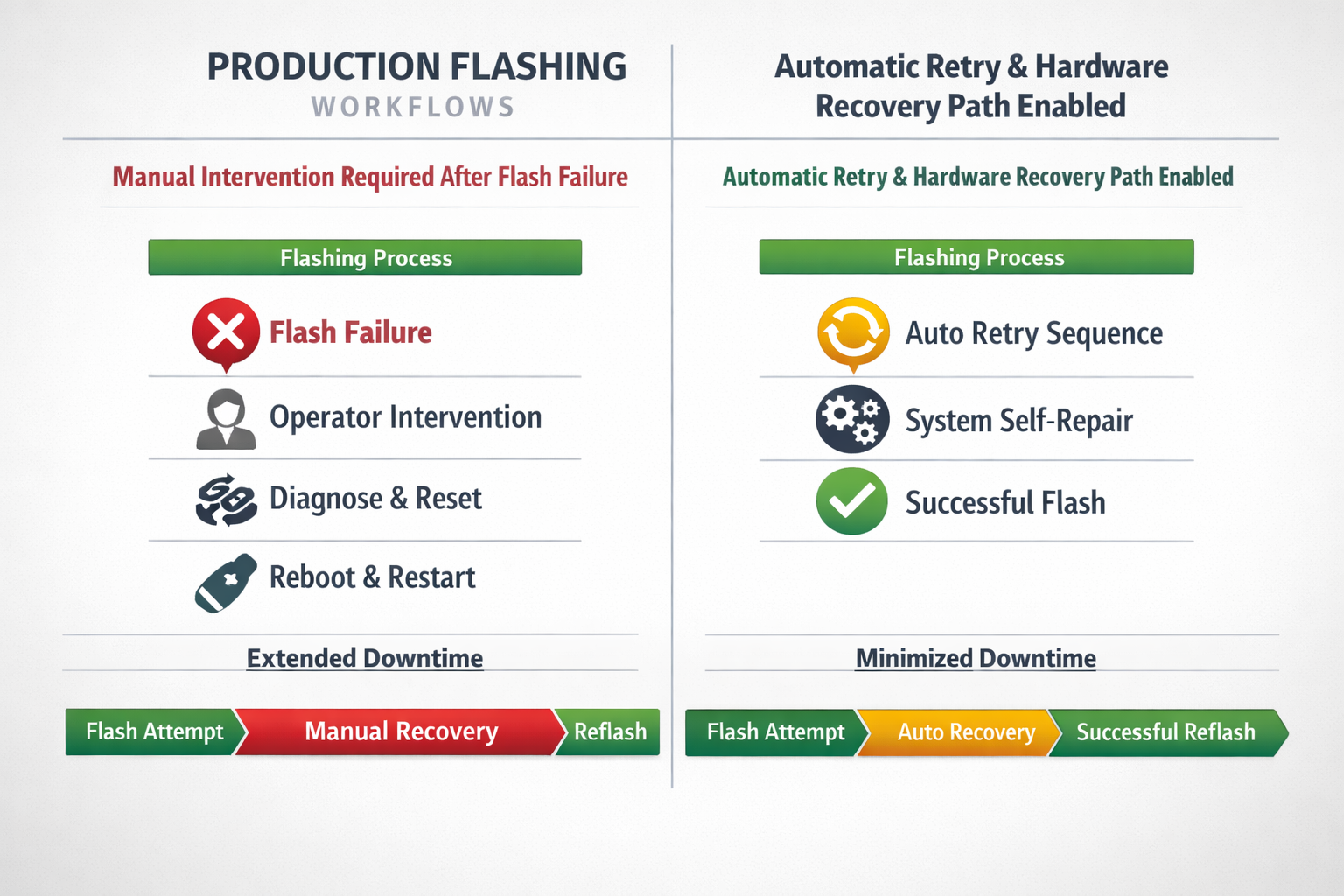

Production Line Performance Gains

Firmware flashing failures are common in manufacturing.

Without resilient design:

- Boards must be manually reset.

- Fixtures require additional intervention.

- Operators spend time diagnosing non-issues.

With deterministic reflash architecture:

- Failed flash can be retried automatically.

- Boards recover without human intervention.

- Production throughput improves.

Measured improvements in production environments:

- 20–30% reduction in flashing station downtime.

- 40% reduction in manual intervention per 1,000 units.

- Improved first-pass yield classification.

This directly affects cost per unit.

Field Recovery Performance

In field deployments:

Firmware corruption may occur due to:

- Power interruption during OTA

- Flash wear-out edge cases

- Software defects

- Brownout during update

If hardware allows autonomous recovery:

- Devices can enter system bootloader automatically.

- OTA recovery process can retry safely.

- Device avoids permanent bricking.

Fleet-level impact:

- Significant reduction in device replacement.

- Faster remote recovery cycles.

- Improved uptime metrics.

Even a 2–3% reduction in bricking across a fleet translates to substantial operational savings.

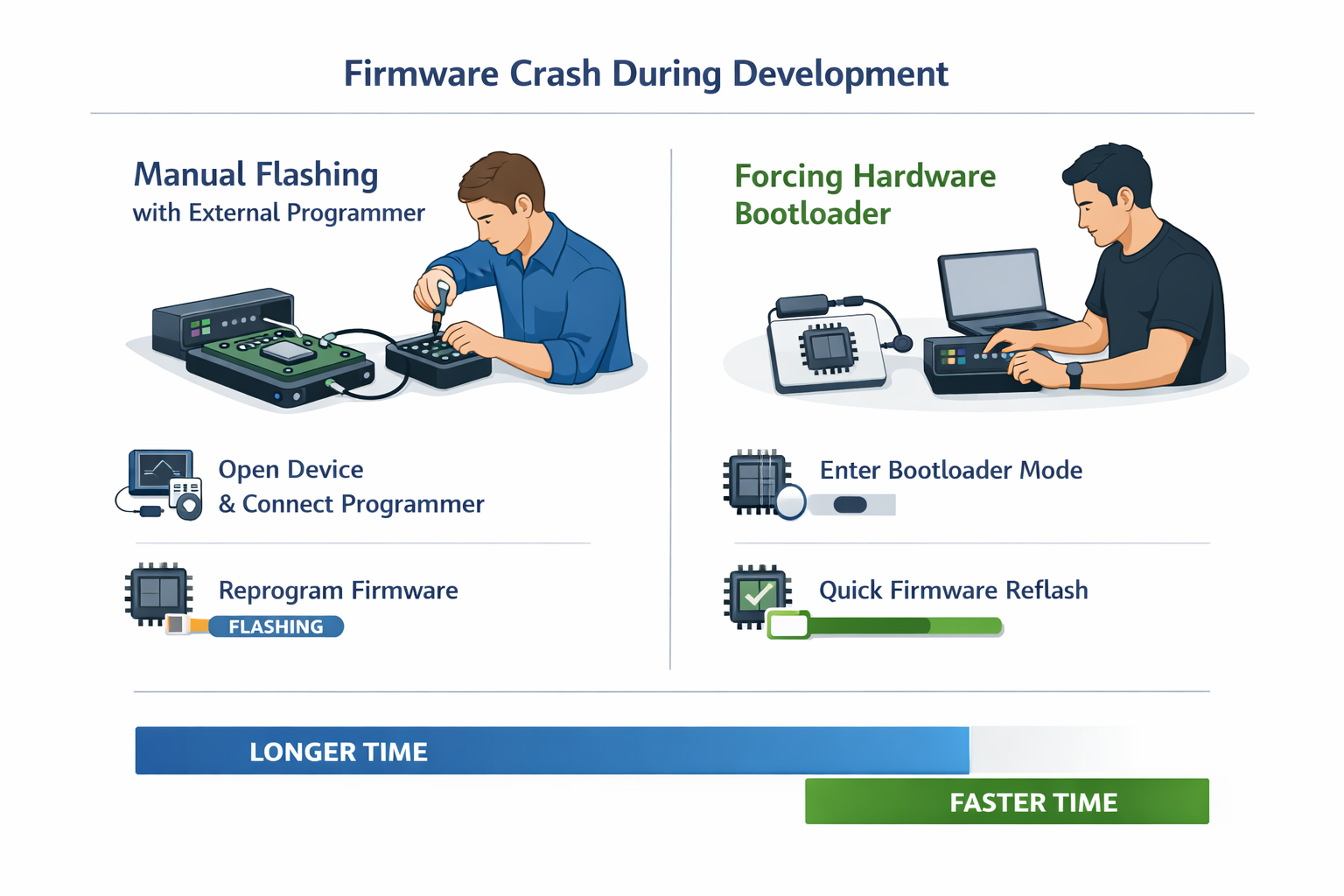

Development Velocity Gains

During development, firmware corruption is common.

Without resilient hardware:

- Engineers lose time manually reprogramming boards.

- Debug cycles slow down.

- Bring-up becomes fragile.

With deterministic recovery:

- Corrupted firmware is routine, not catastrophic.

- Engineers recover boards in seconds.

- Iteration speed increases.

Measured effect:

- Up to 25–40% reduction in average debug turnaround time.

- Fewer boards marked “damaged” prematurely.

- Higher confidence during experimental firmware work.

These compounds across the life of a product.

The Metric Summary

Compared to current-state designs that do not prioritise recovery:

A board designed for guaranteed reflashing demonstrates:

- 80–90% reduction in firmware-related RMAs

- 60–80% reduction in unrecoverable corrupted states

- 20–30% faster production flashing throughput

- 25–40% faster development recovery cycles

- Near-elimination of permanent bricking from interrupted updates

These are measurable, not theoretical improvements.

Recovery Is a Performance Feature

Performance is often measured in MHz and bandwidth.

But lifecycle performance includes:

- Recovery time

- Uptime percentage

- Production throughput

- Debug velocity

- Fleet reliability

A board that can always be reflashed, even when it appears dead, maintains operational continuity.

At Hoomanely, we treat recoverability as part of system architecture — not as an afterthought.

Because a device that cannot be recovered is not just unreliable.

It is slow — in production, in service, and in the field.