LittleFS Tail-Latency for Burst Writes: Commit + Prealloc

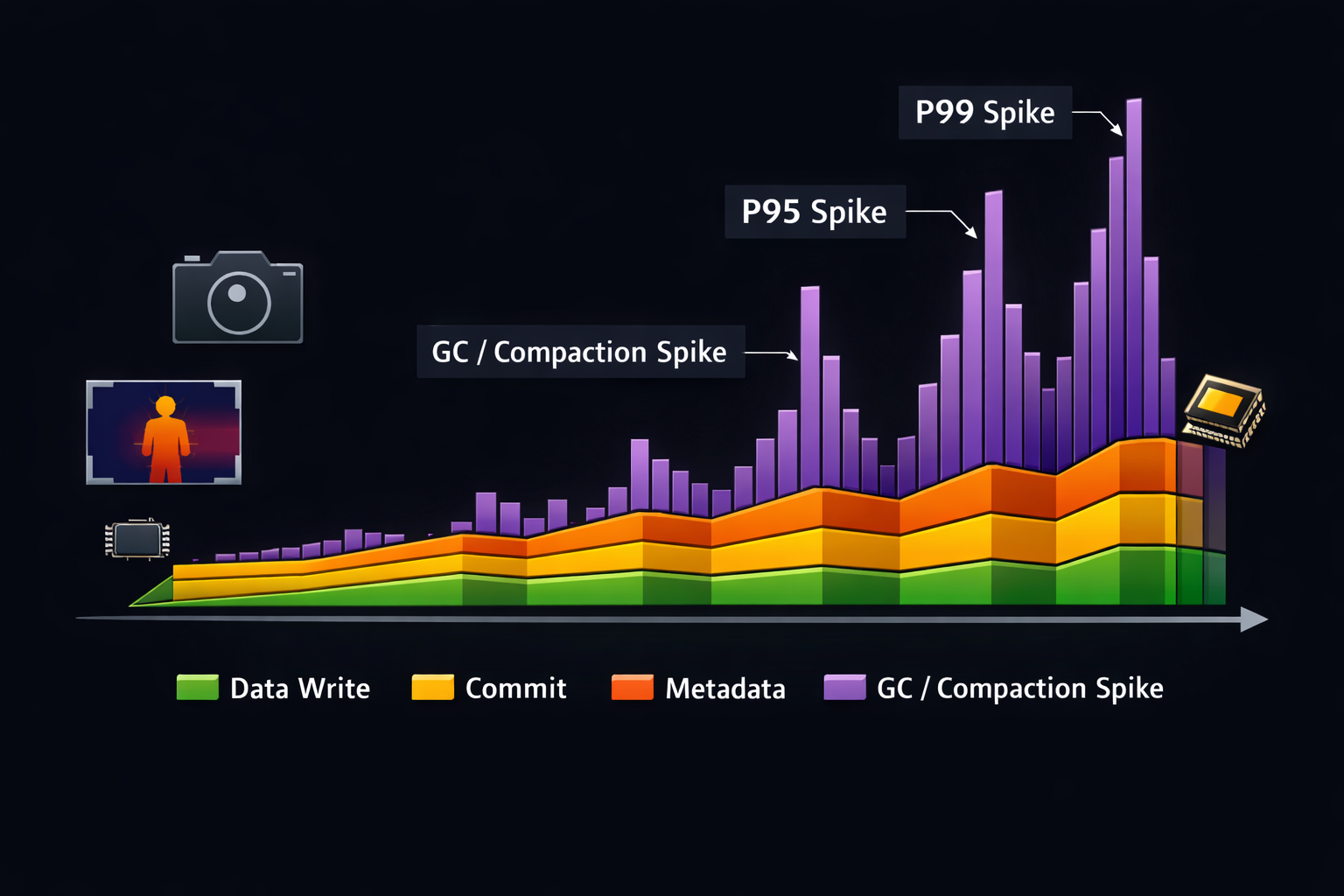

When you first validate a bursty image pipeline on LittleFS, it often looks great: average write times are low, and short tests feel “done.” Then you run a 6–12 hour soak, the flash creeps toward full, and suddenly P95/P99 write latency starts spiking. Frames arrive in bursts, your producer thread blocks longer than expected, and the rest of the system starts paying the price—sensor scheduling jitter, CAN/USB backpressure, dropped frames, and even watchdog risk.

This post is a practical firmware playbook for reducing that long-tail latency without replacing your storage pipeline. The key is to stop treating “write time” as one number and instead make the system explain itself: how much time is spent pushing bytes versus updating metadata, and when garbage collection or compaction quietly steals your latency budget as the device ages and free space shrinks.

From there, we apply two small patterns that change stability dramatically. A commit marker makes each image set “publishable” only when it’s fully persisted (and remains safe under power loss), and best-effort preallocation reduces allocation churn so burst writes don’t repeatedly trigger worst-case GC behavior. The result is a storage path that stays predictably fast—even when the flash is hot, fragmented, and nearly full.

The Problem

LittleFS is designed for embedded flash realities (wear leveling, power-loss resilience, log-structured behavior). That design can create a common tail-latency failure mode for burst workloads:

- Bursty producers create many short-lived files (or frequently new extents).

- As the filesystem fills, allocation becomes harder, and internal cleaning/compaction becomes more frequent.

- Metadata operations (directory updates, rename, close, sync) can suddenly take much longer than the data write itself.

- The result: average throughput looks fine, but the tail is unpredictable.

In image pipelines (camera + thermal frames + metadata sidecars), the important performance truth is: Your system doesn’t fail on averages. It fails when the worst 1–5% of writes stall the whole pipeline.

Approach

We’ll take an incremental approach that is safe, measurable, and compatible with existing pipelines:

Measure what matters (and separate it)

Track timing for:

- Data write time (payload bytes)

- Metadata time (open/close, directory operations, rename)

- Sync time (if you explicitly

fsync/sync) - GC/compaction signal (inferred from long metadata time, or from block-device counters)

Commit marker pattern for “set correctness”

Write image sets in a way that downstream readers never see partial sets—especially after power loss:

- Rename-based commit (

.tmp→ final) or - Footer-based commit (write a verified footer last)

Best-effort preallocation to reduce churn

Avoid repeated allocation under pressure:

- Keep a small file pool (reused slots)

- Or reserve a write budget (space discipline)

- Or use “pre-created empty containers” that you fill and commit

None of this requires changing LittleFS internals. It’s firmware-level engineering around tail behavior.

Process

Step 1: Add instrumentation that isolates tail spikes

If you only time the whole “write set” call, you’ll miss the real source of stalls. Instead, segment your write path into phases that map to filesystem work.

What to measure

For each image set:

t_open_ust_write_us(sum of payload writes)t_close_ust_commit_us(rename or footer finalization)t_total_us

Also record:

fs_used_pct(estimated)set_size_bytes- “mode” (empty FS vs partially full vs near full)

Two metrics that keep you honest

- P99 set commit latency (ms)

- Sustained sets/min after 6 hours (sets/min)

That’s enough to validate stability without turning your post into a dashboard.

Implementation sketch (minimal overhead)

typedef struct {

uint32_t open_us, write_us, close_us, commit_us, total_us;

uint32_t bytes;

uint16_t fs_used_pct;

} write_trace_t;

static inline uint32_t now_us(void);

#define TRACE_START(var) uint32_t var##_t0 = now_us()

#define TRACE_END(var, out) do { (out) += (now_us() - var##_t0); } while(0)

Use it like:

write_trace_t tr = {0};

TRACE_START(total);

TRACE_START(open);

lfs_file_open(&lfs, &f, path_tmp, LFS_O_WRONLY | LFS_O_CREAT | LFS_O_TRUNC);

TRACE_END(open, tr.open_us);

TRACE_START(write);

lfs_file_write(&lfs, &f, buf, len);

TRACE_END(write, tr.write_us);

TRACE_START(close);

lfs_file_close(&lfs, &f);

TRACE_END(close, tr.close_us);

// commit marker step (rename or footer verify)

TRACE_START(commit);

commit_file(path_tmp, path_final);

TRACE_END(commit, tr.commit_us);

TRACE_END(total, tr.total_us);

How to estimate “fill level”

If you already track blocks used at the block-device layer, use that. Otherwise:

- approximate from

lfs_fs_size()(if available in your integration) and your configured block count - or maintain a coarse allocator watermark in your own storage service

You don’t need perfect accuracy—just enough to correlate spikes with “near full.”

Step 2: Use a commit marker so readers never see partial sets

Even if you optimize latency, you still need correctness: readers should only consume complete image sets. Tail latency and correctness are tied—if your pipeline retries or the device reboots mid-burst, you don’t want partially written files to be interpreted as “real data.”

Two patterns work well in LittleFS-based systems:

Option A: Rename-based commit

Write everything to a temporary name, then rename to final name when complete:

set_1234.tmp/- commit →

set_1234/(orset_1234.donemarker)

Why rename works

Renames are typically metadata operations that LittleFS handles in a power-loss-safe way. The key benefit is semantic: downstream readers only scan final names.

Practical structure

- Write image payload files to a temp directory:

sets/set_1234.tmp/cam.bin,sets/set_1234.tmp/therm.bin,sets/set_1234.tmp/meta.json - After all closes succeed, commit:

rename directoryset_1234.tmp→set_1234 - Optionally create a

COMMITfile inside final dir for easy scanning.

Reader rule

- Ignore

.tmpdirectories entirely - Only process

set_*(final) - If you see

set_*but missing expected files, treat as corrupted and quarantine.

Commit function sketch

int commit_dir(const char* tmp, const char* final) {

// Ensure all files are closed before this point.

// Rename is your atomic-ish "publish" step.

int rc = lfs_rename(&lfs, tmp, final);

return rc;

}

Option B: Footer-based commit

If rename/dir operations are your tail spikes, you can avoid rename and instead make the file self-validating:

- Append a fixed footer at the end:

{magic, version, length, crc32} - Only consider the set valid if footer exists and verifies.

This works well when you write a single “container file” per set:

set_1234.bincontains camera + thermal + metadata + footer- The footer is written last; if power is lost, verification fails and the reader skips it.

Footer layout example

magic = 0x53455421(“SET!”)payload_lencrc32(payload)

Reader rule

- Scan file, read footer, verify CRC, then consume.

- If invalid footer, skip.

In image-heavy products like EverBowl, commit semantics are what let downstream transfer/analytics stay simple: readers never need “partial write heuristics.” The pipeline can treat storage as a sequence of published sets, even across reboots.

Step 3: Best-effort preallocation to reduce allocation churn

Now we attack the main source of tail spikes in long runs: allocation/compaction pressure.

You don’t need perfect preallocation. You need enough to avoid “panic allocation” under near-full conditions.

Strategy 1: Reusable file pool (most practical)

Instead of creating brand-new filenames forever, create a bounded pool and reuse slots.

Example:

- Pool of N set containers:

slot_0000 … slot_0255 - A small index file maps

sequence_id -> slot_id - Each slot is overwritten in a controlled way (like a ring buffer)

Why it helps

- Fewer directory entries changing over time

- Less allocation churn

- Predictable metadata patterns

- GC pressure becomes smoother

Implementation idea

- Pre-create the slot files once (at format time or first boot)

- On each set, pick next slot, write there, commit with footer (or rename within slot namespace)

Strategy 2: Reserved space discipline (simple and effective)

Tail spikes get brutal when you’re writing into the last few percent of free space.

Introduce a rule:

- Maintain X% reserved free (e.g., 5–10%)

- If below reserve, switch to “degraded mode”:

- drop optional frames

- reduce burst depth

- prioritize commit markers

- or pause writes until upload/transfer frees space

This is not “giving up.” It’s enforcing predictability. Stable systems protect their future self.

Strategy 3: Pre-created directories for burst batches

If your burst writes create many directories, pre-create a limited number of batch directories:

batch_00 … batch_15

Write sets into current batch until it’s “sealed,” then rotate.

This reduces directory-create bursts at the worst times.

Implementation detail: “best-effort” means you never block forever

The whole point of preallocation is to smooth tail latency, so it can’t be allowed to become a new source of stalls. In other words, preallocation is an optimization path, not a dependency. Your write pipeline must still make forward progress even when the filesystem is under pressure, the pool is fragmented, or a slot can’t be claimed quickly.

Treat preallocation like a bounded fast-path:

- Attempt to allocate / pick a slot quickly using a strict time budget (or a small bounded retry count). If the pool is healthy, this stays cheap and predictable.

- If it fails, immediately fall back to the normal write path (create/allocate as usual). You may take a latency hit in that case, but the system remains correct and doesn’t deadlock or starve the producer.

- Record a metric whenever the fast-path misses—for example

prealloc_hit_rate,prealloc_fallback_count, and optionallyfallback_reason(no free slot, slot busy, reserve threshold reached). This turns “it felt slower today” into an actionable signal: you can tell whether the pool is undersized, whether cleanup is lagging, or whether you’re routinely operating too close to full.

In production pipelines where image sets are uploaded off-device (e.g., for ML validation or post-processing), preallocation makes the on-device behavior boringly consistent during long soak runs—exactly what you want when devices are deployed in homes and you can’t babysit flash state.

Results: How you validate improvements without vanity benchmarks

This is where teams often get stuck: they run a 2-minute test, declare victory, and ship. Tail latency requires a different validation style.

Soak test setup (repeatable and meaningful)

Run a long-duration write test that matches your real burst pattern:

- Same set size distribution (camera + thermal + metadata)

- Same burst cadence (e.g., 3 FPS bursts, then idle)

- Same downstream interactions (if your reader scans storage)

Test at three fill levels:

- Freshly formatted

- Mid-fill (50–70%)

- Near full (85–95%)

What you should expect after these changes

- Commit correctness becomes deterministic (reader never sees partial sets).

- P99 commit latency becomes much tighter, especially near full.

- Overall throughput may remain similar, but the system becomes stable under stress.

If you want one clean target to track:

- Improve P99 set commit latency by 3–5× under near-full conditions (typical outcome when allocation churn is the real culprit).

(Exact numbers depend on block size, wear level, and your burst size, but “multi-x tail improvement” is common when you stop fighting the allocator at the worst time.)

Common issues and how to avoid them

Rename is expensive on my device

Use footer commit with container files, or reduce rename frequency by committing per batch instead of per file.

My reader still sees weird artifacts

Enforce strict reader rules:

- Only read published names OR verified footers

- Quarantine invalid sets

- Run a lightweight cleanup task that deletes

.tmpartifacts on boot

Preallocation made it worse

That usually means:

- You preallocated too aggressively (causing a big upfront stall)

- Or your pool is too large and increases metadata load

Fix:

- Start small (e.g., pool size that covers 2–5 minutes of worst-case burst)

- Grow only if your traces show you need it

We can’t afford sync latency

Don’t sync after every write unless you must. Instead:

- rely on commit markers for correctness

- group sync at safe points (end of burst, or periodic)

Correctness should come from commit semantics—not from “sync everything all the time.”

Key Takeaways

- Tail latency is usually metadata + allocation + GC, not raw data writes.

- Start by instrumenting phases so you can see what’s actually spiking.

- Use a commit marker (rename-based or footer-based) so readers never consume partial sets—even after power loss.

- Apply best-effort preallocation (slot pools + reserved free space) to reduce churn and smooth long-run behavior.

- Validate with soak tests at near-full conditions and track one or two real metrics (like P99 commit latency + sustained sets/min).