From Noisy Clips to Trustworthy Labels: How We Fixed Audio Classification at the Source

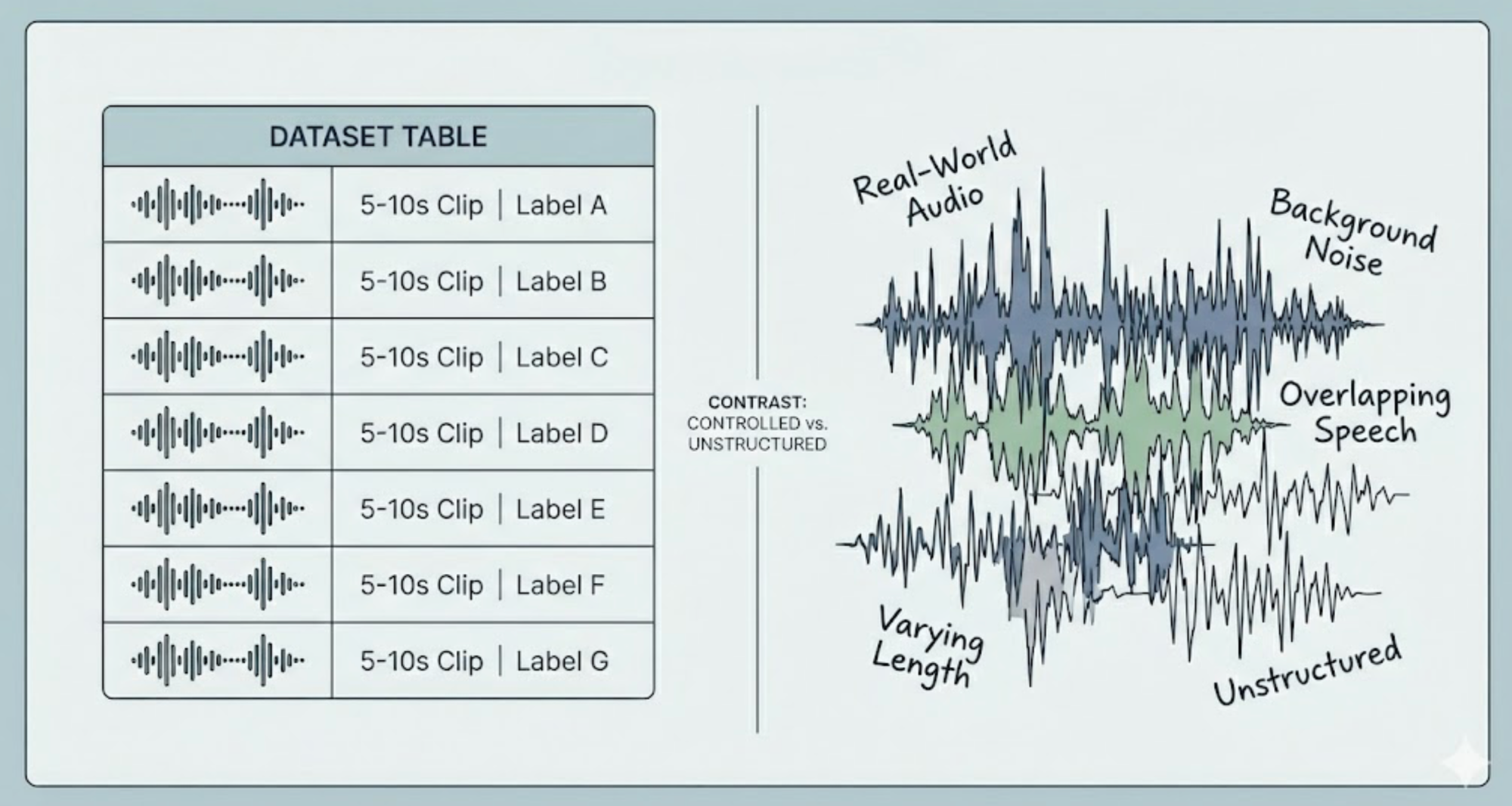

Most public audio datasets look clean on paper.

Five seconds. Ten seconds. One label per clip.

That assumption is exactly where our problems started.

The Hidden Problem With Scraped Audio Datasets

We started with the usual approach: scrape audio clips from public sources, bucket them by class (bark, howl, cough, sneeze, drinking, eating), and train a classifier.

On the surface, everything looked standard:

- Clips were short (5–10 seconds)

- Each clip had a single label

- Class balance looked acceptable

But once we deployed the model, things fell apart.

False positives spiked.

Predictions felt random.

And worst of all—the model seemed confidently wrong.

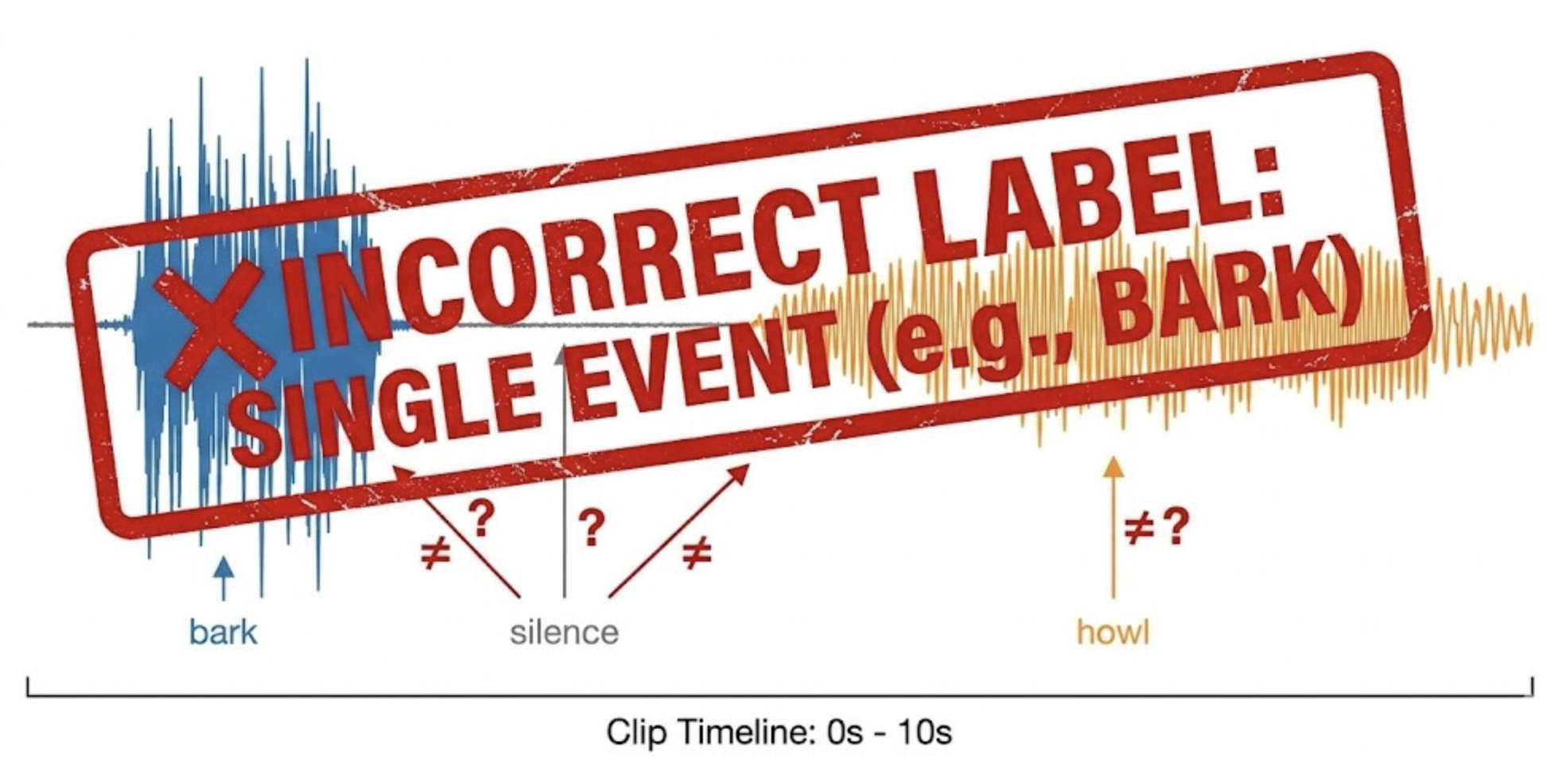

Why “Short Clips” Still Contain Multiple Classes

When we manually listened to the data, the issue became obvious.

A single 10‑second clip often contained:

- Bark → silence → howl

- Chewing sounds mixed with bowl movement

- Environmental noise masking the actual event

Yet the entire clip was labeled as one class.

From the model’s perspective, we were effectively telling it:

“This entire soundscape is a bark.”

The result? Feature contamination.

The model didn’t learn what a bark is—it learned everything that happened around a bark.

The Hallucination Effect in Audio Models

This is where hallucination crept in.

Because multiple sound events coexisted inside a single labeled window:

- Bark features leaked into howl embeddings

- Background noise became class‑defining

- Silence itself started triggering predictions

During inference, the model would confidently predict a class—even when the defining sound wasn’t present.

Not because the model was bad.

But because our labels were lying.

Why More Data Didn’t Fix It

Our first instinct was the obvious one: add more data.

We scraped more clips.

We increased class counts.

We retrained.

Performance got worse.

More data simply amplified the same labeling error at scale.

At that point, it was clear: this wasn’t a model problem—it was a data problem.

Rethinking Audio Labels as Time Ranges

The breakthrough came from a simple realization:

Audio events are temporal.

Labels should be too.

Instead of treating a clip as:

[ 0s -------------------- 10s ] = bark

We needed:

[ 1.2s ---- 2.8s ] = bark

[ 6.1s ---- 8.4s ] = howl

Same audio.

Two clean training samples.

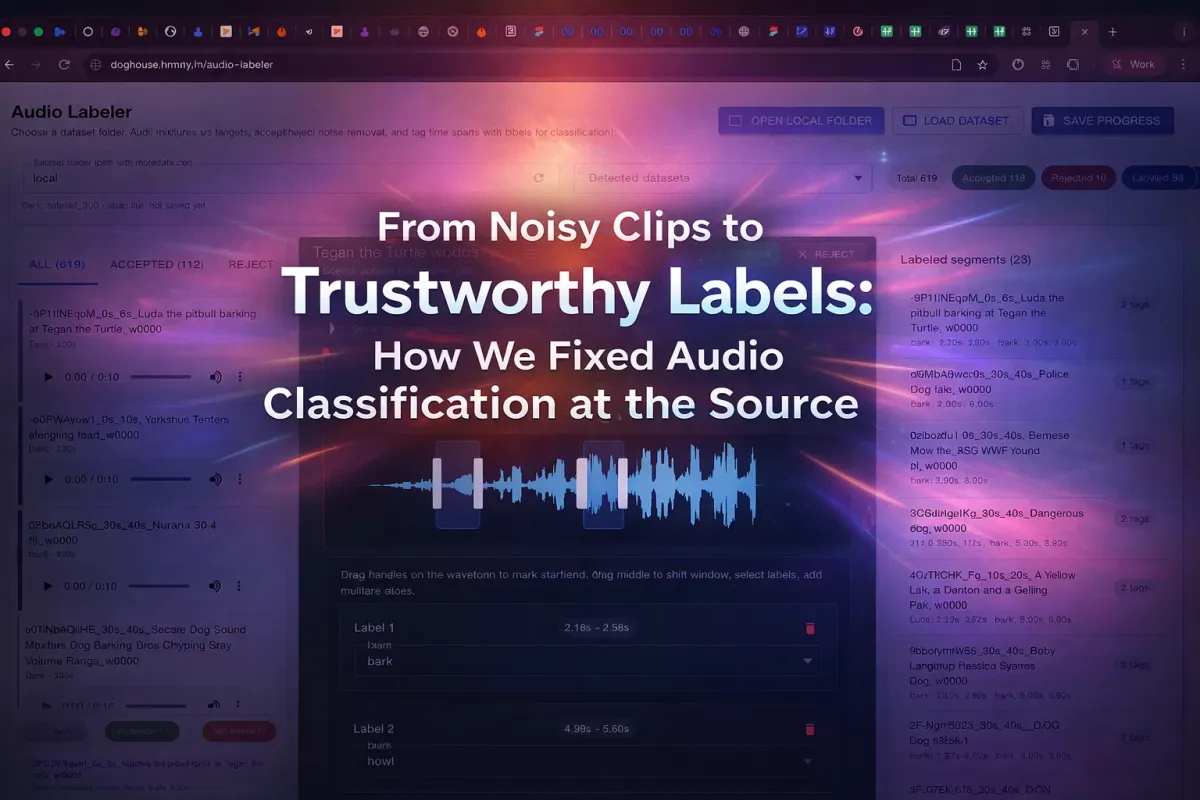

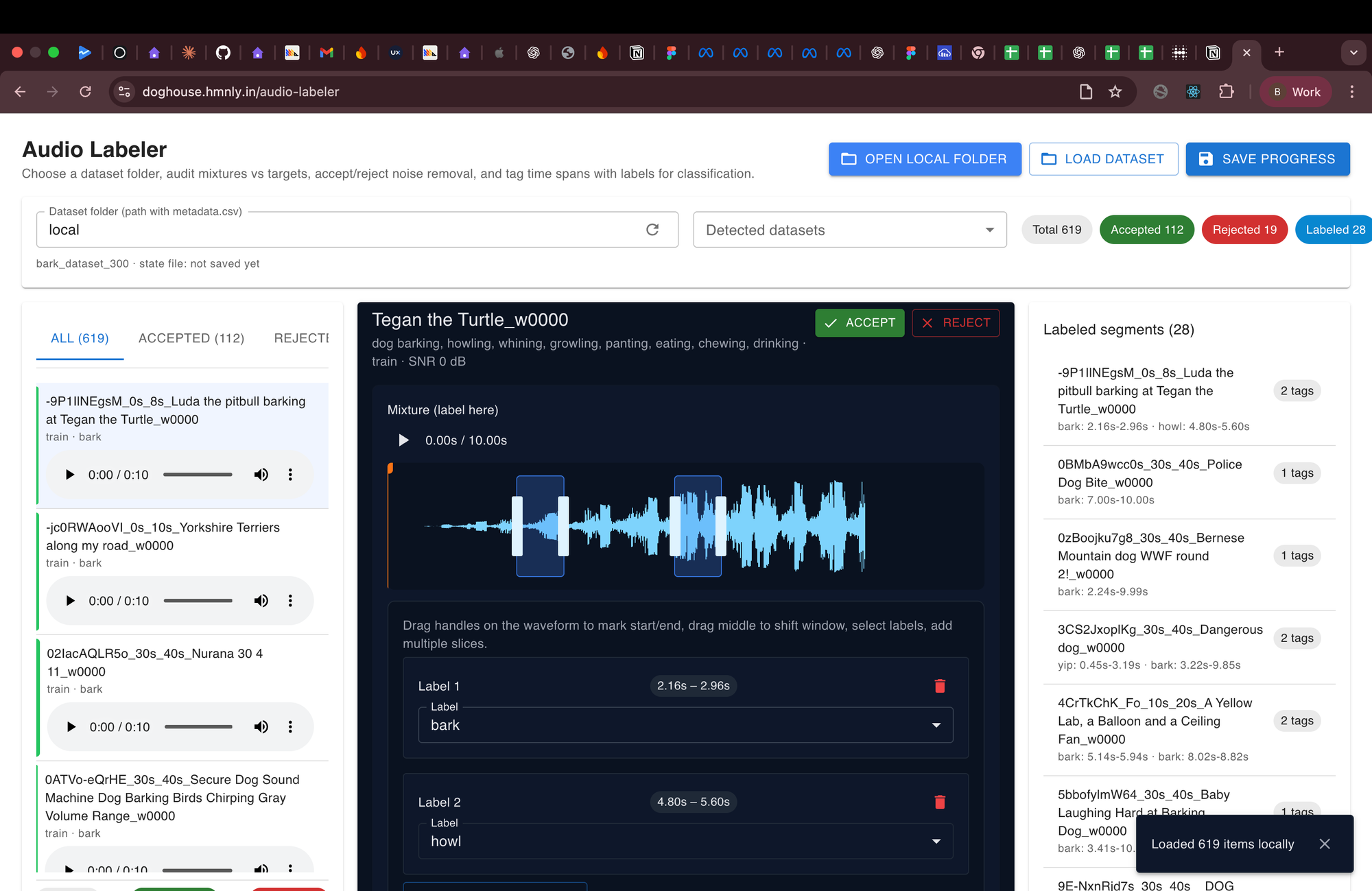

Building Our Own Audio Labeler

So we built an internal audio labeling tool.

Key design decisions:

- Any labeler can play an audio clip

- Select start and end timestamps using a slider

- Assign a class to only that segment

- Export segmented clips automatically

One messy 10‑second clip could now generate:

- Multiple clean samples

- Zero ambiguity about what sound belongs to which class

Turning Noise Into Data

This flipped our dataset economics completely.

Before:

- One clip → one unreliable label

- Multi‑class audio → discarded or mislabeled

After:

- One clip → multiple high‑quality samples

- Overlapping sounds → usable data

We didn’t just clean the dataset.

We expanded it—without scraping anything new.

What Changed in Model Performance

After retraining with segmented audio:

- False positives dropped significantly

- Bark vs howl confusion reduced

- Model confidence aligned with actual sound presence

Most importantly, predictions became explainable by listening.

If the model predicted a bark, you could hear the bark in that exact time window.

That’s a rare feeling in audio ML.

The Real Lesson: Labeling Is Part of the Model

We tend to treat labeling as a preprocessing step.

In reality, it defines what the model can learn.

If your labels ignore time,

your model will hallucinate meaning where none exists.

Sometimes the biggest model improvement doesn’t come from a new architecture—but from admitting that your labels were wrong.