Bounded by Design: Preventing Cascading Failures

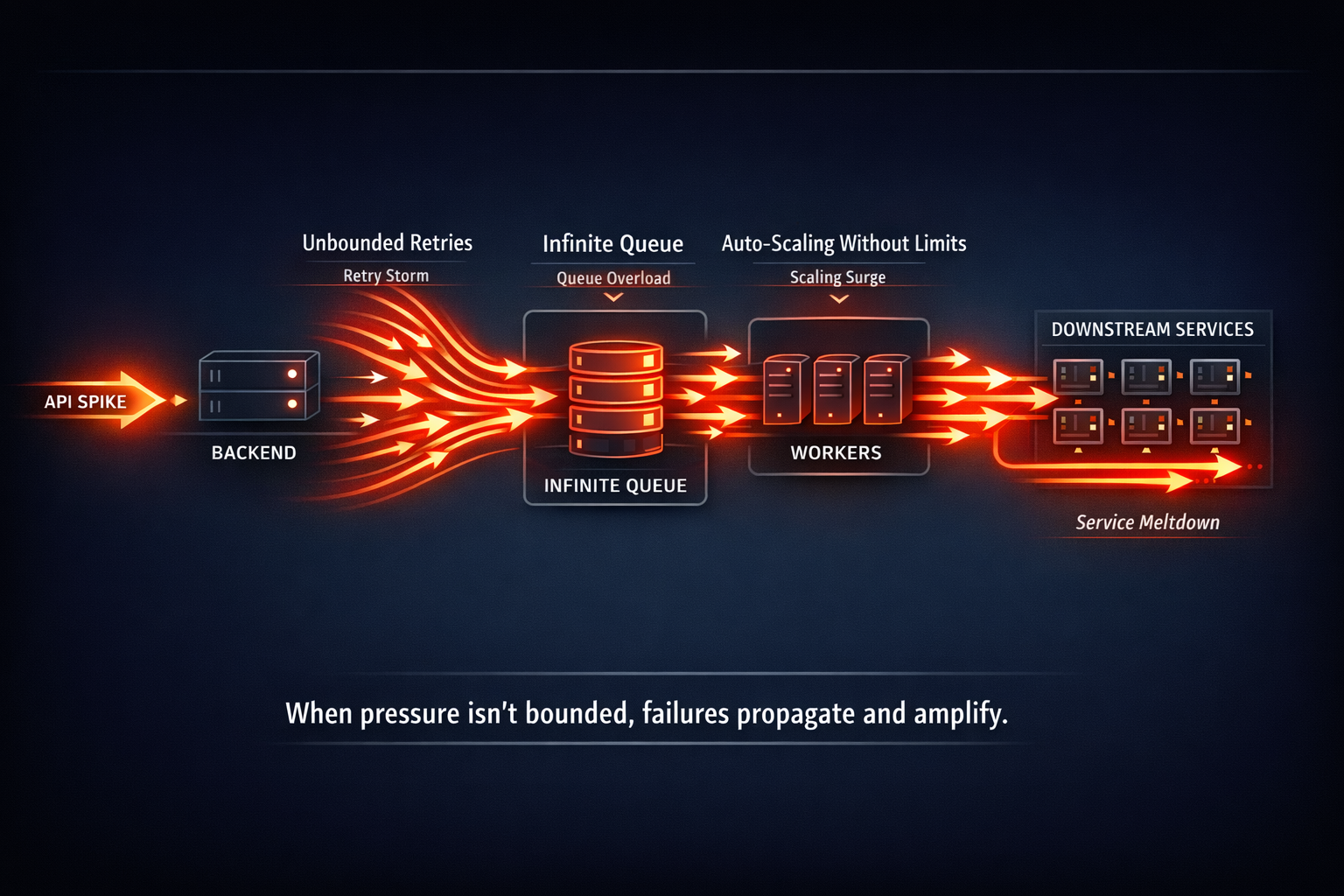

Modern backend systems rarely fail because of a single line of bad code. More often, instability emerges when pressure moves through the system without clear boundaries. A sudden API spike increases retries, retries consume worker capacity, workers enqueue faster than downstream services can process, and queues quietly accumulate risk. Latency rises, costs follow, and by the time alerts trigger, the system is already operating outside safe limits. This chain reaction is a familiar reality for teams running production systems under real-world load.

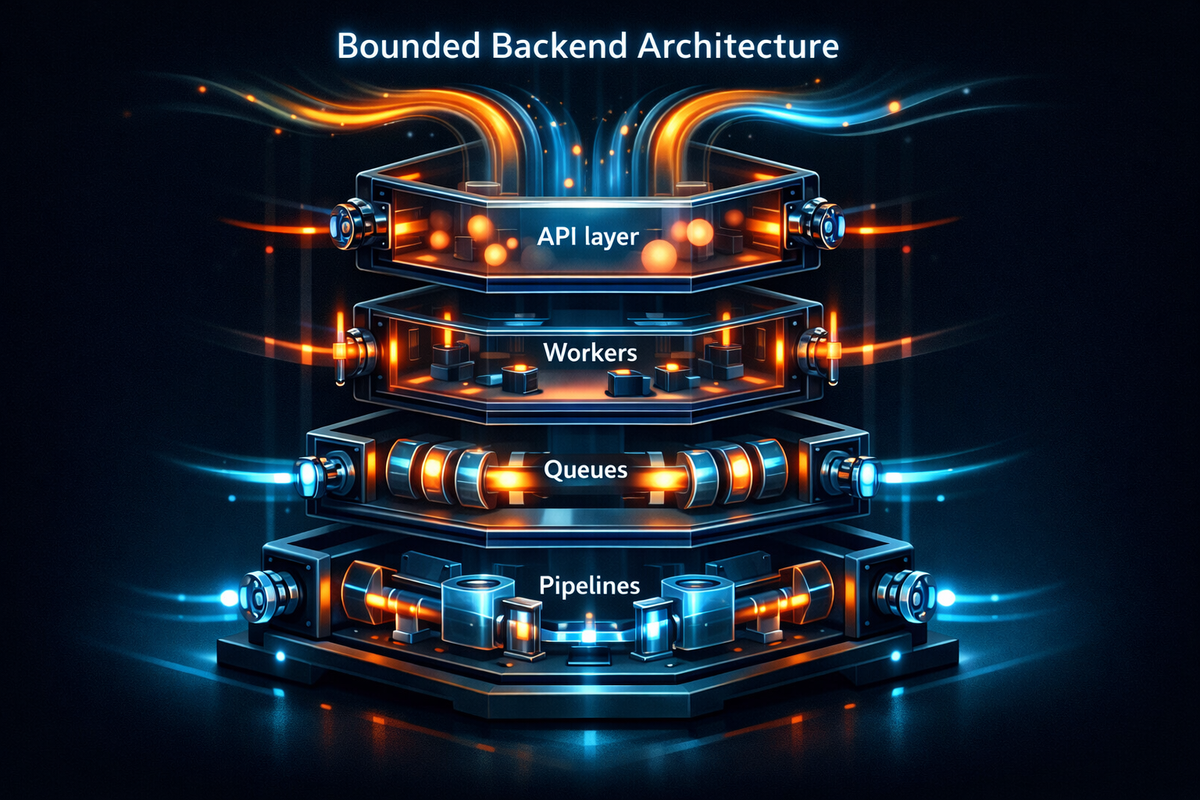

At Hoomanely, reliability is treated as an architectural property—not something achieved by scaling endlessly or reacting faster during incidents. Stable systems are designed with intention: every layer has clearly defined limits, every interaction has a bounded impact, and every component knows how much pressure it is allowed to pass downstream. This approach ensures that growth, spikes, and partial failures remain contained rather than amplified.

This post explores how boundedness becomes a first-class design principle across APIs, background workers, and asynchronous pipelines—showing how explicit constraints transform unpredictable load into controlled, resilient behavior across the entire backend architecture.

The Core Idea: Cascading Failures Are a Design Smell

Cascading failures don’t appear suddenly. They emerge when a system allows unbounded behavior at critical boundaries:

- APIs that accept unlimited concurrent requests

- Workers that scale without backpressure

- Queues that grow indefinitely

- Retries that amplify load instead of healing it

- Fan-out pipelines that multiply work without limits

Individually, each component looks reasonable. Collectively, they create a system where every failure makes the next failure worse.

Bounded design flips this dynamic. Instead of asking “How much can this handle?”, it asks:

“What is the maximum pressure this component is allowed to exert on the rest of the system?”

When every layer answers that question explicitly, cascading failures lose their fuel.

Bounded APIs: Containing Pressure at the Edge

APIs are the most dangerous place to be unbounded. They are directly exposed to users, devices, integrations, and sometimes the public internet. Any unbounded behavior here becomes everyone else’s problem.

What Goes Wrong Without Bounds

- Unlimited concurrent requests exhaust compute

- Slow downstream calls hold connections open

- Client retries pile onto already failing endpoints

- Load balancers amplify spikes instead of smoothing them

Designing APIs That Fail Predictably

Key bounded patterns we apply:

- Concurrency caps at the API layer

Requests beyond a threshold are rejected fast, not queued indefinitely. - Time-bounded execution

APIs have strict deadlines. If work can’t finish in time, it doesn’t start. - Explicit degradation paths

Partial responses or cached fallbacks are preferred over blocking. - Backpressure-aware clients

Clients are encouraged (and sometimes forced) to respect retry-after semantics.

The result is counterintuitive but powerful: during spikes, error rates may increase—but system health remains stable.

Bounded Workers: Scaling Isn’t a Safety Net

Background workers are often treated as the shock absorbers of backend systems. “Just throw it into a queue,” the thinking goes. “Workers will catch up.”

That logic only holds if workers themselves are bounded.

The Worker Trap

Unbounded worker pools introduce hidden risks:

- Auto-scaling creates downstream overload

- Slow jobs block fast ones

- Retries stack on top of in-flight work

- Memory and file descriptors exhaust quietly

When workers scale without limits, they stop being a buffer and become an amplifier.

Here’s a clean, senior-level rewrite that keeps the technical meaning intact, removes over-bulletin usage, and reads like a confident architectural deep dive.

Designing Workers With Explicit Limits

Bounded workers behave more like valves than vacuums. Their purpose is not to absorb unlimited work, but to regulate how much pressure is allowed to pass through the system at any given time. At Hoomanely, worker design prioritizes controlled throughput over maximum throughput, because unconstrained workers are one of the fastest ways to trigger cascading failures.

Each worker group operates with explicit, fixed concurrency limits. Scaling is intentional and measured, not a reaction to transient spikes. This prevents sudden load surges from overwhelming downstream dependencies such as databases, external services, or enrichment pipelines. When demand exceeds capacity, work is not silently queued forever—it is intentionally constrained.

Every work item is also evaluated against a time budget. Jobs that cannot complete within a defined execution window are either deferred or dropped, rather than being allowed to consume resources indefinitely. This ensures that workers remain responsive and prevents long-running tasks from monopolizing execution slots.

To avoid head-of-line blocking, workloads are segmented by execution profile. Fast, lightweight tasks are isolated from slower or more expensive paths using separate queues or worker pools. This guarantees that a few slow jobs cannot stall an entire processing pipeline.

Finally, workers adopt fail-fast semantics. If a worker determines that it cannot safely execute a task—due to load, time constraints, or downstream pressure—it rejects the work immediately instead of attempting a best-effort execution. This early rejection is a deliberate design choice: it protects system stability by preventing overload from propagating further.

Together, these constraints ensure that worker pools act as protective boundaries, absorbing pressure in a controlled manner and shielding downstream systems from overload, rather than amplifying it.

Queues: Buffers, Not Bottomless Pits

Queues are deceptively dangerous. They hide problems until they don’t.

An unbounded queue looks healthy when traffic spikes. Messages are accepted, latency remains low, and dashboards stay green—until processing falls behind. Then recovery becomes exponentially harder.

Why Unbounded Queues Fail

- Backlogs grow faster than drain rates

- Cost scales invisibly

- Old messages lose relevance

- Downstream systems are hit long after the original spike

Making Queues Explicitly Bounded

Bounded queues force early decisions instead of deferred disasters.

- Maximum queue depth

When full, producers must fail or shed load. - Age-based expiration

Stale work is discarded intentionally. - Priority lanes

Critical signals bypass best-effort tasks. - Observable backlog health

Queue depth is a first-class SLO, not a hidden metric.

In practice, this means accepting that some work will be dropped. The alternative is far worse: letting all work pile up until nothing matters anymore.

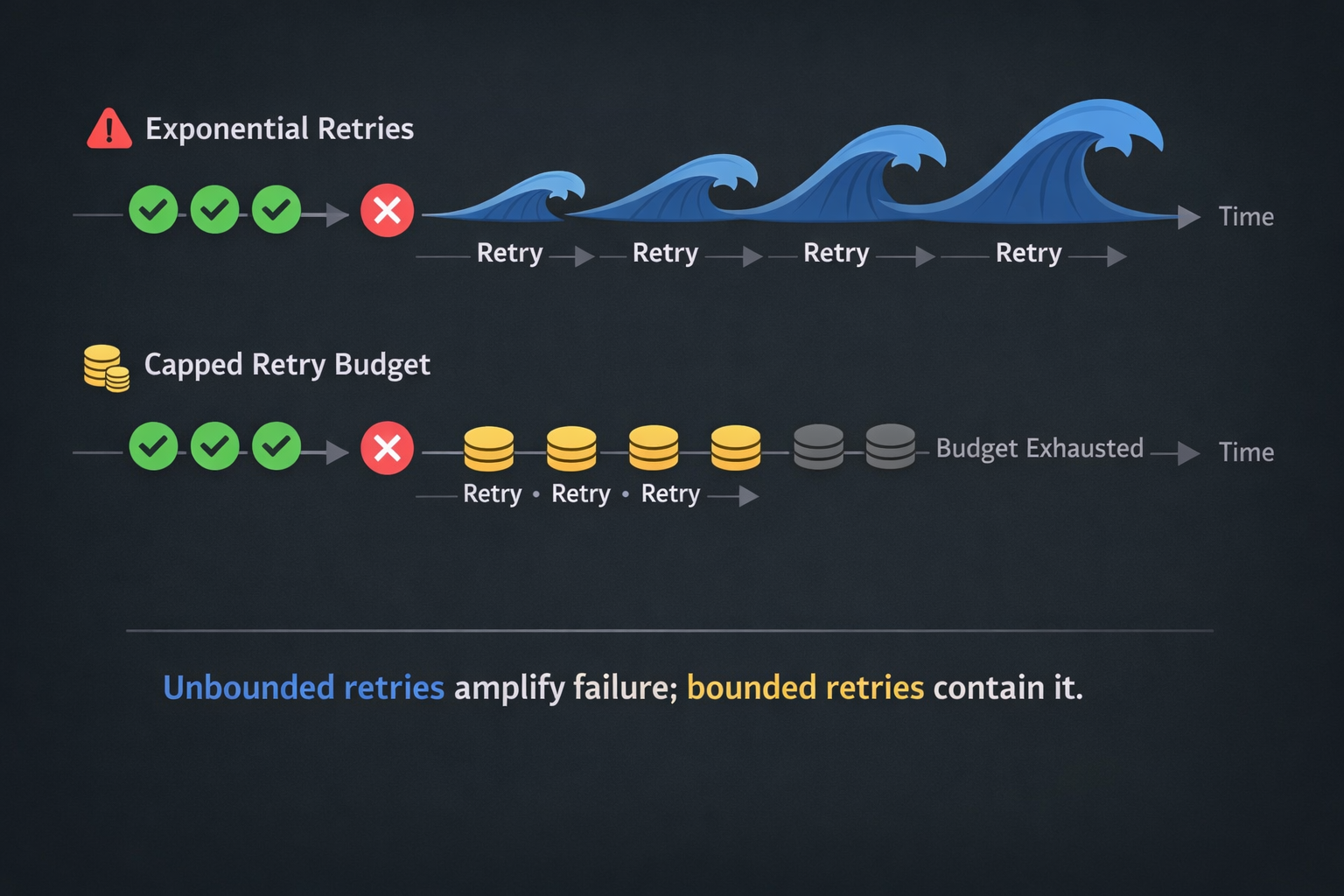

Retries: Healing vs Harmful Amplification

Retries are one of the most common causes of cascading failures. They feel safe. They are not.

The Retry Fallacy

- Failures are transient

- Retrying is cheaper than failing

- The system will eventually recover

Under load, these assumptions collapse. Retries often outnumber original requests, compounding pressure exactly when systems are weakest.

Bounded Retry Strategies

- Retry budgets

Only a small fraction of traffic is allowed to retry. - Exponential backoff with jitter

Prevents retry synchronization. - Retry classification

Only retry errors that are proven transient. - Circuit breakers over retries

Stop sending traffic when recovery is unlikely.

Retries should reduce load, not increase it. If a retry strategy doesn’t explicitly cap its impact, it’s unsafe by default.

Fan-Out Pipelines: Multiplication Is Dangerous

Fan-out pipelines—where one event triggers many downstream actions—are powerful and risky.

A single input event can generate:

- Multiple async jobs

- Multiple database writes

- Multiple notifications

- Multiple ML inferences

Without bounds, fan-out becomes exponential work generation.

Designing Safe Fan-Out

Safe fan-out requires intentional constraints:

- Maximum fan-out limits

Hard caps on downstream actions. - Lazy expansion

Generate work only when needed. - Batching over explosion

Prefer aggregated processing. - Idempotent downstream handlers

Prevent duplicate amplification.

At Hoomanely, fan-out pipelines are treated as cost multipliers, not free abstractions. Every additional branch is justified, measured, and bounded.

Hoomanely builds systems that interact with physical devices, mobile apps, and cloud services—often simultaneously. This makes boundedness non-negotiable.

- Device ingestion APIs enforce strict concurrency and time limits.

- Background processing pipelines cap fan-out when analyzing sensor events.

- Retry budgets prevent device reconnect storms from overwhelming cloud services.

In some cases—such as handling bursts from EverSense or EverBowl devices—bounded design allows us to shed non-critical processing while preserving core functionality. Users may see delayed insights, but the system remains responsive and trustworthy.

Reliability, here, is not invisibility of failure—but predictable degradation.

Results: What Bounded Systems Buy You

Systems designed with explicit bounds exhibit consistent traits:

- Failures stay localized

- Recovery is fast and predictable

- Costs remain controlled under load

- Alerts fire early, not after collapse

- Engineers sleep better during incidents

Most importantly, bounded systems fail honestly. They don’t pretend to handle infinite load. They communicate limits clearly—to clients, operators, and downstream systems.

Takeaways

- Cascading failures emerge from unbounded behavior, not isolated bugs

- Every boundary—API, worker, queue, retry, fan-out—needs explicit limits

- Boundedness is a reliability strategy, not a performance trick

- Dropping work intentionally is safer than processing everything eventually

- Systems that degrade predictably earn long-term trust

At Hoomanely, bounded design is foundational. It’s how we ensure that when the unexpected happens—and it always does—our systems bend without breaking.