Building High-Speed Camera : Mastering MIPI CSI-2 Device

Introduction

Imagine a pet healthcare system that can detect subtle changes in your pet's gait, identify early signs of skin conditions, monitor breathing patterns during sleep, or track behavioral changes that signal discomfort — all through intelligent vision processing happening at the edge. This isn't science fiction. It's the convergence of high-speed embedded imaging, real-time AI inference, and thoughtful systems engineering.

Modern embedded vision platforms demand more than megapixels and frame rates. They require seamless hardware-software integration, deterministic latency for real-time decision-making, power efficiency for always-on monitoring, and robust drivers that never fail in production deployment.

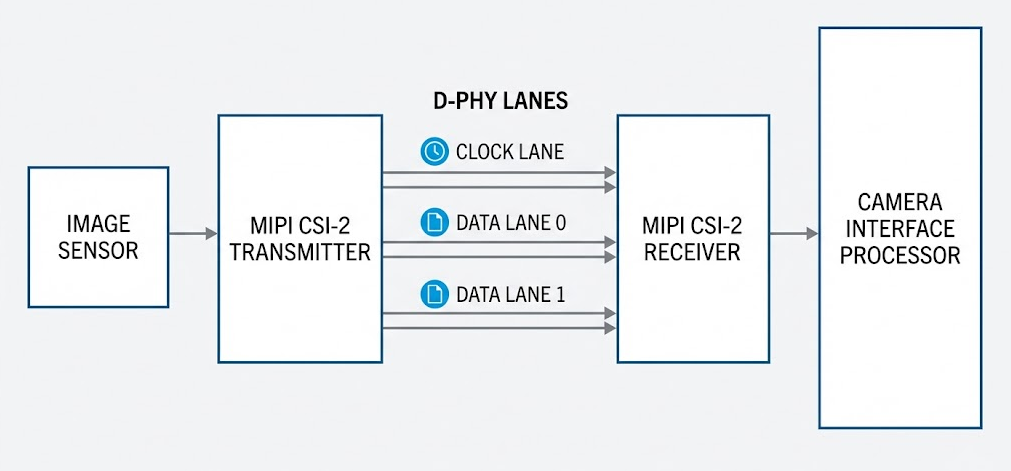

The MIPI CSI-2 interface with D-PHY multi-lane configuration has become the de facto standard for connecting image sensors to application processors, enabling data rates exceeding multiple gigabits per second. But bridging the gap between a raw image sensor and actionable vision intelligence requires deep understanding of physical layer protocols, kernel driver architecture, and the Linux Video4Linux2 framework.

This technical deep dive walks through the complete journey of MIPI CSI-2 device driver development — from understanding hardware interfaces and protocol layers to implementing production-grade Linux kernel modules that power real-world embedded vision applications.

Understanding MIPI CSI-2: Beyond the Marketing Specs

MIPI CSI-2 isn't simply a connector specification — it's a complete ecosystem of physical signaling, protocol layers, and power management states that must work in harmony.

Why CSI-2 Dominates Embedded Vision

Scalable Bandwidth Architecture — The interface scales from single-lane configurations supporting basic imaging to four-lane implementations delivering aggregate throughput exceeding 6 Gbps. Each lane operates independently, with the protocol layer distributing and merging data across available lanes dynamically.

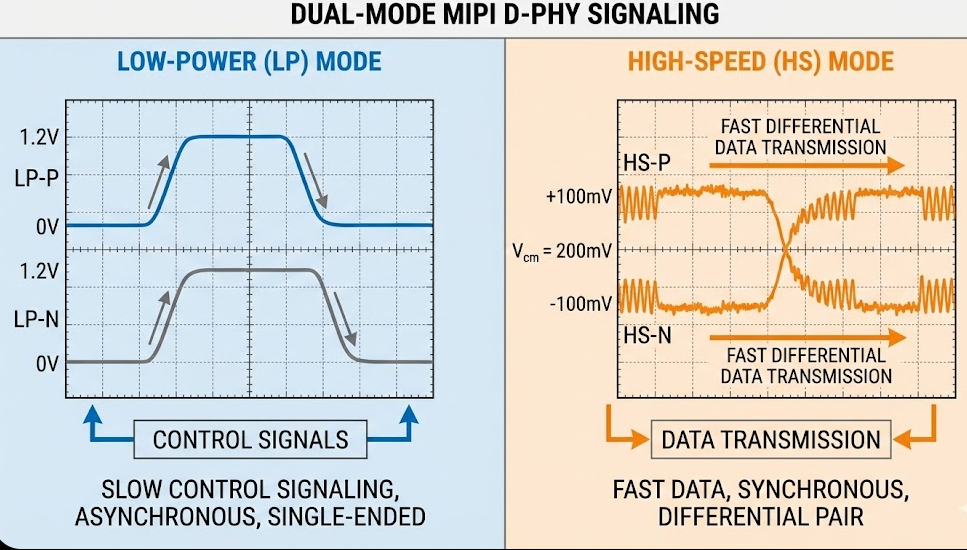

Power-Optimized Signaling — D-PHY physical layer implements dual-mode operation: low-power mode for control and configuration using single-ended signaling, and high-speed mode for data transfer using low-voltage differential signaling that minimizes power consumption while maximizing noise immunity.

Packet-Based Protocol — Unlike older parallel interfaces that require precise timing alignment across multiple signals, CSI-2 uses a self-contained packet structure carrying synchronization, data, and metadata. This simplifies PCB routing and enables longer cable lengths when combined with SerDes technology.

Virtual Channel Support — A single physical interface can multiplex up to 16 virtual channels, enabling multi-camera systems, embedded data streams, or separate image and metadata channels without requiring additional physical connections.

For applications like continuous pet health monitoring where multiple imaging modalities — visible light for behavior analysis, thermal imaging for temperature tracking, and depth sensing for gait analysis — must operate simultaneously, this virtual channel capability becomes essential.

[Visual #1 needed here]

The Physical Layer: Where Silicon Meets Signal

Understanding D-PHY operation separates engineers who can integrate reference designs from those who can debug production issues at 3 AM.

Dual-Mode Signaling Architecture

Low-Power (LP) Mode operates using single-ended signaling at approximately 1.2V amplitude over the differential lines. This mode handles all control functions: lane initialization, mode transitions, escape mode commands, and Ultra-Low Power State (ULPS) entry and exit.

Think of LP mode as the control plane — it establishes communication, negotiates parameters, and manages power states. Data rates remain intentionally low (around 10 Mbps) because the physical signaling uses relatively large voltage swings that would consume excessive power at higher frequencies.

High-Speed (HS) Mode switches to differential signaling with much smaller voltage swings (approximately ±200mV) centered around a common-mode voltage. This enables multi-Gigabit per second data rates while maintaining excellent noise rejection.

The transition between modes isn't instantaneous. The specification defines precise timing parameters — THS-Prepare, THS-Zero, THS-Trail — that determine how long the transmitter must maintain specific voltage levels during mode transitions. Getting these wrong causes synchronization failures that manifest as corrupted frames or stream dropouts.

Lane Management and Synchronization

In multi-lane configurations, data gets distributed across lanes in a round-robin fashion. Lane 0 always exists; lanes 1-3 are optional based on bandwidth requirements. The receiving controller must deserialize data from each lane, perform clock recovery, and merge the byte streams back into coherent packets.

Clock Lane Modes — The clock lane can operate in continuous mode (clock always running) or non-continuous mode (clock starts and stops with data bursts). Continuous mode simplifies receiver design but consumes more power. Non-continuous mode requires more sophisticated clock recovery but enables deeper power-saving states between frames.

Lane Polarity — Each differential pair has positive and negative signals. If PCB routing accidentally swaps these, the D-PHY receiver typically includes polarity detection and correction. However, relying on this feature masks design errors that might cause problems during manufacturing when variations exceed the correction range.

Critical Timing Parameters

Several timing parameters define the electrical behavior of lane transitions:

THS-Prepare — Time the transmitter must hold LP state before transitioning to HS mode. Too short and the receiver misses the transition; too long and latency increases unnecessarily.

THS-Zero — Duration the transmitter holds HS-0 state after THS-Prepare. This provides time for the receiver's clock recovery circuit to lock onto the incoming signal before data transmission begins.

THS-Trail — Time the transmitter must continue driving HS state after the last bit before returning to LP mode. Insufficient trail time causes the receiver to miss the final bits.

These aren't academic specifications — they're debugged with oscilloscopes at 2 GHz bandwidth showing eye diagrams with picosecond resolution. A manufacturing process variation that shifts timing by 100 picoseconds can move your system from "works perfectly" to "fails intermittently."

[Visual #2 needed here]

Protocol Layers: Structuring the Data Pipeline

The CSI-2 specification defines a layered protocol stack that transforms pixel data into transmitted bytes and back.

Application Layer: Your Software's View

At the top sits your application — whether it's a computer vision pipeline analyzing pet behavior, a machine learning model detecting skin anomalies, or a video encoder preparing streams for cloud upload. This layer doesn't concern itself with lanes, packets, or voltage swings. It simply requests frames through APIs like Video4Linux2.

Pixel-to-Byte Conversion

Image sensors generate pixel data in various formats: RAW8 (8 bits per pixel), RAW10 (10 bits per pixel), RAW12, RGB, YUV, and others. The pixel-to-byte layer packs this data efficiently into byte-aligned structures.

For RAW10 format, four pixels consume five bytes: each pixel contributes its 8 most significant bits as one byte, then all four pixels' 2 least significant bits pack into the fifth byte. This maximizes dynamic range while minimizing bandwidth consumption.

The conversion happens transparently, but understanding it matters when debugging why your bandwidth calculations don't match observed throughput — those "extra" bytes from pixel packing add up across millions of pixels.

Low-Level Protocol: Packets and Synchronization

The LLP layer structures data into two packet types:

Short Packets — Header-only packets used for synchronization and control. Frame Start (FS), Frame End (FE), Line Start (LS), and Line End (LE) packets mark frame and line boundaries. These packets include virtual channel ID, data type, and a 16-bit word count or data field.

Long Packets — Carry actual pixel data or embedded metadata. Each long packet includes a header (data type, virtual channel, word count), payload (up to 65535 bytes), and footer (16-bit CRC for error detection).

Frame structure looks like:

Frame Start (short packet)

Line Start (short packet)

Pixel Data (long packet)

Line End (short packet)

... (repeat for each line)

Frame End (short packet)The receiver validates packet structure, checks CRCs, and assembles lines into complete frames. Any packet corruption — detected via CRC mismatch — typically discards the entire frame rather than deliver corrupted data to the application.

Lane Management Layer

This layer distributes outgoing byte streams across available lanes and merges incoming lanes back into a single byte stream. Distribution happens at byte granularity — consecutive bytes alternate lanes in round-robin fashion.

Multi-lane operation isn't just about bandwidth; it's about flexibility. A system supporting four lanes can operate in 1-lane mode (reduced bandwidth, lower power) or 4-lane mode (maximum throughput) without hardware changes. This matters for products with multiple SKUs sharing common silicon but different imaging requirements.

[Visual #3 needed here]

Testing and Validation: From First Light to Production

Bringing up a camera system follows a methodical process.

Initial Hardware Verification

Before attempting streaming:

Clock Signal Verification — Use oscilloscope to verify sensor clock is present and correct frequency. Missing or wrong clock is the #1 cause of "sensor not responding" failures.

I2C Communication — Verify I2C read/write operations. Try reading sensor chip ID register — if this fails, nothing else will work.

GPIO Levels — Confirm reset and power-down GPIOs reach correct logic levels. Don't assume GPIO direction or polarity is correct.

Power Rails — Measure supply voltages with sensor powered on. Verify current consumption matches datasheet typical values.

Real-World Application: Pet Healthcare Vision Systems

At Hoomanely, we're building the world's first complete pet healthcare ecosystem powered by Physical Intelligence — and embedded vision is central to this mission.

Multi-Modal Sensing for Comprehensive Health Monitoring

Our platform integrates multiple imaging modalities:

Behavioral Analysis — High-resolution visible-light imaging captures subtle changes in movement patterns, posture, and activity levels that signal discomfort or illness before other symptoms appear.

Thermal Monitoring — Integrated thermal imaging provides non-contact temperature tracking, detecting fever or localized inflammation that might indicate injury or infection.

Depth Sensing — Time-of-flight or structured light enables precise gait analysis, identifying lameness or coordination issues with millimeter accuracy.

Night Vision — Infrared illumination and sensitivity allow 24/7 monitoring without disturbing your pet's sleep cycles.

All these sensors stream data simultaneously through virtual channels in our MIPI CSI-2 implementation, processed by Edge AI algorithms running on the embedded processor.

Edge AI: Intelligence Where It Matters

Raw pixel data means nothing without intelligent processing. Our Biosense AI Engine analyzes video streams in real-time:

Behavior Recognition — Deep learning models detect normal vs abnormal behaviors: excessive scratching, restlessness, reduced activity, changes in eating patterns.

Posture Analysis — Computer vision algorithms identify subtle changes in how pets stand, walk, or rest — early indicators of joint pain or discomfort.

Breathing Rate Monitoring — Video analysis of chest movement provides continuous respiratory rate without any wearables or physical contact.

Skin Condition Detection — High-resolution imaging combined with ML models can identify hot spots, hair loss, or skin irritations requiring veterinary attention.

This isn't reactive monitoring — it's continuous preventive care that adds quality years to your pet's life.

MIPI CSI-2 with D-PHY provides scalable, power-efficient camera connectivity for embedded vision applications from mobile devices to industrial systems to pet healthcare platforms.

Understanding physical layer operation — LP and HS modes, timing parameters, lane synchronization — is essential for debugging production issues beyond simple integration.

The layered protocol architecture separates concerns: physical signaling, lane management, packet structure, and application interface, enabling modular driver development.

Real-world applications like Hoomanely's pet healthcare platform demonstrate how robust camera integration enables continuous monitoring and preventive care through Edge AI and multi-sensor fusion.