Closing the Loop: How User Feedback Calibrates Our AI

The Calibration Problem Nobody Talks About

When you ship a hardware product with sensors, you inherit a problem that pure software companies never face: the real world is messy.

At Hoomanely, our smart bowl—Everbowl—uses load cells to measure food and water consumption and thermal sensors to track a dog's body temperature. In a lab, these sensors are precise. In someone's kitchen, with a 90-pound Great Dane who slams into the bowl, or a nervous Chihuahua who eats three kibbles at a time, precision becomes relative.

The challenge isn't the sensors themselves. It's that every dog, every bowl placement, and every home environment introduces variance that no factory calibration can anticipate. A model trained on aggregate data will be mostly right for most dogs—but "mostly right" isn't good enough when pet parents are making health decisions based on the numbers we show them.

This post explores how we solved this problem by doing something counterintuitive: we asked the user.

Why Generic Models Fall Short

Everbowl tracks two primary health signals:

- Consumption inference: How much food or water did the dog consume, and over what duration?

- Temperature estimation: What is the dog's approximate body temperature based on thermal readings during feeding?

Both involve translating raw sensor data into meaningful health metrics. And both are surprisingly hard to get right universally.

Consumption inference sounds simple: measure weight before and after. But dogs don't eat cleanly. They push kibble out of the bowl. They splash water. They walk away mid-meal and return later. The "before and after" becomes a noisy time series that requires interpretation.

Temperature estimation is even trickier. A thermal sensor pointed at a feeding dog captures a mix of ambient heat, reflected surfaces, and the dog's actual body. The reading depends on the dog's fur density, the distance to the sensor, and even whether the dog is panting.

We could build increasingly complex models to handle these variances. But there's a simpler insight: the user already knows the ground truth.

The Human-in-the-Loop Approach

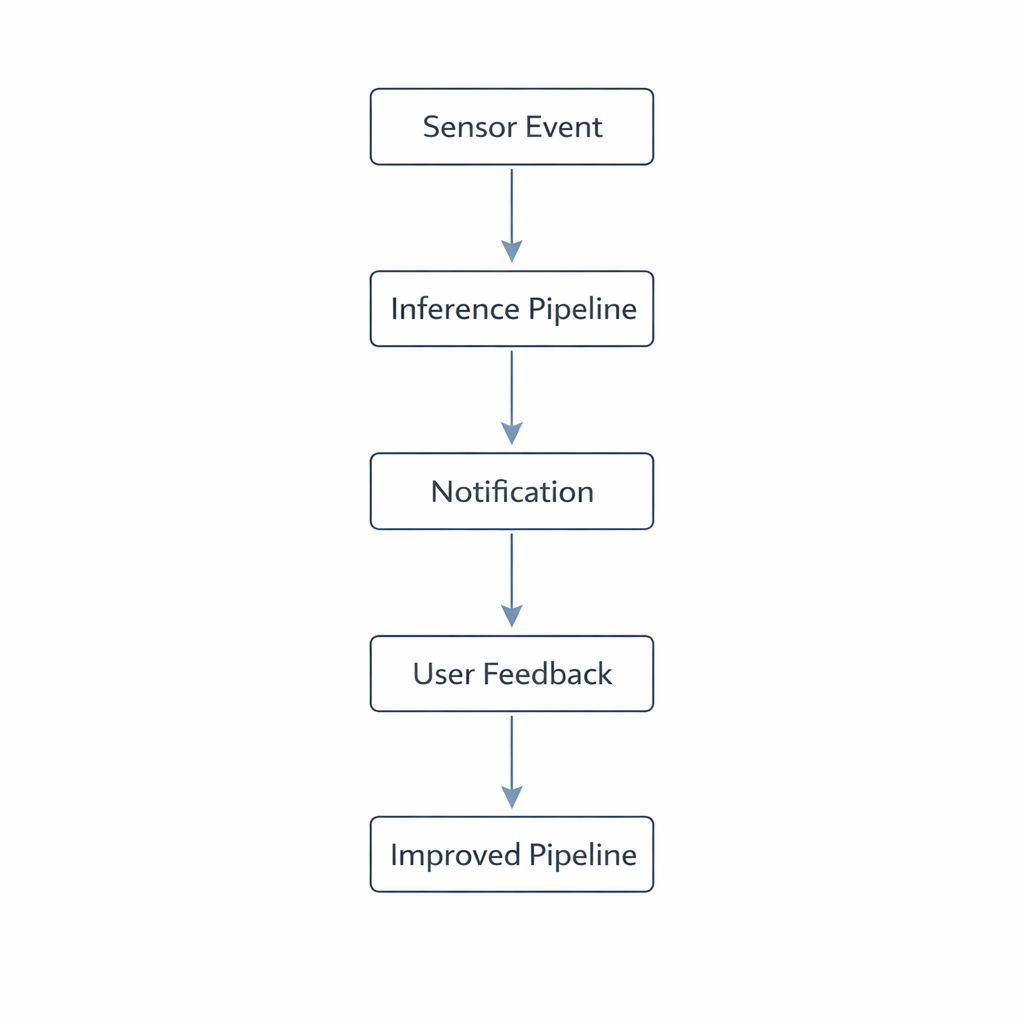

Instead of trying to predict everything perfectly, we designed a feedback loop that leverages the one resource we weren't using: the pet parent's direct observation.

Here's how it works:

Step 1: Initial inference. When a feeding or drinking event completes, our pipeline generates an estimate: "Luna drank approximately 350ml over 2 minutes."

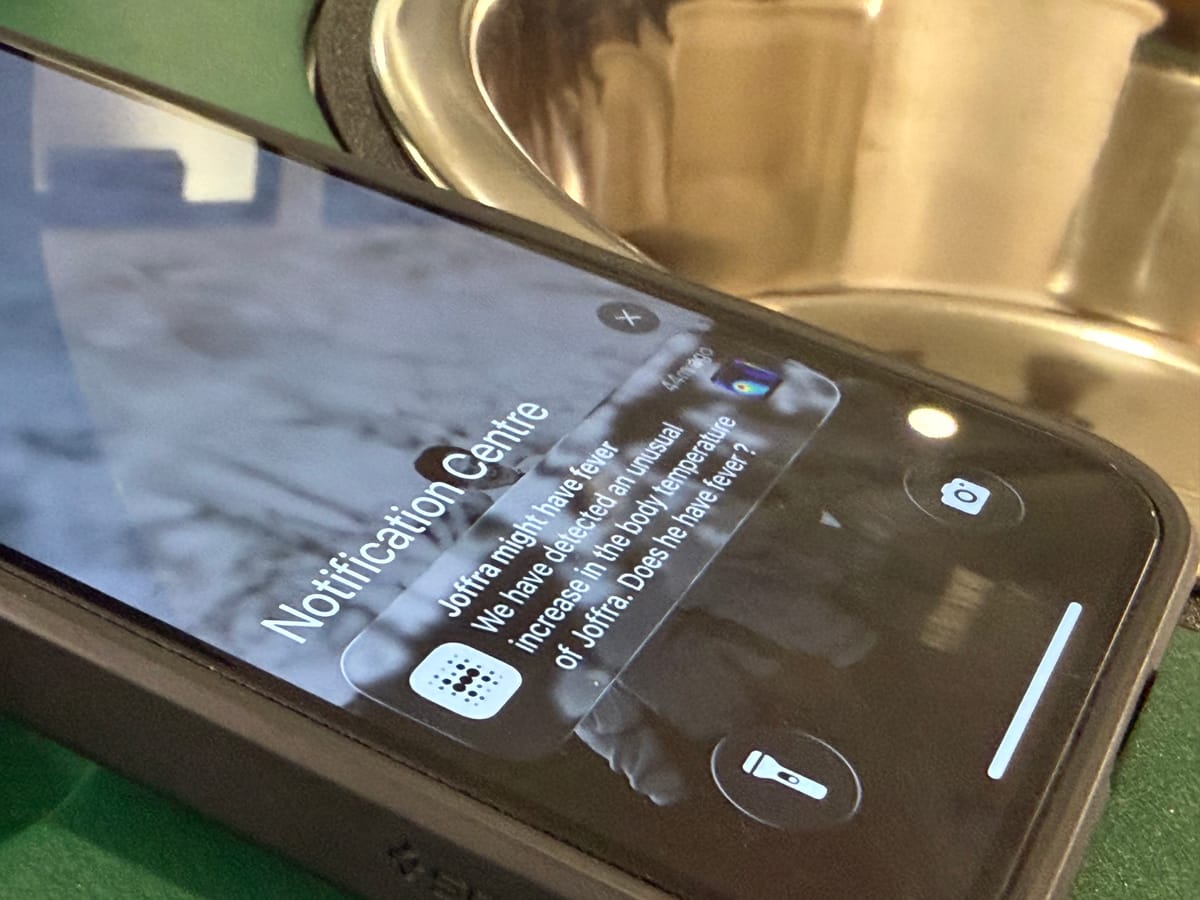

Step 2: Notification with confirmation. We send a push notification to the user showing this inference and asking a simple question: "Does this look right?"

Step 3: User feedback. The user can confirm ("Yes, that's about right") or correct ("No, she actually drank much less—maybe 150ml").

Step 4: Model adaptation. The feedback is logged and used to adjust the inference parameters for that specific dog and environment.

Over time, the system learns the quirks of each household. The dog that always spills 10% of her water? Accounted for. The bowl placed on a slightly uneven floor? Compensated. The thermal sensor angle that consistently underestimates? Adjusted.

Designing for Minimal Friction

The biggest risk with human-in-the-loop systems is feedback fatigue. If you ask users too often, or make the interaction too complex, they stop responding. And a feedback loop without feedback is just a broken loop.

We optimised for three things:

1. Low-frequency prompts. We don't ask for confirmation on every event. The system requests feedback strategically—when confidence is low, when it detects an anomaly, or periodically to validate that calibration hasn't drifted.

2. One-tap responses. The notification includes a "Looks right" button that requires zero typing. Corrections are optional and only requested when the user indicates something is off.

3. Implicit feedback. Not all feedback is explicit. If a user manually logs a meal in the app that contradicts our inference, that's feedback too. We capture these signals passively.

The goal is to extract maximum calibration value with minimum user effort.

What the Feedback Actually Calibrates

Under the hood, user feedback adjusts several significant parameters.

These aren't global model changes—they're per-dog, per-environment adjustments stored as user-specific configuration. The core inference model remains the same; the calibration layer personalises its output.

This architecture has a nice property: new users get reasonable defaults from our aggregate training data, while engaged users get precision that improves over time.

The Broader Lesson

There's a tendency in ML engineering to treat the model as the solution and the user as a passive consumer of predictions. But in applied systems—especially those involving physical sensors and real-world variance—the user is an irreplaceable source of ground truth.

Human-in-the-loop isn't an admission that your model is incomplete. It's a recognition that personalisation at scale requires collaboration between algorithms and the people who live with the results.

Key Takeaways

- Generic models hit a ceiling. Real-world variance in hardware deployments requires per-user calibration.

- Users know ground truth. A well-designed feedback prompt extracts valuable calibration data with minimal friction.

- Personalisation compounds. Each feedback event makes subsequent inferences more accurate, building user trust over time.

- Design for low friction. One-tap confirmations and strategic prompting prevent feedback fatigue.