Designing a Power Button That Works Before Software Exists

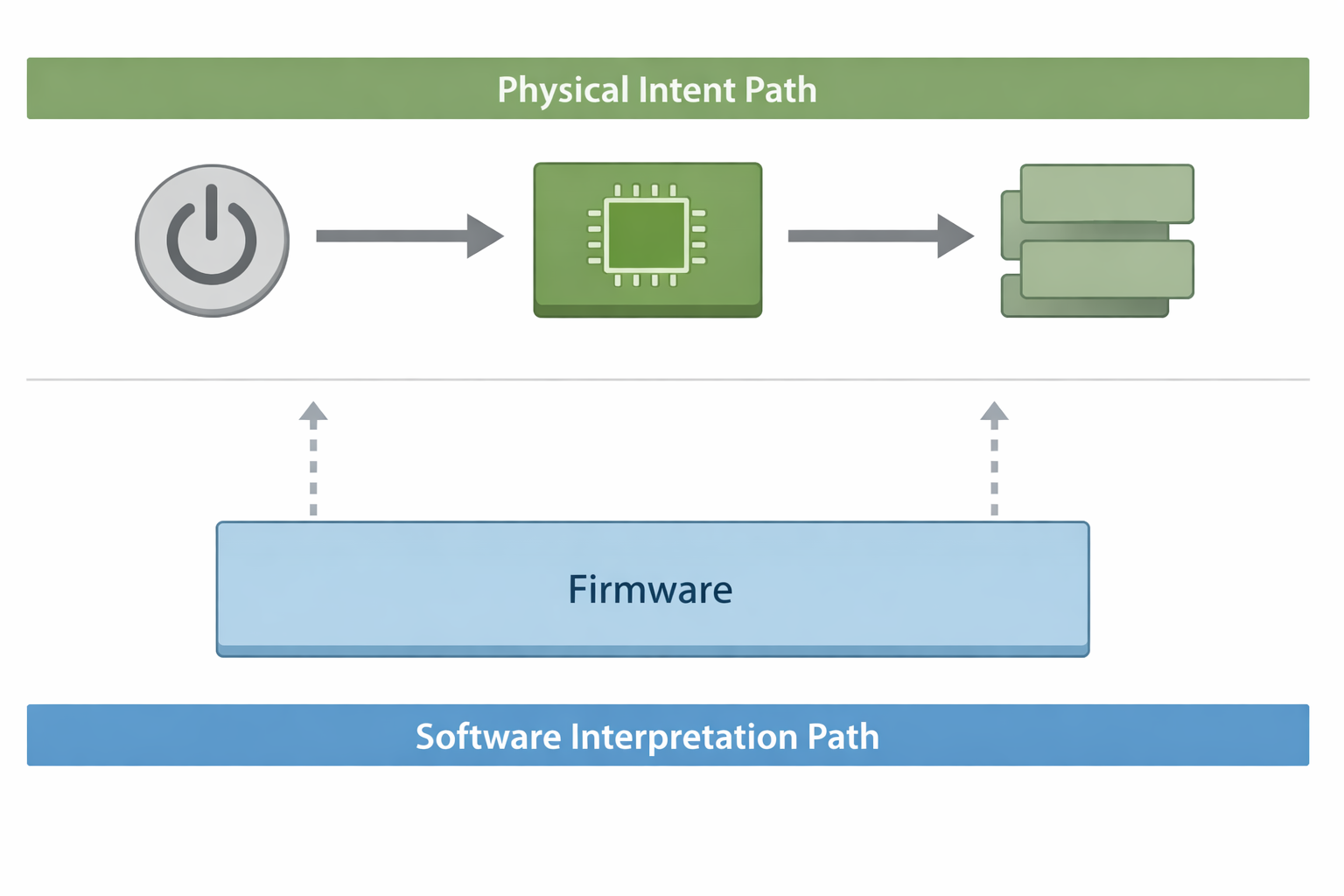

In many products, the power button is treated as a UI element—a cosmetic input whose real meaning only emerges once software is running. Press the button, wait for the logo, let firmware take over. From that point on, everything interesting is assumed to be a software problem.

That assumption breaks down in real devices.

In the physical world, the power button is often the first and last interface a user has with a product. It is pressed when the system is uninitialized, misconfigured, partially assembled, or already malfunctioning. It is pressed when batteries are marginal, rails are collapsing, or firmware is corrupted. It is pressed by users who don’t care about boot stages or reset domains—they care whether the device feels alive.

At Hoomanely, we treat the power button as a hardware-level system feature, not a software shortcut. Its behaviour must be meaningful even when software does not yet exist—or cannot be trusted. Designing that behaviour requires thinking beyond debounce circuits and GPIO interrupts. It requires defining what “power intent” means in the absence of firmware.

This article explores how we approach that problem, and why a power button that works before software exists fundamentally improves reliability, debuggability, and user trust.

Power Intent Exists Before State

The first design question is deceptively simple: what does pressing the button actually mean?

In many designs, a button press is mapped directly to a microcontroller pin. Firmware decides whether that press means “turn on,” “go to sleep,” or “ignore.” This approach assumes three things:

- The MCU is powered

- The MCU is executing valid code

- The system state is well understood

None of these assumptions holds during early bring-up, brownout recovery, field faults, or partially failed units.

A hardware-first power button design starts from a different premise: power intent must be legible before system state is known. A button press should unambiguously request one of a small number of hardware actions, independent of firmware readiness.

Typical intents might include:

- Request system power

- Request system shutdown

- Force a power cycle

- Enter a recovery-safe power state

The key is that these intents are enforced electrically, not interpreted conditionally by software.

Latching Power Without Trusting Firmware

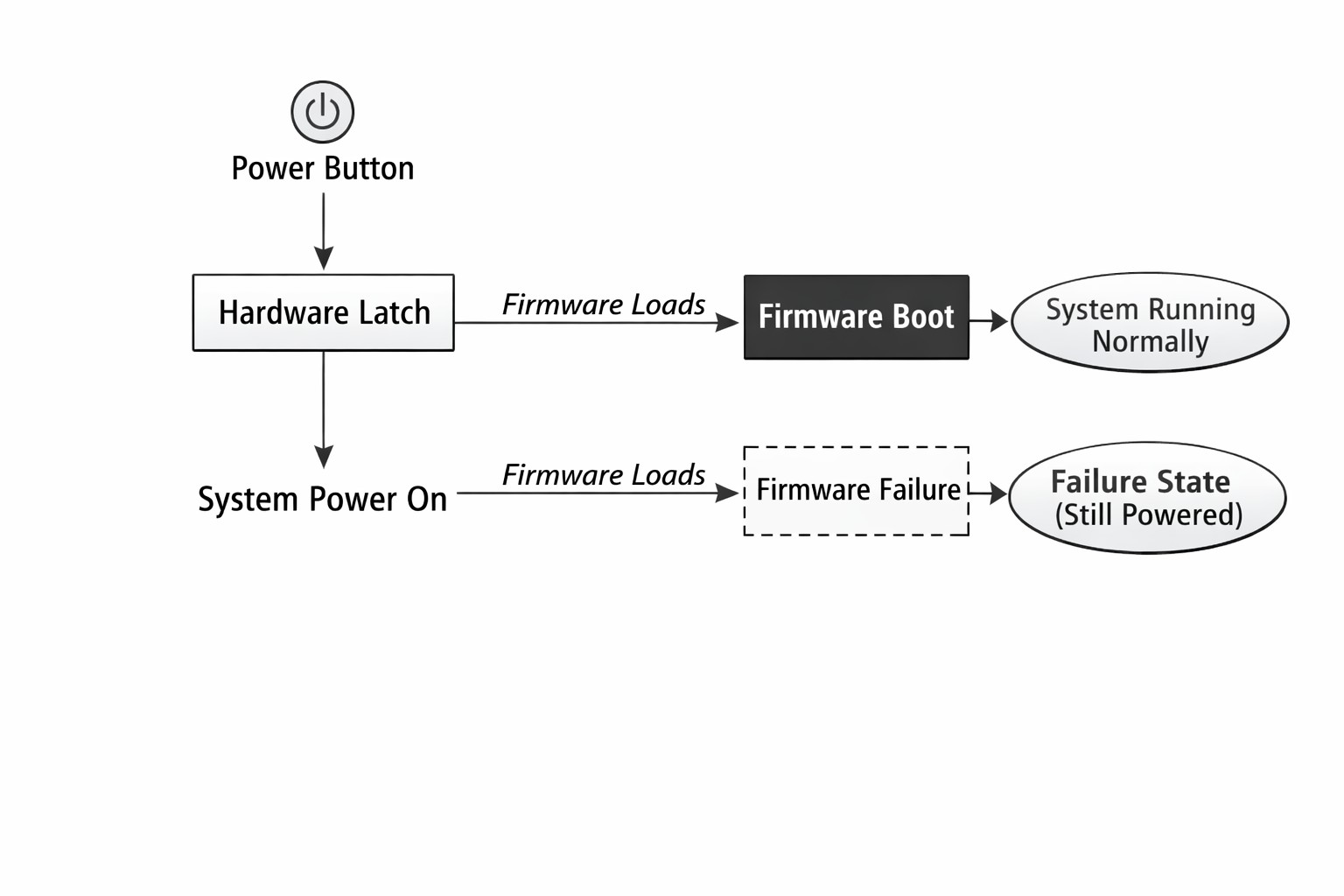

One of the most important shifts is separating power latching from software execution.

If the system requires firmware to keep itself powered, then firmware failure equals device death. From a user’s perspective, the product is bricked—even if the hardware is perfectly functional.

Instead, the act of pressing the power button should:

- Physically latch system power

- Hold that state deterministically

- Allow software to join the system later, not define it

This means the system can:

- Stay powered even if firmware crashes immediately after boot

- Remain on long enough for diagnostics, recovery, or reflashing

- Communicate “I am alive” through hardware indicators alone

From a product standpoint, this single decision dramatically reduces “dead device” reports. From an engineering standpoint, it decouples hardware survivability from software correctness.

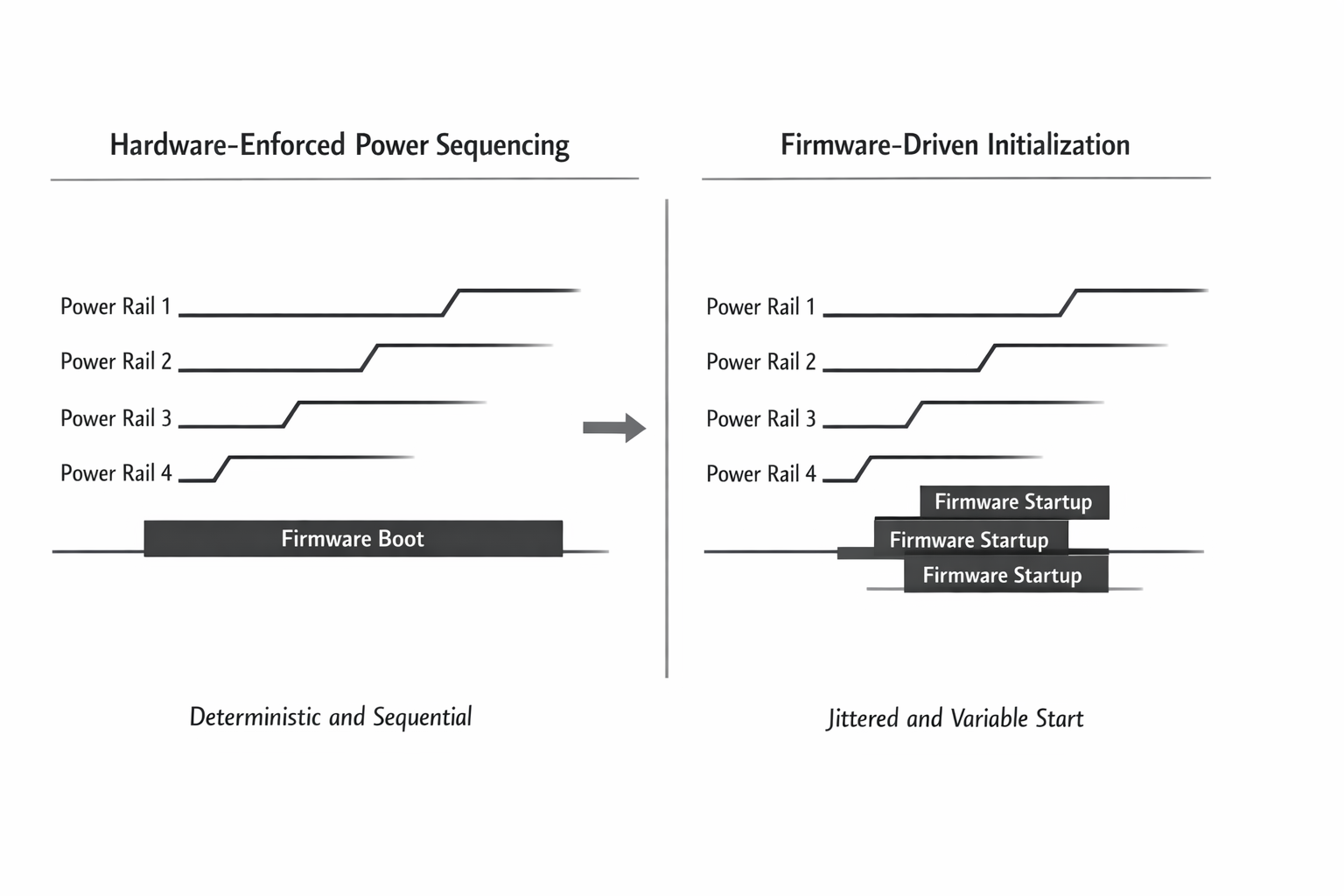

Sequencing Is Part of the Interface

A power button that merely connects power is not enough. The sequence in which rails rise, domains stabilise, and peripherals become active defines whether the system starts cleanly or enters undefined states.

Crucially, this sequence must be:

- Enforced in hardware

- Independent of boot firmware timing

- Predictable under slow or collapsing supplies

This is especially important in systems with:

- Multiple voltage domains

- Mixed-signal components

- High inrush or dynamic loads

By encoding sequencing rules electrically—using enables, dependencies, and gating—the system ensures that pressing the power button always results in the same electrical narrative, regardless of how fast or slow the firmware reacts.

This predictability matters not just for reliability, but for human understanding. Engineers debugging a system need to trust that power behavior is not changing silently based on code paths they can’t yet observe.

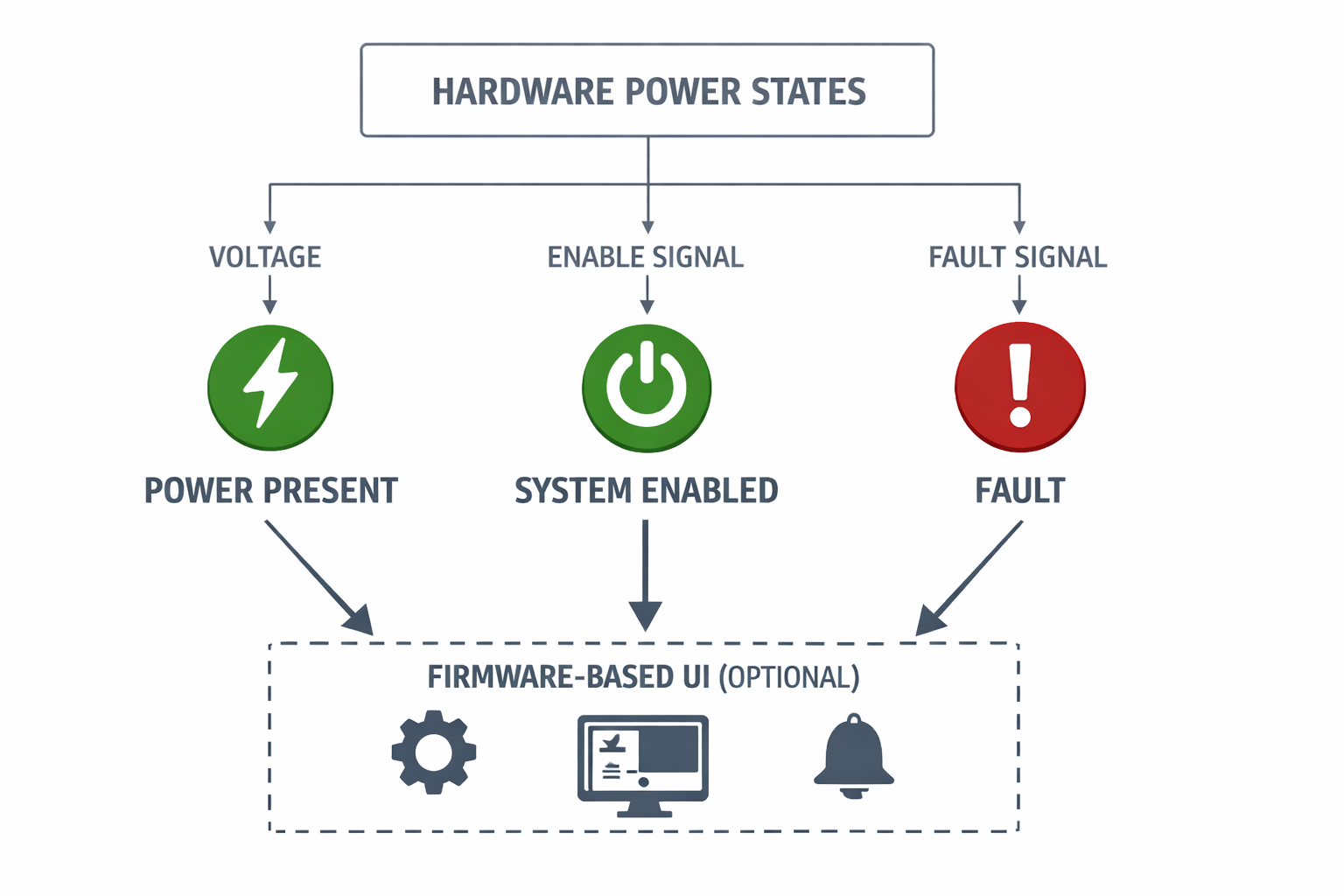

Communicating State Before the Screen Turns On

Users don’t experience schematics or logs—they experience feedback.

A power button that works before software exists must also communicate its state before software exists. That means providing hardware-level signals that indicate:

- Power is present

- The system is intentionally on

- A fault has occurred

- A recovery path is active

This communication is intentionally simple. It does not attempt to encode complex diagnostics. Instead, it answers the user’s first question: Did my action do anything?

When this feedback is absent, users press the button repeatedly. They long-press unpredictably. They attempt resets that were never designed. Many downstream “mystery failures” originate from this moment of uncertainty.

By contrast, when the system responds immediately—through a light, a latch, or a controlled delay—the user learns how the product behaves. That learning compounds into trust.

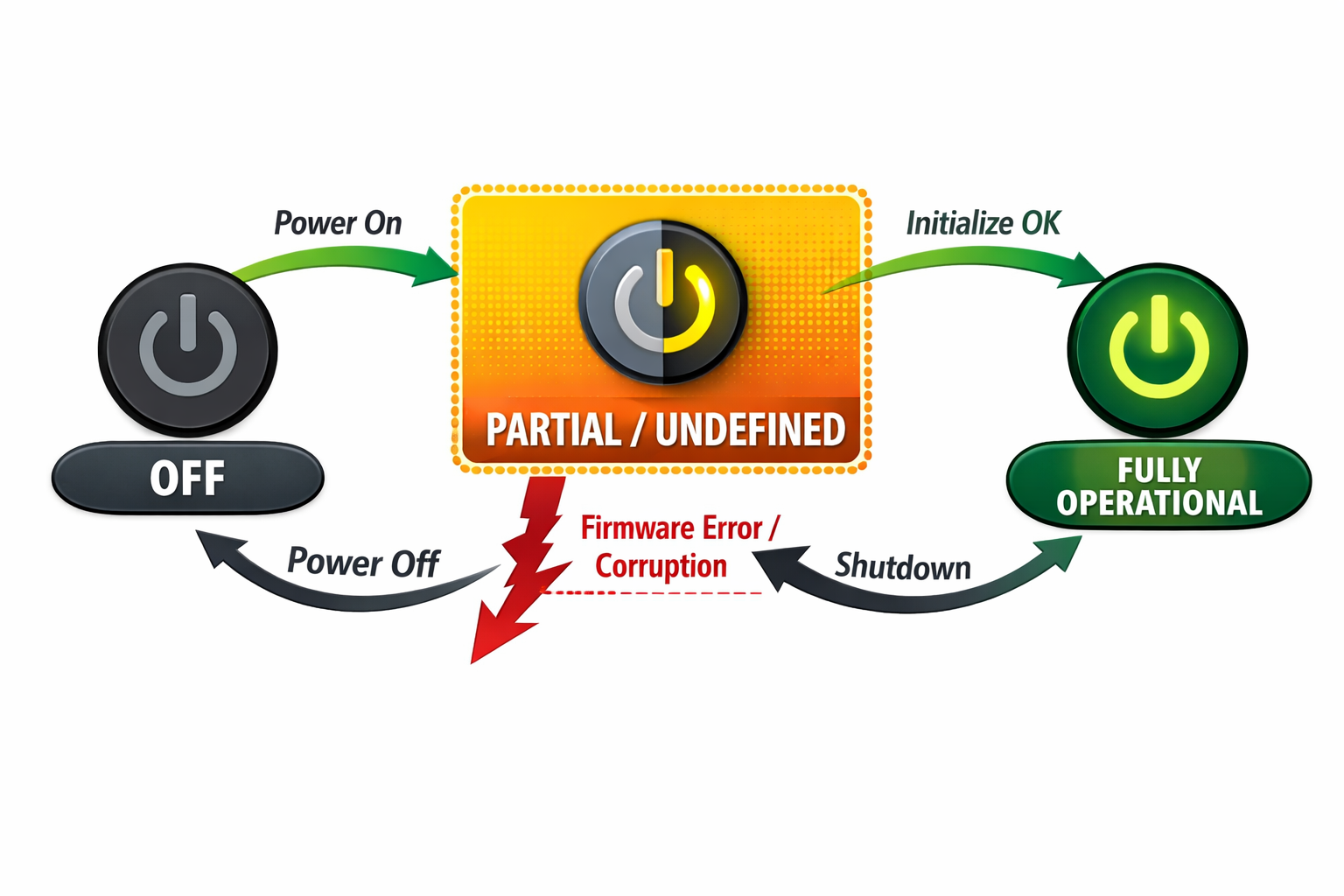

Designing for the Broken Middle

Most designs focus on two states: fully off and fully operational. Real devices spend surprising amounts of time in the middle.

Examples include:

- Firmware that crashes early in boot

- Storage corruption that prevents a full startup

- Peripheral faults that stall initialisation

- Power sources that sag under load

A power button that depends on software logic behaves unpredictably in these states. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it makes things worse.

A hardware-centric design assumes the middle exists—and designs for it explicitly.

In these cases, the power button must:

- Still responds deterministically

- Allow safe power cycling

- Enable entry into known recovery conditions

This is not about adding complexity. It’s about limiting ambiguity. When the system is broken, the button should still mean something simple and reliable.

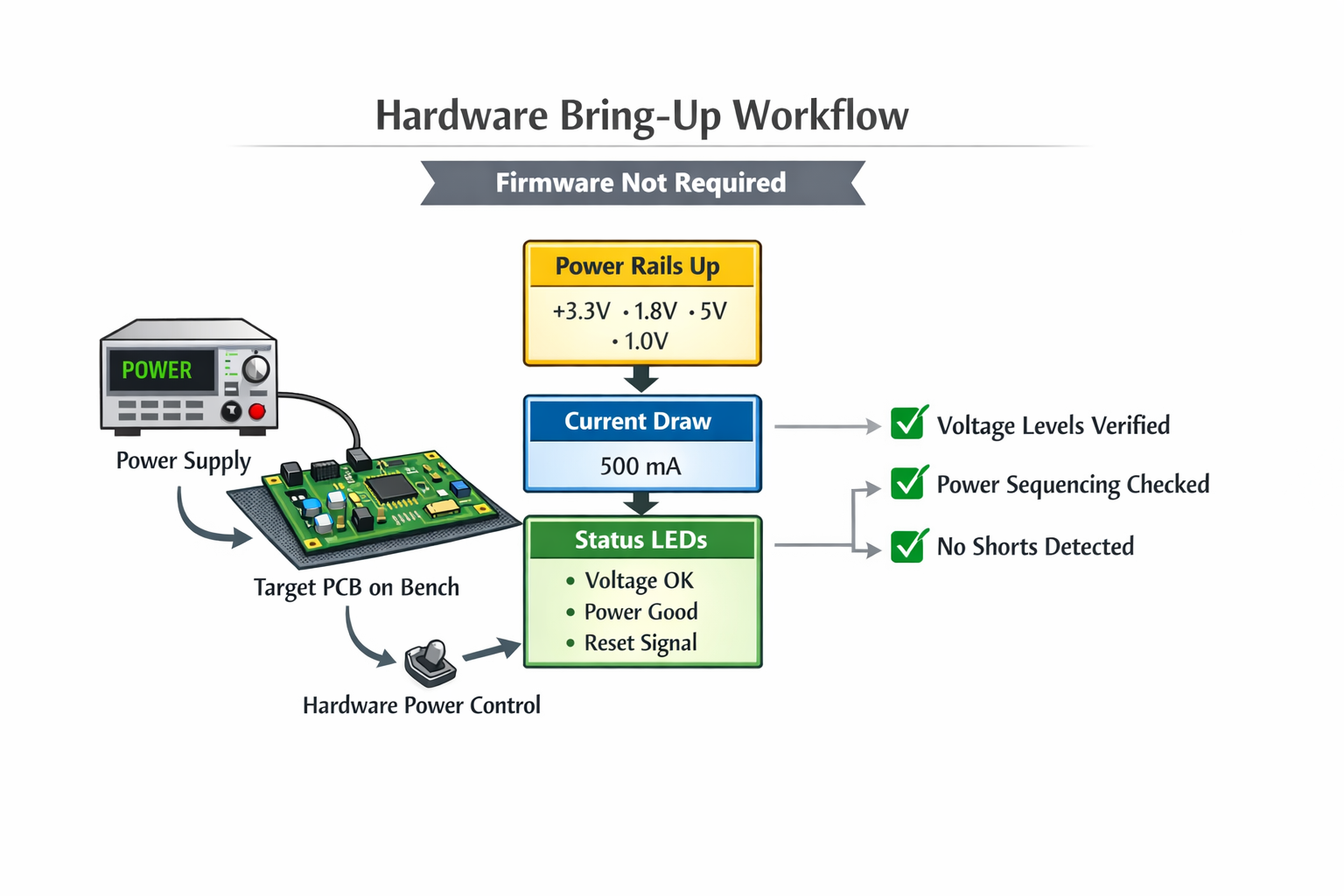

Manufacturing and Bring-Up Benefits

The benefits of this approach appear long before the product reaches users.

During manufacturing and bring-up:

- Boards can be powered and evaluated without firmware

- Power behaviour can be validated independently

- Assembly issues can be detected through power-only tests

Engineers can answer basic questions immediately:

- Does the board turn on?

- Do rails sequence correctly?

- Is current consumption sane?

This reduces the dependency on early firmware, which is often incomplete, unstable, or evolving rapidly. It also shortens the feedback loop between hardware issues and their root causes.

In practice, this approach consistently reduces bring-up time and increases early confidence in the physical system.

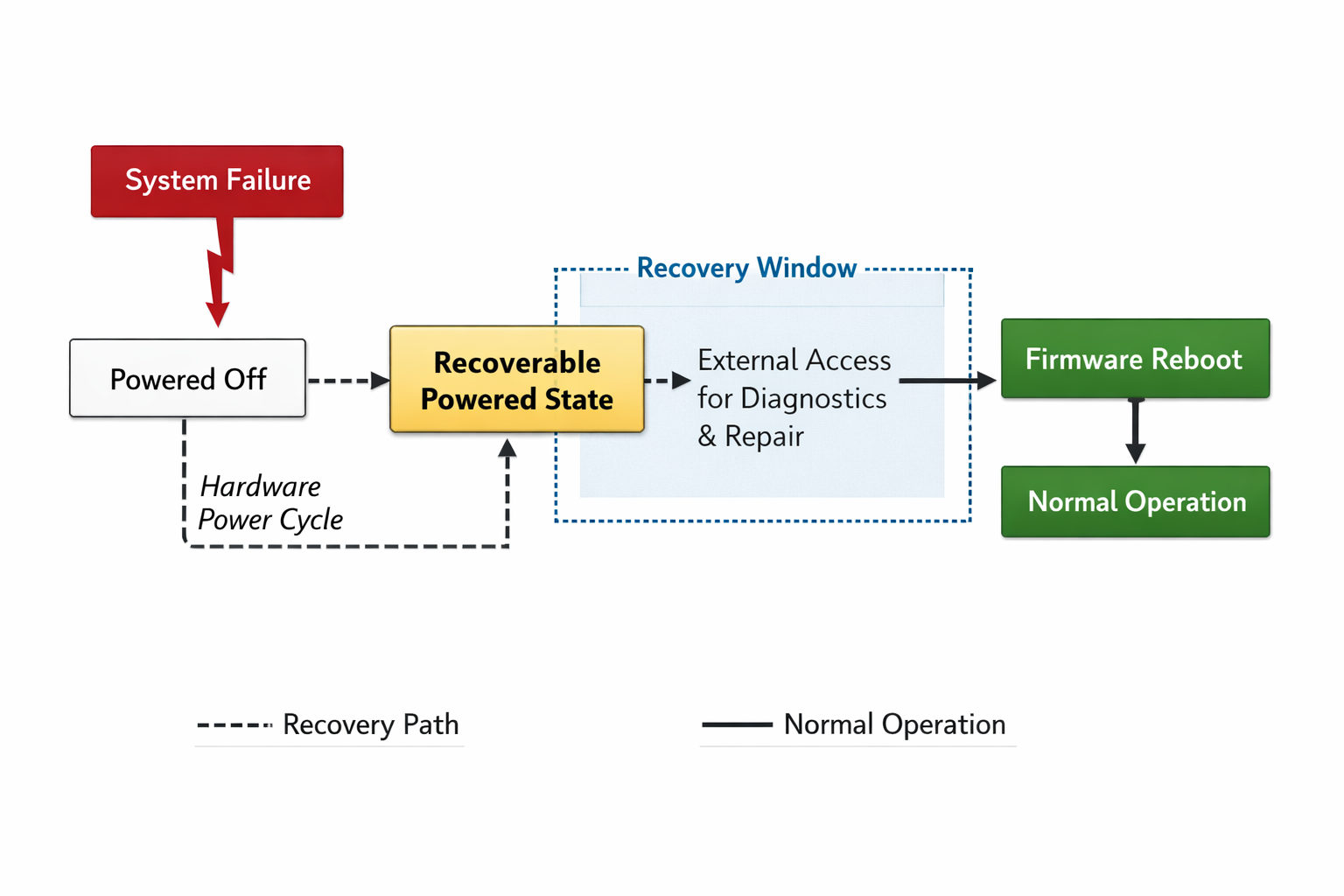

Recovery Is a First-Class Use Case

Eventually, every complex product encounters a unit that doesn’t boot. The difference between a resilient system and a fragile one is whether recovery is possible without disassembly or specialised tools.

A power button designed at the hardware level enables recovery by:

- Guaranteeing access to a powered state

- Providing time windows where recovery interfaces are active

- Allowing forced resets that do not depend on firmware cooperation

Importantly, this does not require exposing dangerous interfaces or weakening security. It simply ensures that power control itself is not held hostage by corrupted code.

From a fleet perspective, this dramatically improves recoverability. From a user perspective, it turns a potentially fatal failure into a temporary inconvenience.

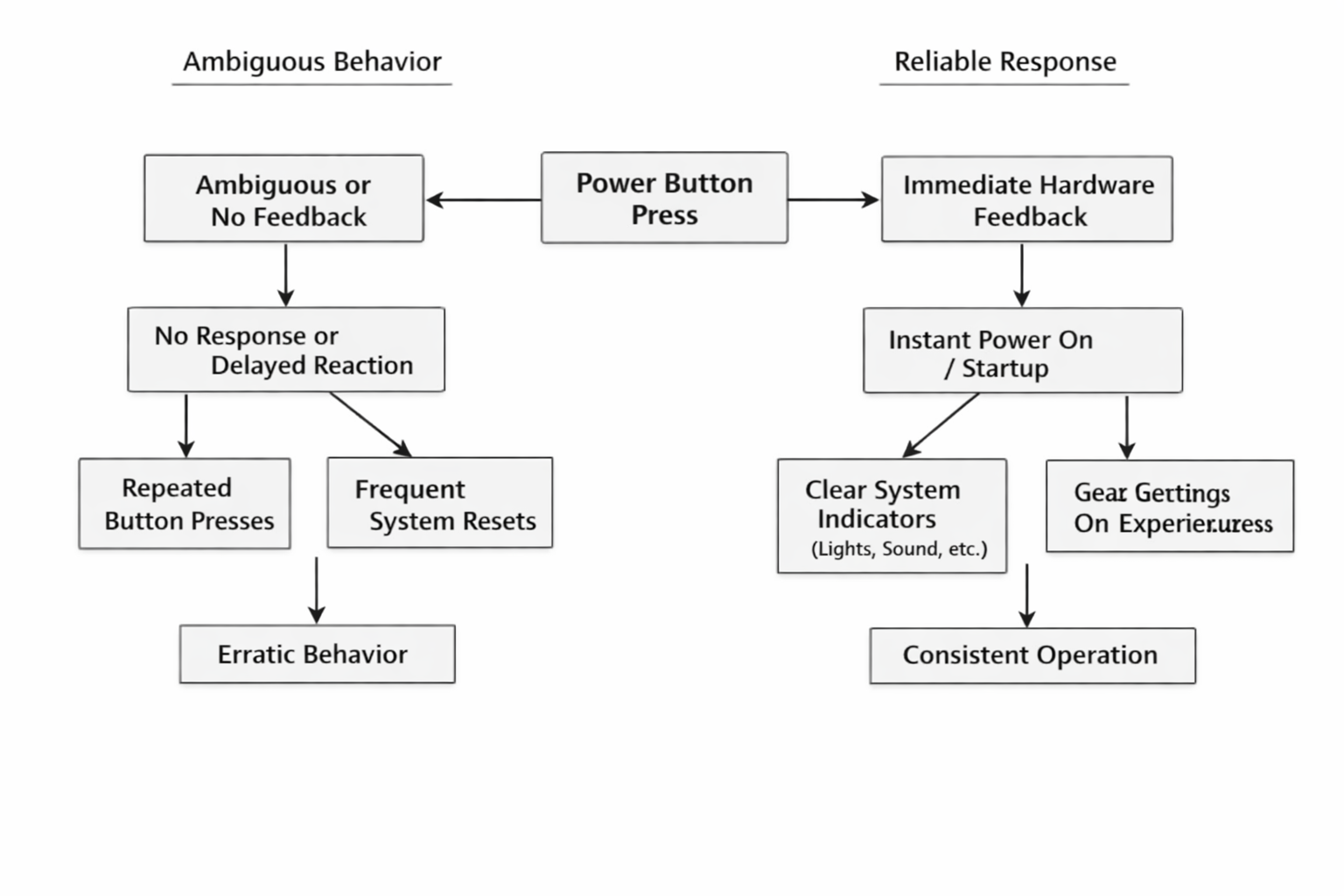

Power Buttons Shape User Trust

Most users never think about the power button—until it fails them.

When a device does not respond immediately, users assume the worst. They lose confidence not just in the button, but in the product as a whole. No amount of later reliability compensates for that first impression.

By contrast, a power button that:

- Responds instantly

- Behaves consistently

- Communicates clearly

sets the tone for the entire product experience.

This is not a cosmetic win. It directly correlates with fewer returns, fewer support tickets, and fewer “it just stopped working” reports that have no clear technical cause.

Designing the First Interface Last

Ironically, the power button is often designed last. It’s wired once the rest of the system is “done,” squeezed into available space, and delegated to firmware behaviour.

At Hoomanely, we invert that order.

We treat the power button as the first interface the system must honor, because it defines how everything else can fail safely. Once power intent is clear, enforced, and observable, software becomes more robust—not because it’s better written, but because it’s no longer carrying responsibility it cannot reliably fulfil.

A power button that works before software exists is not an edge case solution. It is a statement of design maturity.

It says: this system understands itself, even when it is broken.

And that understanding is what allows complex products to survive the real world.