Designing Deterministic Timelines from Noisy Events and AI Inference

Timelines used to be simple. A user action happened, an event was logged, and the system displayed it in order. Append-only. Mostly synchronous. Easy to reason about. That model no longer holds.

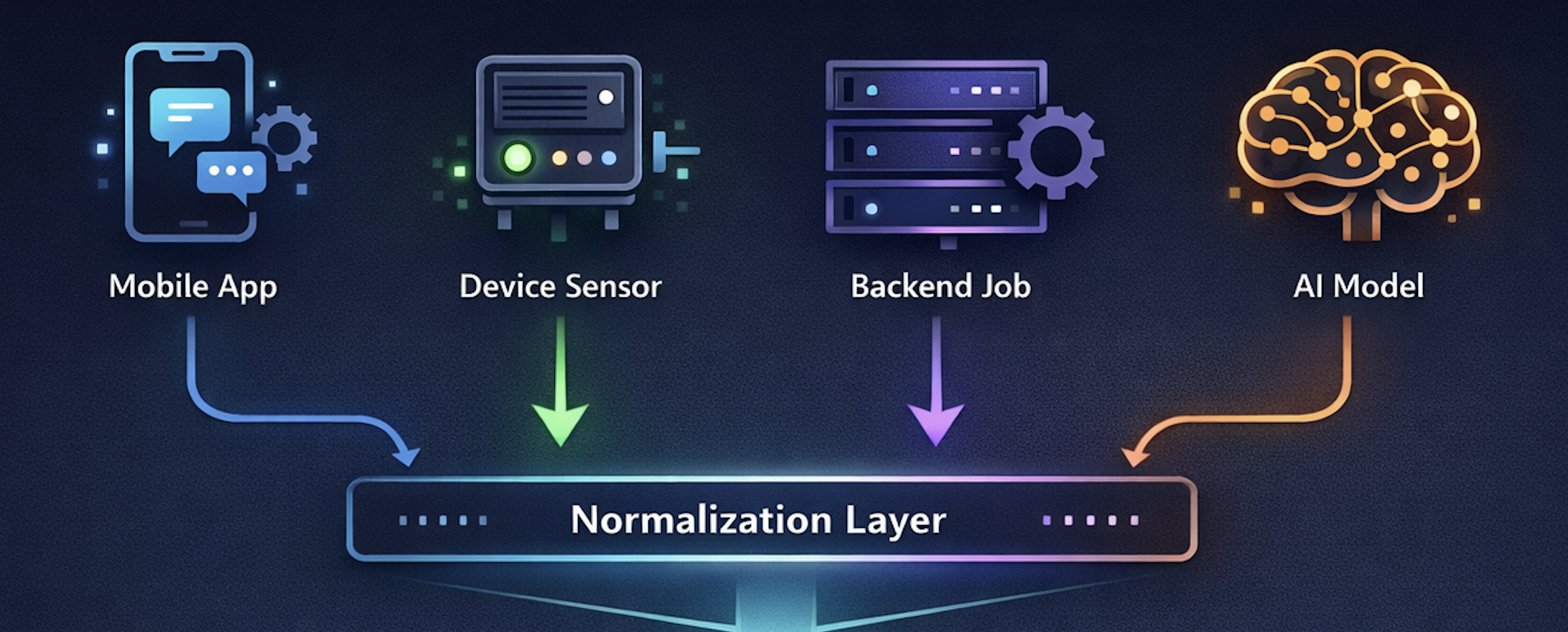

Modern product timelines are assembled from distributed, asynchronous, and probabilistic inputs: user actions from mobile devices, background jobs, delayed sensor uploads, enrichment pipelines, retries, deduplications, and increasingly, AI-generated inferences that may arrive minutes or hours later—and may even change over time.

Despite this chaos, users expect timelines to feel stable, ordered, and trustworthy. Once something appears in a timeline, it should not jump around, disappear mysteriously, or contradict itself without explanation. The timeline becomes a narrative, not just a log.

This post explores how deterministic timelines are engineered, not assumed. We’ll walk through architectural strategies that turn noisy, non-deterministic inputs into a coherent, explainable sequence of events—without pretending the underlying world is clean or perfectly ordered.

The Core Problem: Non-Determinism Everywhere

Before designing solutions, it’s important to name the sources of non-determinism explicitly. Most real-world timelines combine signals with very different behaviors:

- Human-generated events

Button taps, app opens, device interactions. Usually immediate, but not guaranteed to arrive once or in order. - System-generated events

Background syncs, retries, batch processors, delayed jobs. Often duplicated or reordered. - Device or sensor events

Buffered locally, uploaded later, sometimes backfilled after connectivity returns. - AI-generated insights

Derived events based on probabilistic models, evolving confidence, and reprocessing.

Each of these sources violates at least one comforting assumption:

- Events arrive late

- Events arrive twice

- Events arrive out of order

- Events are corrected later

- Events are inferred, not observed

Determinism as a Product Requirement

A deterministic timeline is not one where data is perfect. It is one where given the same inputs and rules, the output timeline is always the same.

From a user’s perspective, this translates into:

- Items don’t reshuffle unexpectedly

- Corrections feel intentional, not buggy

- AI insights don’t contradict earlier entries without context

- The story remains understandable even as data evolves

From a system perspective, determinism means:

- Clear ordering rules

- Explicit reconciliation logic

- Versioned interpretation, not silent mutation

Normalize Before You Order

One of the most important—and most overlooked—steps is event normalization. Before events ever touch a timeline, they should be transformed into a canonical internal shape.

- Event identity

- A stable event ID

- An idempotency or deduplication key

- Event type

- Observation, action, system update, inference

- Time dimensions

observed_at(when it happened)received_at(when the system saw it)effective_at(when it should appear in the narrative)

- Confidence or reliability

- Explicit or implicit

- Mutability class

- Immutable fact vs revisable inference

Normalization is not about cleaning data—it’s about making uncertainty explicit. Once every event carries the same conceptual fields, the system can reason about them consistently.

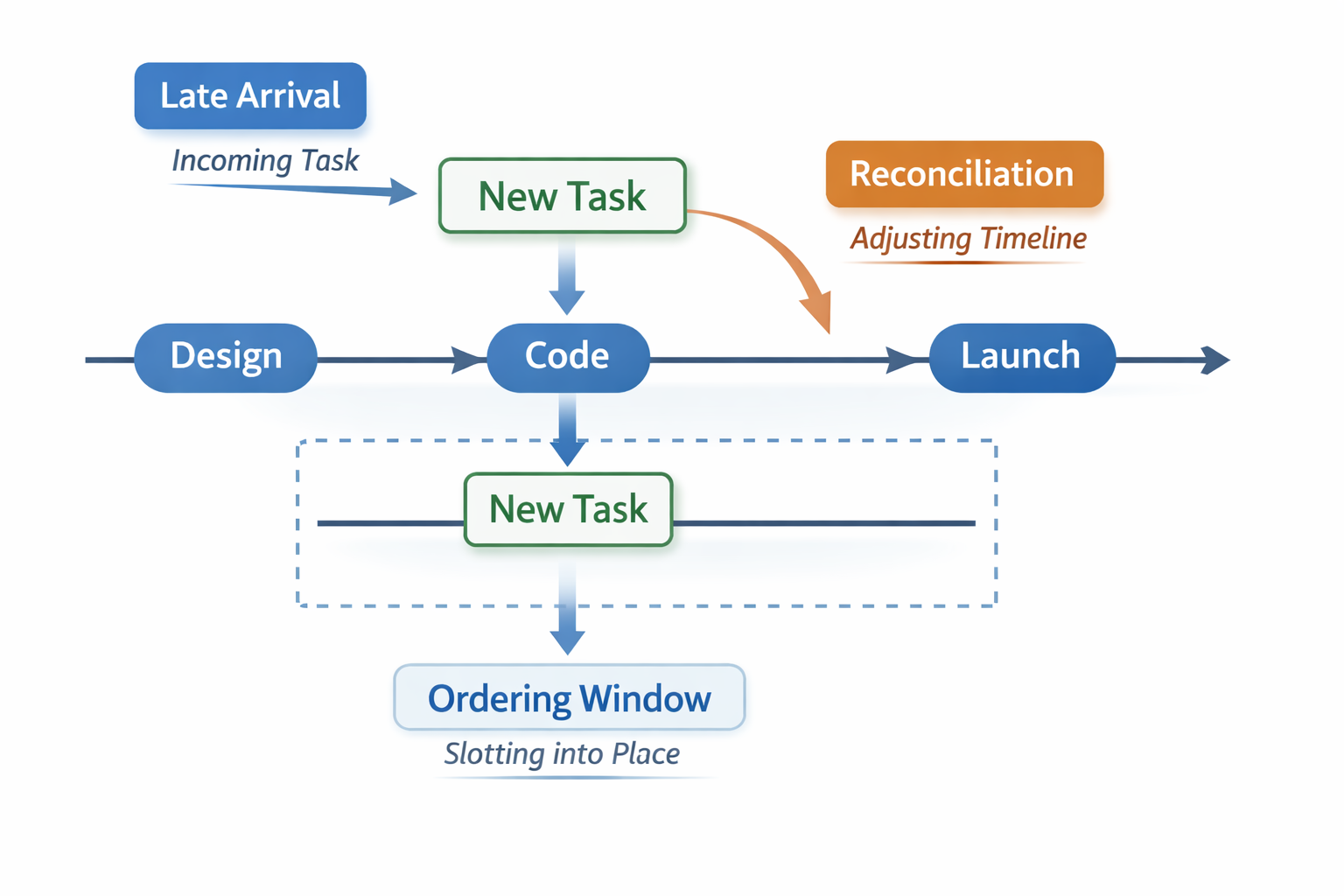

Separate Ordering From Arrival

A deterministic timeline never orders events by arrival time. Instead, it defines explicit ordering semantics, often using multiple layers:

- Primary ordering key

Usuallyeffective_atorobserved_at - Secondary tie-breakers

- Event class priority (e.g., user actions before system enrichments)

- Source precedence

- Stable hashes or IDs

- Insertion rules for late arrivals

- Allowed window for backfill

- Rules for when an event is attached vs inserted

A key insight: ordering rules must be static and documented.

If ordering logic changes dynamically, determinism is lost. Many mature systems treat ordering logic as part of the schema contract, not application code that can drift silently.

Design for Late and Out-of-Order Events

Late data is inevitable. The question is not if it happens, but how the timeline reacts. There are three common strategies:

1. Hard Cutoff

After a certain time window, late events are ignored or summarized elsewhere.

- Simple

- Highly deterministic

- Risk of missing meaningful context

2. Soft Backfill

Late events are inserted but visually marked or grouped.

- Preserves accuracy

- Requires careful UI treatment

3. Reconciliation Without Reordering

Late events update metadata or annotations but do not move existing items.

- Strong narrative stability

- Slightly less precise ordering

Deterministic timelines usually favor predictability over perfect chronology. Users tolerate slight imprecision far more than sudden reshuffling.

Reconciling Without Rewriting History

One of the most dangerous anti-patterns in timeline systems is rewriting past events silently. When conflicting or corrected data arrives, deterministic systems prefer:

- Supersession, not mutation

- Versioning, not overwrites

- Explicit correction events

For example:

- Instead of changing an earlier entry, emit a new event: “Previous observation corrected”

- Instead of deleting, mark as superseded

This preserves auditability and user trust. The timeline becomes a record of understanding over time, not a constantly edited fiction. This approach becomes especially important once AI enters the picture.

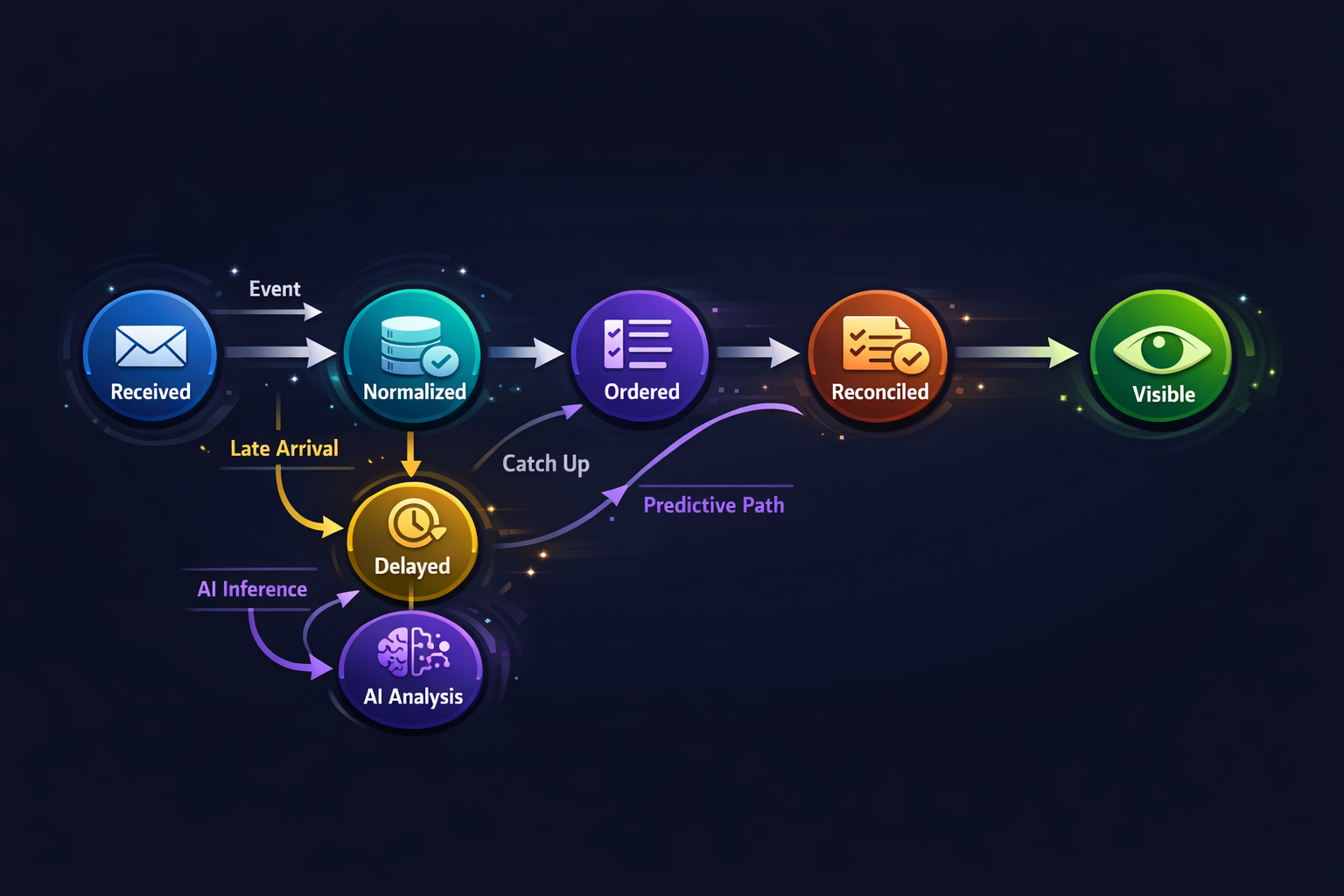

Treat AI Inference as a First-Class

AI-derived timeline entries are fundamentally different from observed facts.

- Probabilistic

- Model-dependent

- Subject to reprocessing

- Often confidence-weighted

Deterministic timelines make this difference visible in the data model:

- AI events carry:

- Model version

- Confidence score

- Inference time

- AI events are usually:

- Append-only

- Revisable via follow-up inference events

- Linked to the source evidence they depend on

Critically, AI events should not retroactively change observed events. They interpret them. This distinction keeps timelines explainable even as models improve.

In systems built at Hoomanely, timelines often combine direct interactions with derived insights generated later. For example, device-generated signals may arrive first, while higher-level interpretations appear only after aggregation and inference.

The architectural choice has consistently been to:

- Preserve raw observations as immutable anchors

- Layer interpretations on top

- Avoid retroactive reordering once users have seen an entry

This approach has proven especially important for maintaining trust in pet-related narratives, where users expect consistency and clarity, even as understanding deepens over time.

Narrative Stability as a Design Constraint

A deterministic timeline is as much a product design problem as an engineering one. Some guiding principles that help:

- What the user has seen should not move

- Corrections should be visible, not silent

- Uncertainty should be labeled, not hidden

- AI confidence should be implicit or explicit, never implied as fact

Engineering teams often encode these as invariants:

- “Once rendered, ordering is frozen”

- “Inference never mutates observation”

- “All corrections emit events”

These constraints simplify reasoning across the entire stack.

Observability for Timelines

You cannot trust what you cannot observe. Deterministic timeline systems benefit from:

- Metrics on late-arrival frequency

- Counts of reconciliation events

- Drift between observed_at and effective_at

- AI revision rates

These signals help teams detect when timelines are becoming unstable long before users complain.

Takeaways

- Deterministic timelines are engineered, not emergent

- Normalization is the foundation of consistency

- Ordering rules must be explicit and stable

- Late data is handled, not feared

- AI inference should interpret history, not rewrite it

- Narrative stability matters as much as correctness

When done right, timelines become something users trust instinctively—even when they don’t know why.