Designing Hardware to a Bus Spec: From Complexity to Clarity

Introduction: The Challenge That Wasn't

There's a moment in every ambitious engineering project where you step back and think, "What have we gotten ourselves into?" For me, that moment came when we committed to designing all Hoomanely products around the vBus architecture. Not just one product. Not just one product line. Everything.

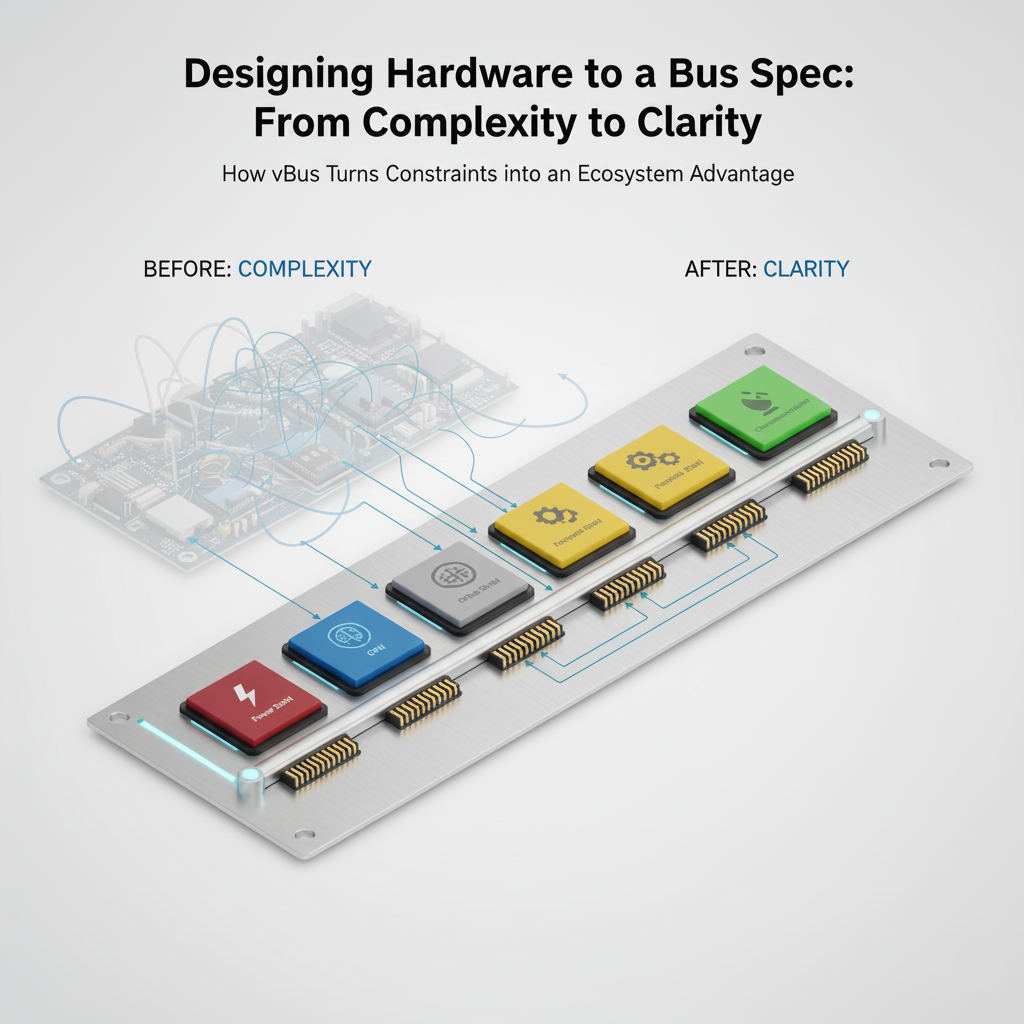

The challenge seemed daunting: how do you design diverse hardware—from industrial gateways to battery-powered sensors to robotic controllers—all conforming to the same rigid connector and communication standard? Wouldn't that limit creativity? Wouldn't we be forcing square pegs into round holes?

Here's the surprising truth I discovered: designing to a specification is actually liberating, not limiting. What initially felt like handcuffs turned out to be guardrails that guided us toward better, faster, more coherent designs. The complexity I feared transformed into elegant simplicity once the architecture clicked into place.

Today, I want to share that journey—how we approach hardware design at Hoomanely when every product must comply with vBus, and why the constraint-based methodology has become our secret weapon for rapid development.

The Fundamental Shift: Products to Ecosystems

Traditional hardware development follows a familiar pattern: identify a market need, design a complete product around that need, optimize for cost and performance, ship it. Each product is a self-contained unit. If you need something different, you design a completely new product.

We've flipped that paradigm entirely. At Hoomanely, we don't design products—we design ecosystem participants.

Every piece of hardware we create is conceived from day one as a module that will live within the vBus ecosystem. This means asking different questions during the design process:

- Instead of "What does this product need to do?" we ask "What role does this module play in the system?"

- Instead of "How do we connect these components?" we ask "Which vBus connector blocks does this module require?"

- Instead of "Can we add this feature?" we ask "Does this feature fit within our pin budget and power envelope?"

This shift in thinking might seem subtle, but it fundamentally changes how hardware gets designed.

The Building Blocks: A Modular Formula

Through iteration and experimentation, we've converged on a standard product architecture that serves as the template for virtually everything we build:

Core Components:

- Peripheral SoM(s) - The functional modules that do the actual work (sensing, actuation, processing)

- Power SoM - The energy source and distribution hub

- Carrier PCB - The motherboard that physically and electrically connects everything

- Communication SoM - The gateway to external networks and devices

Think of it as a hardware grammar—subjects, verbs, and objects that can be arranged into infinite sentences while following consistent rules.

Why This Structure Works

Separation of Concerns: Each module type has a clear, focused purpose. Power modules worry about voltage regulation and current delivery. Peripheral modules focus on their specific sensors or actuators. The CPU module handles computation and orchestration. This separation makes each module simpler to design and test.

Parallel Development: Different teams can work on different modules simultaneously without stepping on each other's toes. The power team optimizes charging circuits while the sensor team perfects their IMU fusion algorithm—both confident their modules will work together because vBus defines the interface.

Risk Reduction: When modules have defined interfaces, you can breadboard and test them independently before system integration. A Peripheral SoM can be validated standalone, then dropped into the system with high confidence it will work.

Inventory Optimization: Manufacturing can stock a library of validated modules and quickly assemble them into various product configurations without custom PCB runs for each variant.

The Classification System: Variations on a Theme

Early in our vBus journey, we hit an interesting problem. The Power SoM concept was great—a standardized power delivery module—but a robotics product needing 24V at 10A has vastly different requirements than a wearable device running on 3.7V at 200mA. Do we create two completely different "standards"? That defeats the purpose.

Our solution: classification hierarchies. Each SoM family (Power, Peripheral, Communication, CPU) has multiple classes with different capabilities but identical connector pinouts and communication protocols.

Power SoM Classification: An Example

Let's dive into Power SoMs as a concrete example:

Power SoM Class 1 - High Power/High Voltage:

- Input: 5-24V DC or USB-C PD

- Output: 5V @ 5A, 3.3V @ 3A, 1.8V @ 1A

- Connector: 30-pin high-current rated

- Use case: Industrial equipment, robotics, motor controllers

- Features: Overcurrent protection, wide input range, thermal monitoring

Power SoM Class 2 - Medium Power/Standard Voltage:

- Input: 5-24V DC or USB-C PD

- Output: 5V @ 2A, 3.3V @ 2A, 1.8V @ 500mA

- Connector: 30-pin standard

- Use case: General embedded systems, development boards

- Features: USB-C negotiation, battery charging, power path management

Power SoM Class 3 - Low Power/Battery Optimized:

- Input: Single-cell LiPo (3.7V) or dual-cell (7.4V)

- Output: 3.3V @ 1A, 1.8V @ 500mA (no 5V rail)

- Connector: 30-pin standard

- Use case: Wearables, wireless sensors, portable devices

- Features: Ultra-low quiescent current, fuel gauge, solar charging support

Power SoM Class 4 - High Voltage/Low Current:

- Input: 48-110V DC (PoE, telecom, industrial)

- Output: 5V @ 500mA, 3.3V @ 500mA, 1.8V @ 200mA

- Connector: 30-pin with enhanced isolation

- Use case: Network equipment, industrial sensors, PoE devices

- Features: Galvanic isolation, surge protection, wide temperature range

The Brilliance of This Approach

Here's what makes classification powerful: from the Carrier PCB's perspective, all Power SoMs look identical. The pinout is the same. The enable signal works the same way. The I2C communication protocol for status reporting is identical. The Carrier board doesn't need to know which class of Power SoM is installed—it just works.

This means:

- A single Carrier PCB design can support multiple power configurations

- Products can be easily up-specced or down-specced by swapping Power SoM classes

- Field upgrades are possible without redesigning the entire system

- Development teams can prototype with Class 2 (easy to source, USB-powered) and deploy with Class 1 (ruggedized, industrial)

Extending Classification to Other SoM Families

The same classification strategy applies across the ecosystem:

Peripheral SoM Classes:

- Class 1: Basic sensors (temperature, humidity, simple digital/analog I/O)

- Class 2: Motion and inertial sensors (IMU, gyroscopes, accelerometers)

- Class 3: Vision modules (cameras, image processors, AI inference)

- Class 4: Industrial I/O (isolated inputs/outputs, 4-20mA loops, modbus)

- Class 5: Actuator controllers (motor drivers, servo controllers, valve actuators)

Communication SoM Classes:

- Class 1: Short-range wireless (BLE, Zigbee, Thread)

- Class 2: Wi-Fi and local networking (2.4/5GHz, Ethernet backup)

- Class 3: Cellular and wide-area (4G/LTE, 5G, NB-IoT)

- Class 4: Long-range, low-power (LoRa, LoRaWAN, satellite)

- Class 5: Industrial protocols (Profinet, EtherCAT, CAN over distance)

CPU SoM Classes:

- Class 1: Microcontroller-based (Cortex-M4/M7, real-time focus)

- Class 2: Basic application processor (Cortex-A7/A35, Linux-capable, limited I/O)

- Class 3: Performance application processor (Cortex-A53/A55, multi-core, rich peripherals)

- Class 4: High-performance with acceleration (A72/A76, GPU, NPU for AI/ML)

- Class 5: FPGA-integrated (software-defined hardware, custom interfaces)

Each class addresses specific performance points, but maintains interface compatibility within its family.

Design Process: From Concept to vBus Compliance

Let me walk you through how we actually design a new product using this framework. I'll use a real example: an industrial environmental monitoring system we recently developed for our product line.

Step 1: Define Product Requirements

Our product planning identified a market need:

- Temperature, humidity, and air quality monitoring for industrial facilities

- 4-20mA outputs for integration with existing HVAC systems

- Modbus RTU communication with building management systems

- PoE-powered for easy installation

- Wall-mounted enclosure suitable for commercial environments

Traditional approach? Design a custom PCB with all these features integrated. Our approach? Break it into modules.

Step 2: Select SoM Classes

We mapped product requirements to our classification system:

Power SoM: Class 4 (PoE input, isolated, low current sufficient for sensors)

Peripheral SoMs:

- 1× Class 1 (environmental sensors: BME680 for temp/humidity/air quality)

- 1× Class 4 (industrial I/O: isolated 4-20mA DACs)

Communication SoM: Class 5 (Modbus RTU master, RS-485 interface)

CPU SoM: Class 2 (basic Linux system, sufficient for logging and Modbus protocol, extensive I/O not needed)

Carrier PCB: Custom design to fit wall-mount enclosure and provide terminal blocks for external connections

Step 3: Design Within Constraints

Here's where the vBus discipline kicks in. Each module must:

Respect Pin Budget: The environmental sensor Peripheral SoM (Class 1, 40-pin) must:

- Use standard power pins (5V, 3.3V, GND) - 8 pins

- Implement full Communication Block (FDCAN, I2C, INT) - 6 pins

- Include Programming Block (SWD, UART, BOOT) - 8 pins

- Provide Status LED interface - 1 pin

- Accept Enable signal - 1 pin

- That leaves 16 pins for module-specific functions (additional GPIO, analog, custom interfaces)

This pin budget exercise happens before schematic design. It's a forcing function that eliminates scope creep and ensures compatibility.

Honor Communication Protocols: Sensor data flows over FDCAN to the CPU SoM. Configuration happens via I2C. The onboard MCU on the Peripheral SoM handles BME680's native I2C interface and packages data into standardized CAN messages. The CPU SoM receives clean, formatted data—it doesn't need to know BME680-specific details.

Maintain Power Discipline: The environmental sensor draws ~50mA. The 4-20mA output module might sink up to 100mA (20mA × 4 channels plus overhead). The PoE Power SoM Class 4 provides 500mA on the 5V rail—plenty of headroom. But we document power consumption for each module so our engineering team can verify budgets for future product variations.

Implement Standard Blocks: Even though this is a specialized industrial product, it has the same five connector blocks as every other vBus module: Power, Status, Enable, Communication, Programming. No shortcuts, no "we don't need that for this application" exceptions.

Step 4: Carrier PCB Design

The Carrier PCB is where product-specific magic happens, but it's remarkably straightforward:

- Place connectors for each SoM class according to vBus specifications

- Route power distribution from Power SoM to all modules (star topology for low noise)

- Connect Communication Block signals (FDCAN bus, I2C bus, shared interrupt lines)

- Add external interfaces (terminal blocks for 4-20mA outputs, RJ45 for Modbus)

- Include mounting holes and mechanical features for the enclosure

Because the SoM interfaces are standardized, most of the routing follows proven patterns. We have Carrier PCB templates for common configurations that can be adapted in days rather than weeks.

Step 5: Validation and Testing

Here's where vBus design really pays dividends:

Module-Level Testing: Each SoM is tested independently:

- Power SoM: Load testing, efficiency measurement, PoE compliance

- Sensor Peripheral: Calibration, I2C communication, CAN message formatting

- Industrial I/O Peripheral: Output accuracy, isolation testing, loop load response

- Communication SoM: Modbus protocol compliance, RS-485 signal integrity

- CPU SoM: Boot sequence, operating system, application software

System Integration: Because interfaces are known-good, integration is often anticlimactic—it just works. Time spent troubleshooting weird interface issues? Minimal. Time spent on application logic and value-added features? Maximized.

Regression Testing: When we update one module (say, releasing Power SoM Class 4 rev 2 with improved efficiency), we can test it with existing Carrier boards and other modules. Interface compatibility is guaranteed by vBus compliance.

The "Aha!" Moment: When Complexity Becomes Simplicity

Remember my initial anxiety about designing everything to a bus spec? Here's what I didn't understand then but see clearly now: constraints breed creativity within boundaries.

When you remove the decision paralysis of "how should we connect these components?" and replace it with "we connect via vBus," you free mental bandwidth for the problems that actually matter:

- How do we squeeze the best sensor performance from this chipset?

- What's the optimal power architecture for this use case?

- How do we make the firmware robust and maintainable?

It's the same reason professional chefs actually prefer working within ingredient constraints, or why Twitter's 280-character limit forced people to write more clearly. The constraint doesn't stifle—it focuses.

Unexpected Benefits

Beyond the obvious advantages (faster design cycles, reusable modules, parallel development), we've discovered several unexpected benefits:

Product Flexibility: Our customers can configure products to their specific needs. A basic environmental monitor becomes an advanced multi-sensor system simply by adding more Peripheral SoMs. We can offer product tiers (Basic, Pro, Enterprise) without maintaining completely different hardware platforms.

Incremental Improvement: When we develop a better Class 1 Peripheral SoM with a newer sensor, all existing products using that class can benefit. We can offer upgrade paths to customers, and our own product line improves across the board.

Knowledge Transfer: New engineers onboard faster because the architecture is consistent. Learn vBus once, apply it everywhere. Documentation, training materials, debugging techniques—all reusable.

Supply Chain Resilience: If a component on a Power SoM goes end-of-life, we redesign just that module. Products using it? Unaffected except for the module swap. No cascading redesigns across our entire product portfolio.

Rapid Product Development: When market research identifies a new opportunity, we can often respond in weeks instead of months by composing existing modules with a new Carrier board design.

Design Philosophy: The Three Principles

Through this journey, three core principles have emerged that guide every hardware decision:

1. "vBus First, Features Second"

When evaluating a new product idea, we start by asking "how does this fit into vBus?" not "what features do we want?" This flips traditional product development on its head, but it ensures ecosystem coherence.

Example: During product planning for a multi-channel data logger, the initial specification called for 8 analog inputs. Our first question wasn't "which ADC should we use?" but rather "does this need a new Peripheral SoM class, or can Class 1 be extended?" We determined Class 1 could accommodate it with a variant that emphasized analog capability over digital I/O.

2. "Classify, Don't Customize"

Whenever a product requirement seems unique, we resist the urge to create a one-off custom module. Instead, we ask "is this unique enough to justify a new class?" If yes, we create a new class that might benefit future products. If no, we adapt an existing class or use a combination of modules.

This prevents classification explosion (where we'd have 47 subtly different Power SoMs) while still providing flexibility for diverse product applications.

3. "The Carrier is the Canvas"

SoMs are the paint colors; the Carrier PCB is where artistry happens. We keep SoMs as generic and reusable as possible, pushing product-specific features to the Carrier board. Unusual connector? Put it on the Carrier. Custom mechanical interface? Carrier. Weird voltage level translator? Carrier.

This keeps the module library clean and focused while still enabling infinite product variations.

Real-World Impact: The Numbers

After two years of vBus-disciplined design, the metrics speak for themselves:

- Time to market: 40-60% reduction for new products (leveraging existing modules)

- Design iterations: Dropped from average 3 revisions to 1.5 (interfaces are proven, focus on application layer)

- Cross-product part commonality: 65% of components reused across product lines

- Manufacturing setup time: 50% reduction (standardized assembly processes)

- Field service efficiency: 70% faster repairs (swap modules, done)

- Product portfolio expansion: Launched 12 product variants in 18 months using module combinations

But perhaps the most compelling evidence is qualitative: engineering teams who initially resisted the constraints now actively evangelize the approach. Once you experience the simplicity on the other side of compliance, there's no going back.

Conclusion: Embrace the Spec

Designing hardware to a bus specification—truly committing to it, not just paying lip service—is one of the most powerful architectural decisions we've made at Hoomanely. What looked like complexity was actually the path to simplicity. What felt like constraints were actually accelerators.

The vBus ecosystem, with its classification system and modular building blocks, has transformed how we think about product development. We've moved from "design each product from scratch" to "compose products from validated modules." The result is faster, more reliable, more maintainable hardware that scales from prototypes to production without the typical redesign pain.

For product companies considering a modular architecture, my advice is simple: commit fully. Half-measures—where you mostly follow the spec except for those few convenient shortcuts—undermine the entire value proposition. The magic happens when every product uses the same rules, when every module is a first-class ecosystem citizen, when the spec is sacred.

Because here's the secret: the spec isn't the boss. The spec is the foundation. And on a solid foundation, you can build anything.