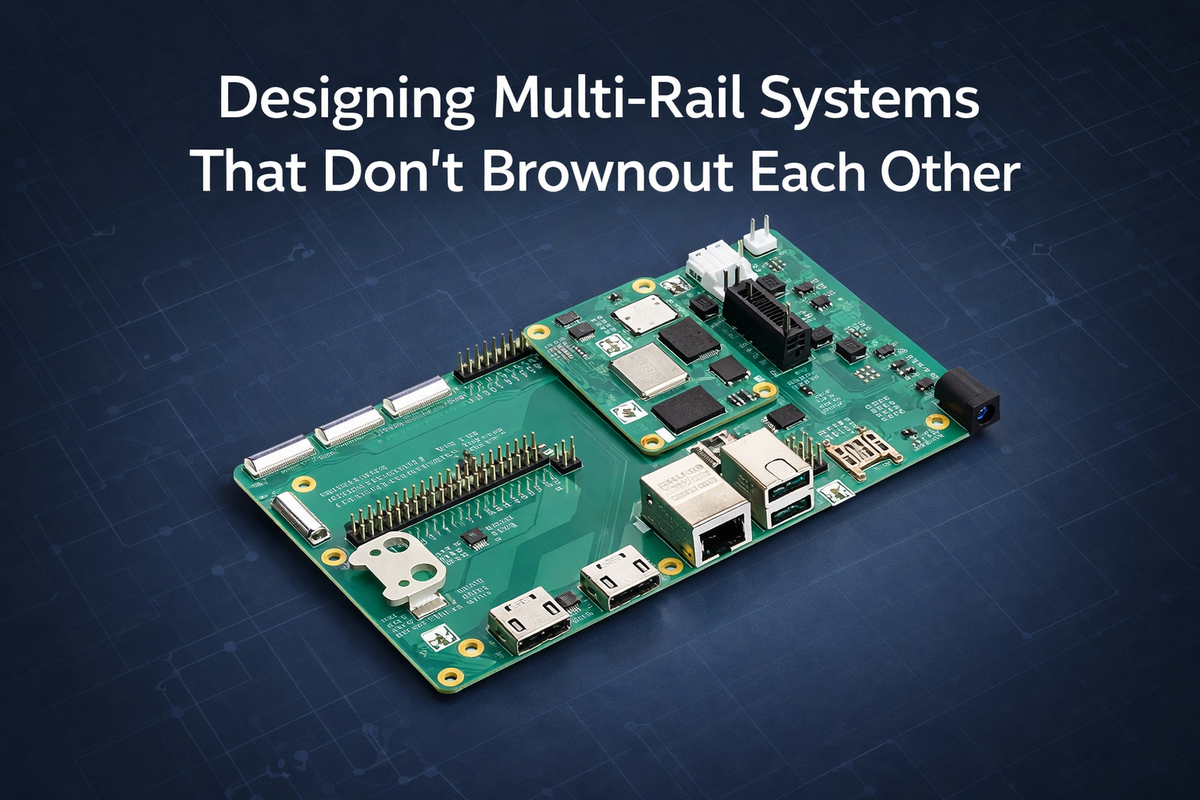

Designing Multi-Rail Systems That Don’t Brownout Each Other

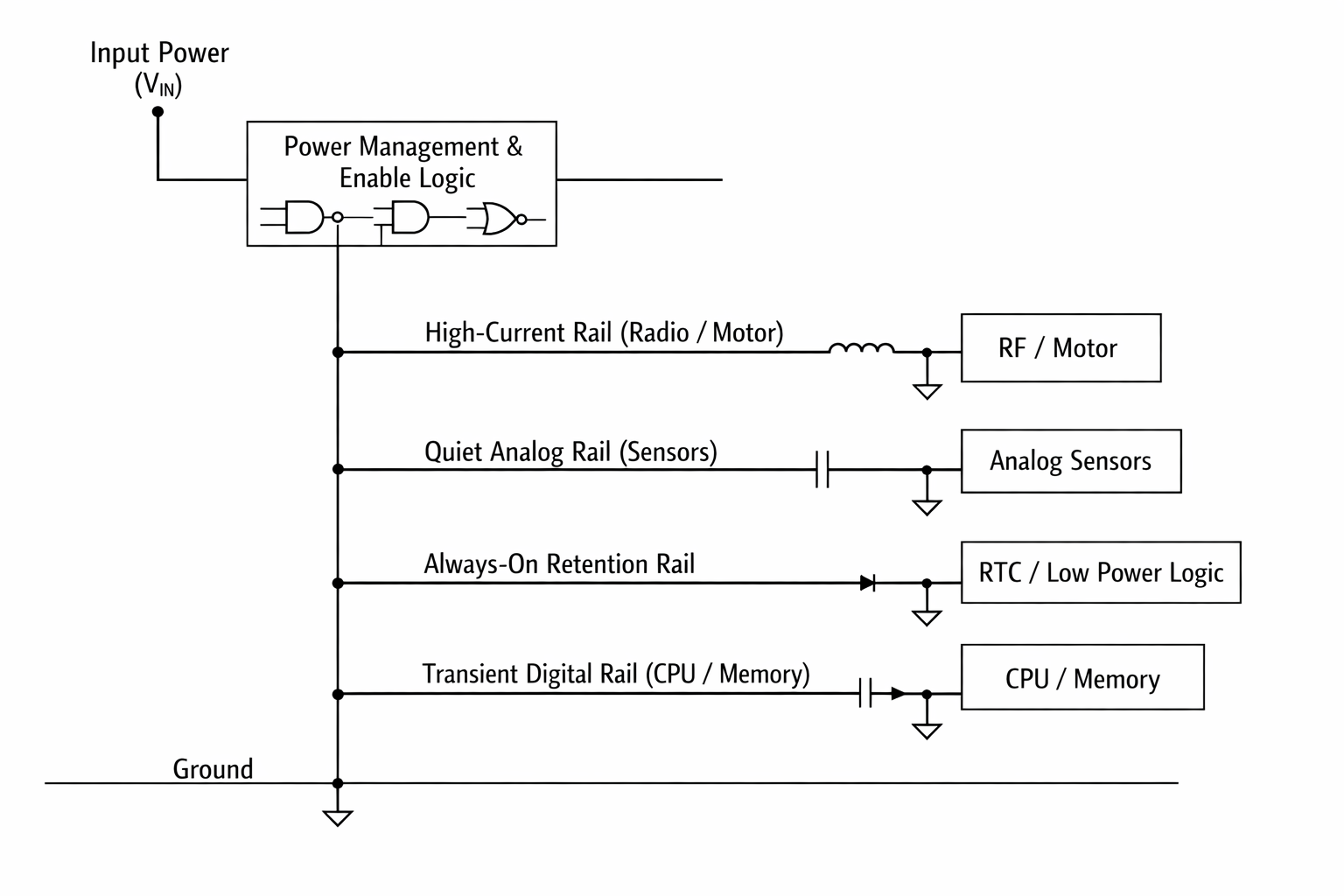

Most modern boards are not powered by a single supply. They are ecosystems of rails: high-current domains for motors or radios, quiet domains for sensors, always-on islands for state retention, and transient-heavy rails that only exist during specific modes.

On paper, these rails look independent. In reality, they are tightly coupled—through copper, silicon, time, and assumptions.

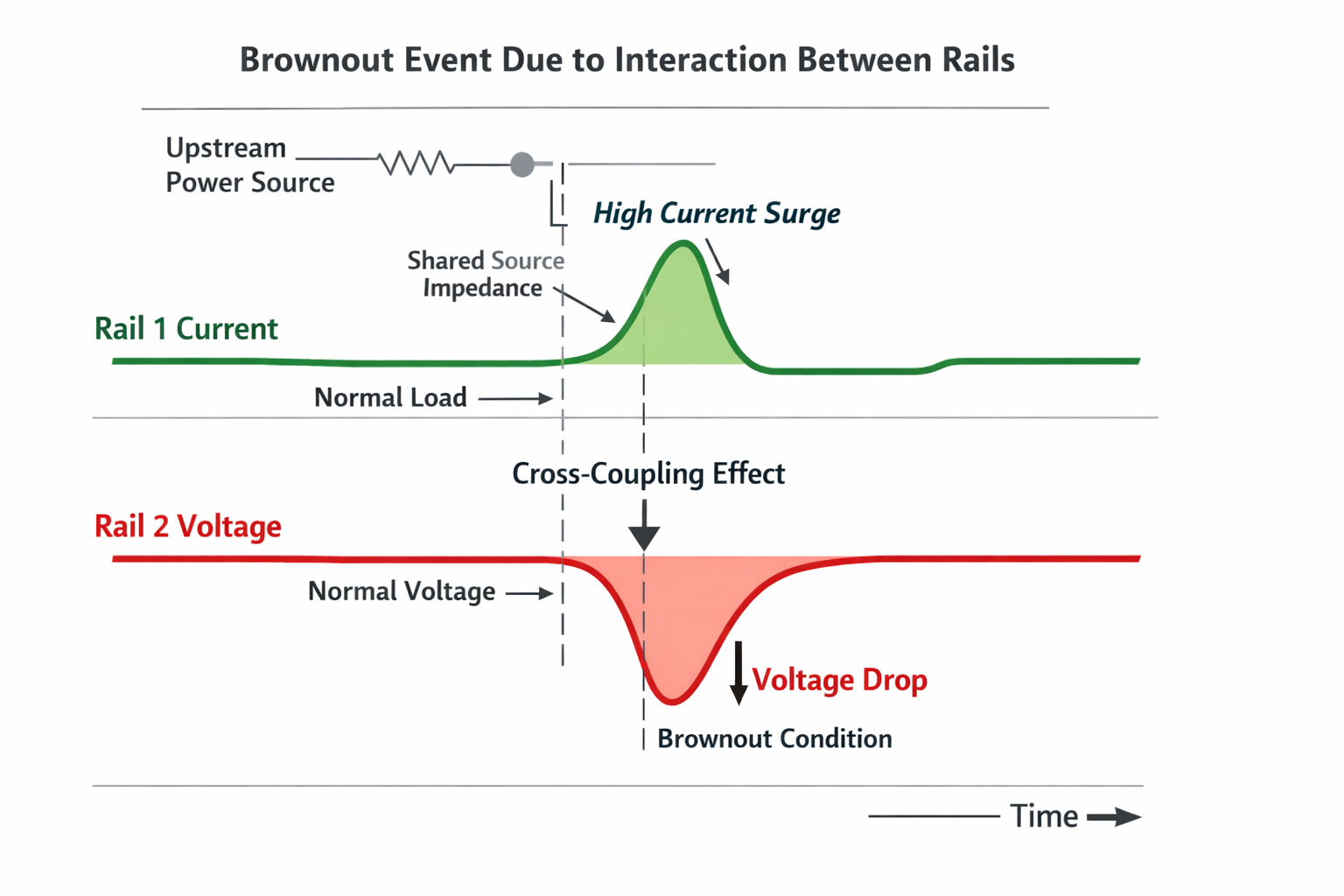

Brownouts rarely come from a single rail collapsing in isolation. They come from interaction. One rail surges, another dips. One domain wakes aggressively, another hasn’t settled. One feature turns on at the wrong moment, and a system that “meets spec” resets anyway.

At Hoomanely, we’ve learned that designing multi-rail systems is less about choosing regulators and more about managing relationships. Rails don’t fail alone; they drag each other down unless you design them not to.

This article explores how to build multi-rail systems that remain stable under real usage—when features overlap, loads change dynamically, and timing is imperfect.

Brownouts Are System Events, Not Power Events

It’s tempting to debug brownouts rail by rail:

- Measure the dip

- Increase capacitance

- Slow the ramp

- Try again

Sometimes that works. Often it doesn’t.

That’s because a brownout is rarely caused by a rail being undersized in isolation. It’s caused by how rails interact under concurrency.

Common patterns include:

- A high-current rail surging and pulling down a shared upstream source

- A digital rail toggling aggressively while an analog rail is still settling

- A late-enabling domain triggering logic before references are valid

- Multiple “safe” loads turning on simultaneously

Seen this way, a brownout is not a failure of power delivery. It is a failure of coordination.

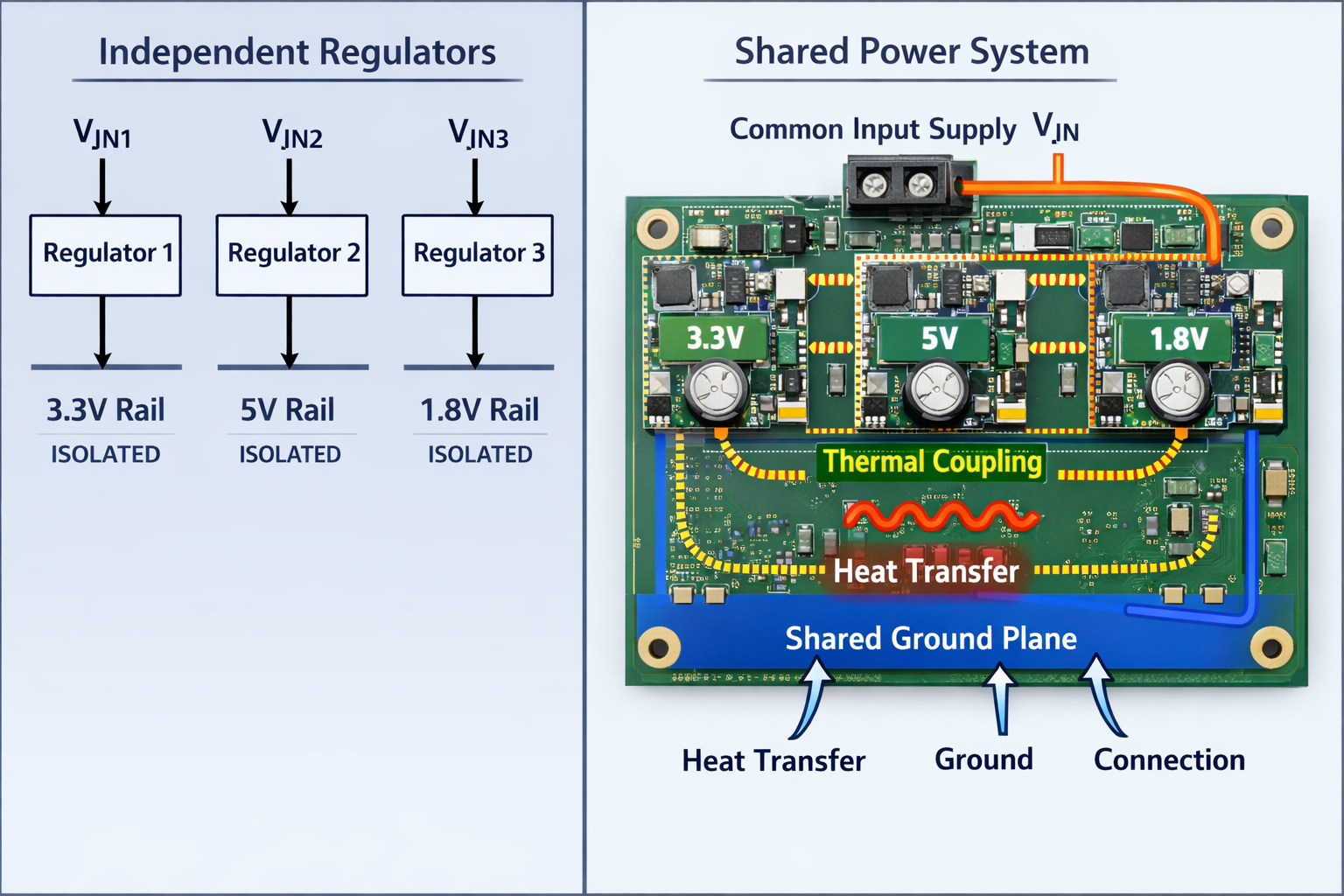

The Myth of Independent Rails

Schematics encourage a comforting illusion: each rail has its own regulator, its own decoupling, its own name. Therefore, each rail is independent.

Physically, they are not.

Rails share:

- Upstream sources

- Ground return paths

- Enable logic

- Thermal environments

- Time

A surge on one rail affects upstream impedance. A temperature rise changes regulator behaviour. A delayed enable alters load alignment.

Designing multi-rail systems that don’t brownout each other requires acknowledging this coupling—and then deciding where it is allowed to exist.

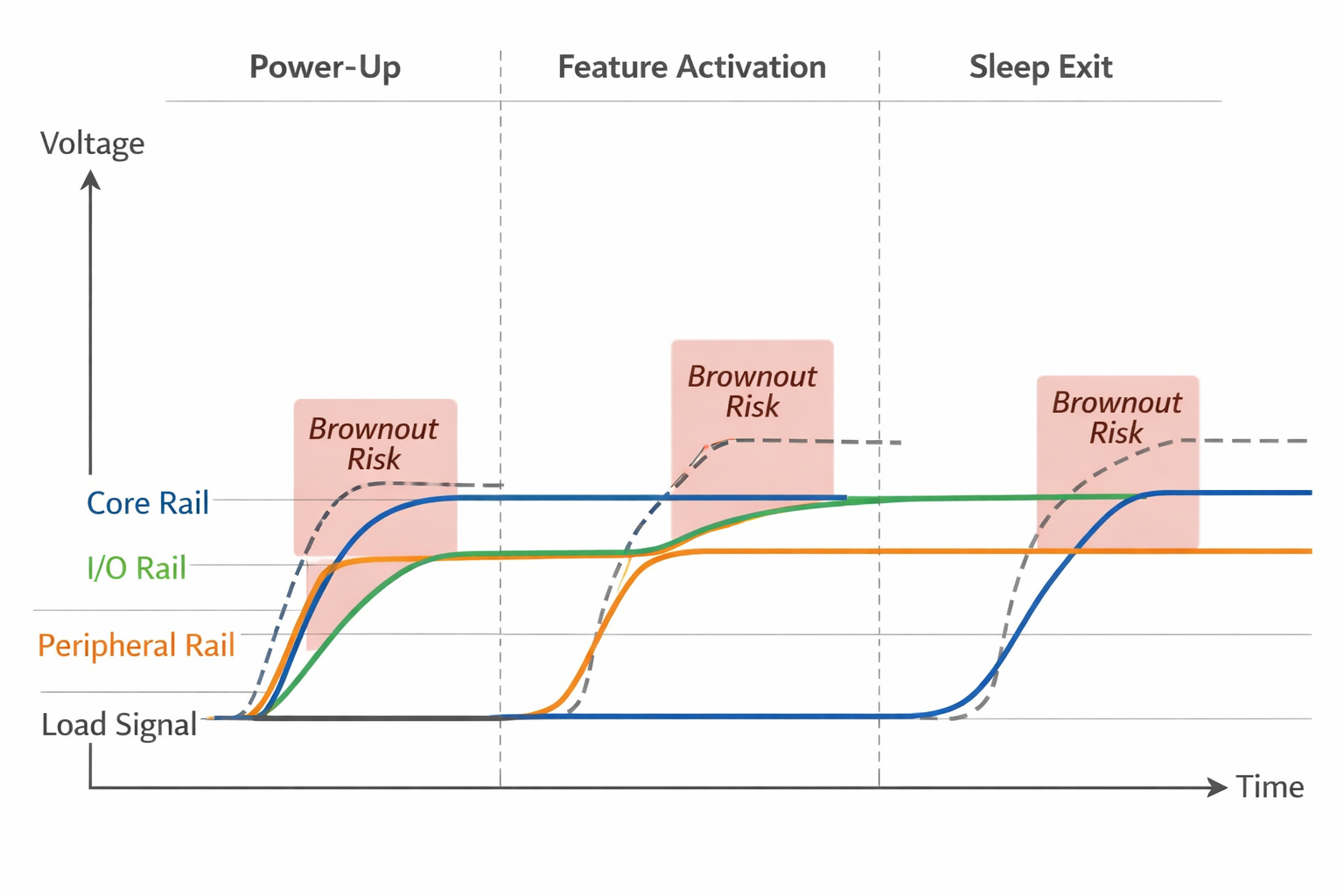

Power Is Temporal, Not Just Electrical

One of the most underappreciated aspects of power design is time.

Most rail specifications focus on steady-state behavior:

- Nominal voltage

- Maximum current

- Ripple

Brownouts almost never happen at steady state. They happen during transitions:

- Power-up

- Mode changes

- Feature activation

- Sleep exit

During these moments:

- Loads appear suddenly

- Control loops haven’t settled

- Capacitors are empty

- Firmware assumptions are premature

A resilient system treats time as a first-class design dimension. It asks:

- Which rails must be stable before others wake?

- Which loads are allowed to overlap?

- Which transitions are safe to compress—and which are not?

If timing is not designed, it will be discovered painfully.

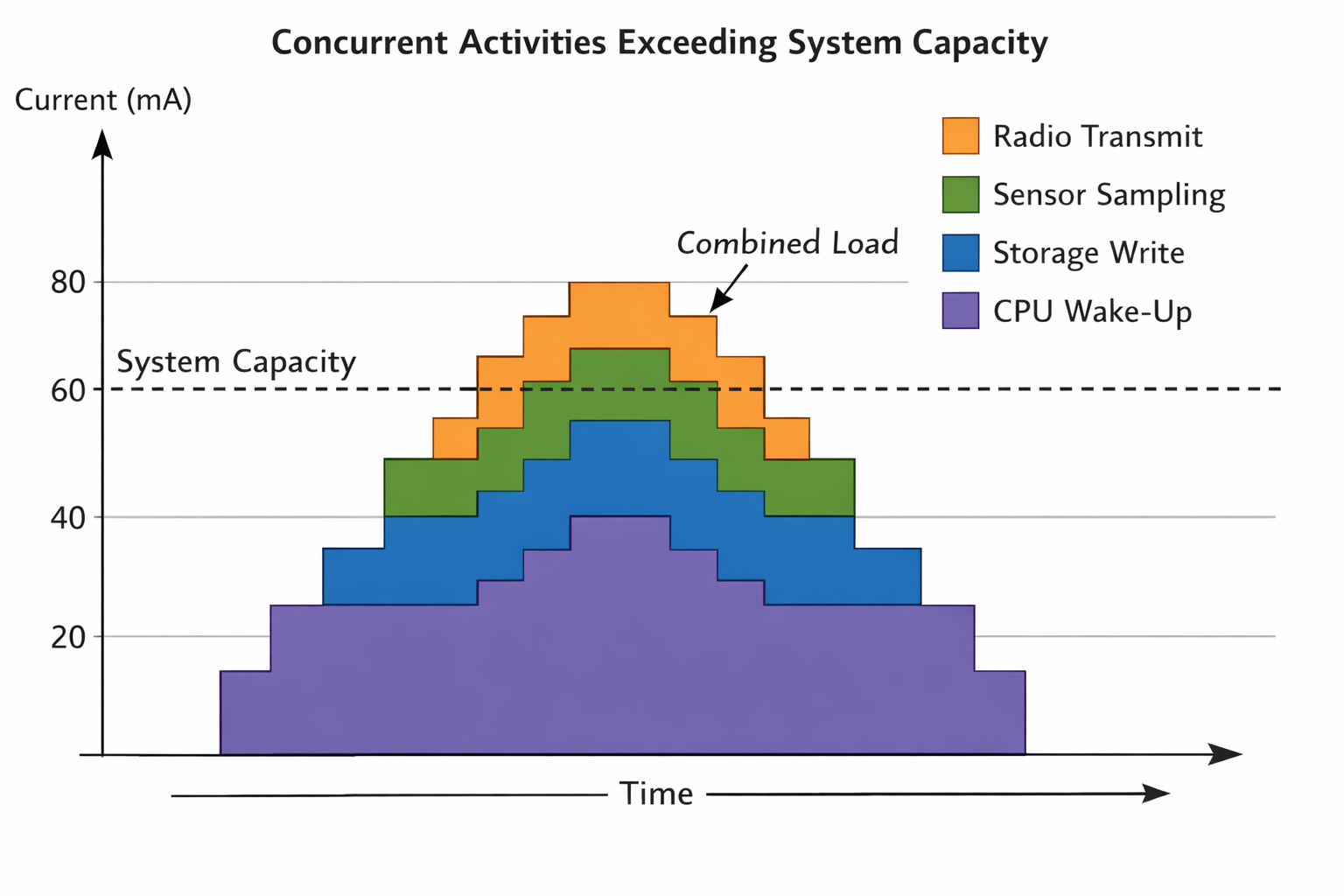

Load Concurrency Is the Real Enemy

Many designs validate rails independently under worst-case load. Few validate concurrent worst cases.

In real products, features overlap:

- Radio transmit coincides with sensor sampling

- Motors spin while storage writes

- Displays update while CPUs exit sleep

Each feature is “within budget.” Together, they are not.

Designing multi-rail systems that don’t brownout requires:

- Identifying concurrency groups

- Understanding which features can legally overlap

- Enforcing limits when they cannot

This enforcement should not rely solely on firmware discipline. Hardware must participate—by shaping when and how loads appear.

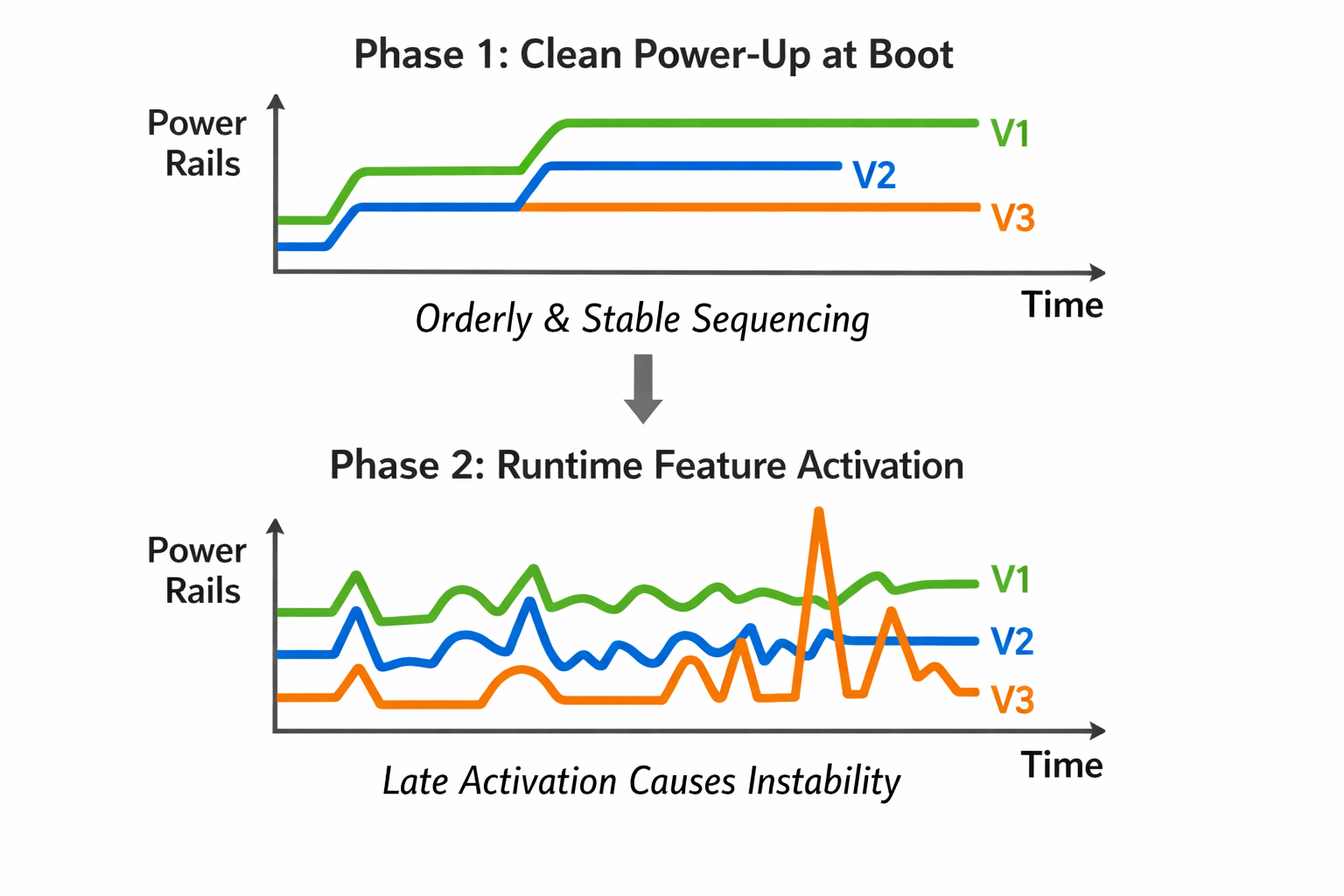

Sequencing Is Not Enough

Power sequencing is often treated as the solution to brownouts: turn things on in the right order and the problem goes away.

Sequencing is necessary—but insufficient.

Why?

- Sequencing only controls initial order

- Brownouts often occur after boot

- Runtime feature activation bypasses boot-time assumptions

A system that sequences perfectly at startup can still collapse during:

- Dynamic feature enable

- Firmware updates

- Recovery cycles

The deeper solution is ongoing coordination, not one-time ordering.

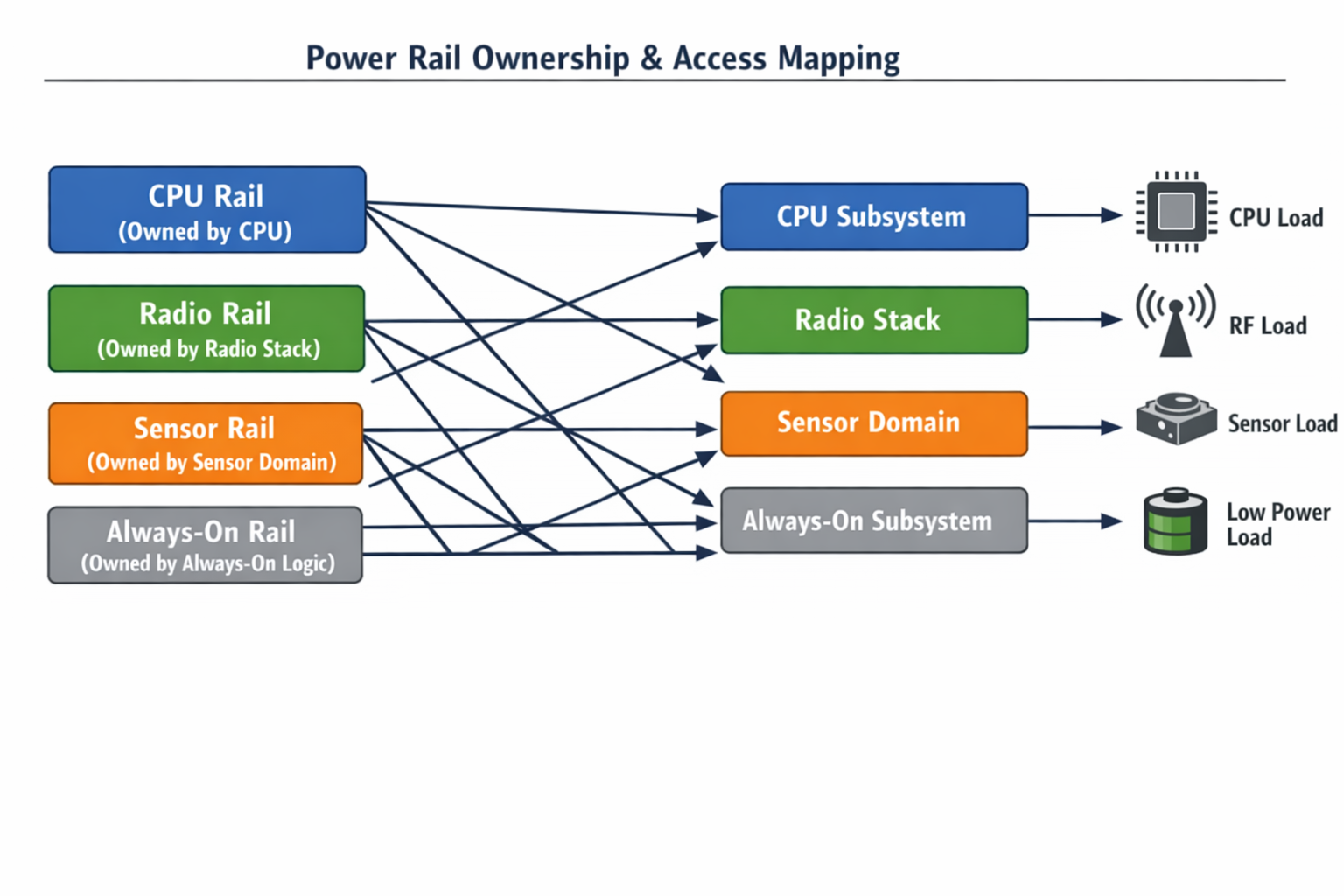

Rails Must Have Clear Ownership

In many systems, no one truly “owns” a rail.

Hardware defines it. Firmware uses it. Features depend on it. But no one is accountable for its behavior under stress.

Clear ownership means:

- Knowing which subsystem is allowed to activate loads

- Knowing which rail can tolerate transients

- Knowing which rails are critical to system survival

When ownership is ambiguous, features compete silently. When ownership is clear, conflicts are designed out—or at least made visible.

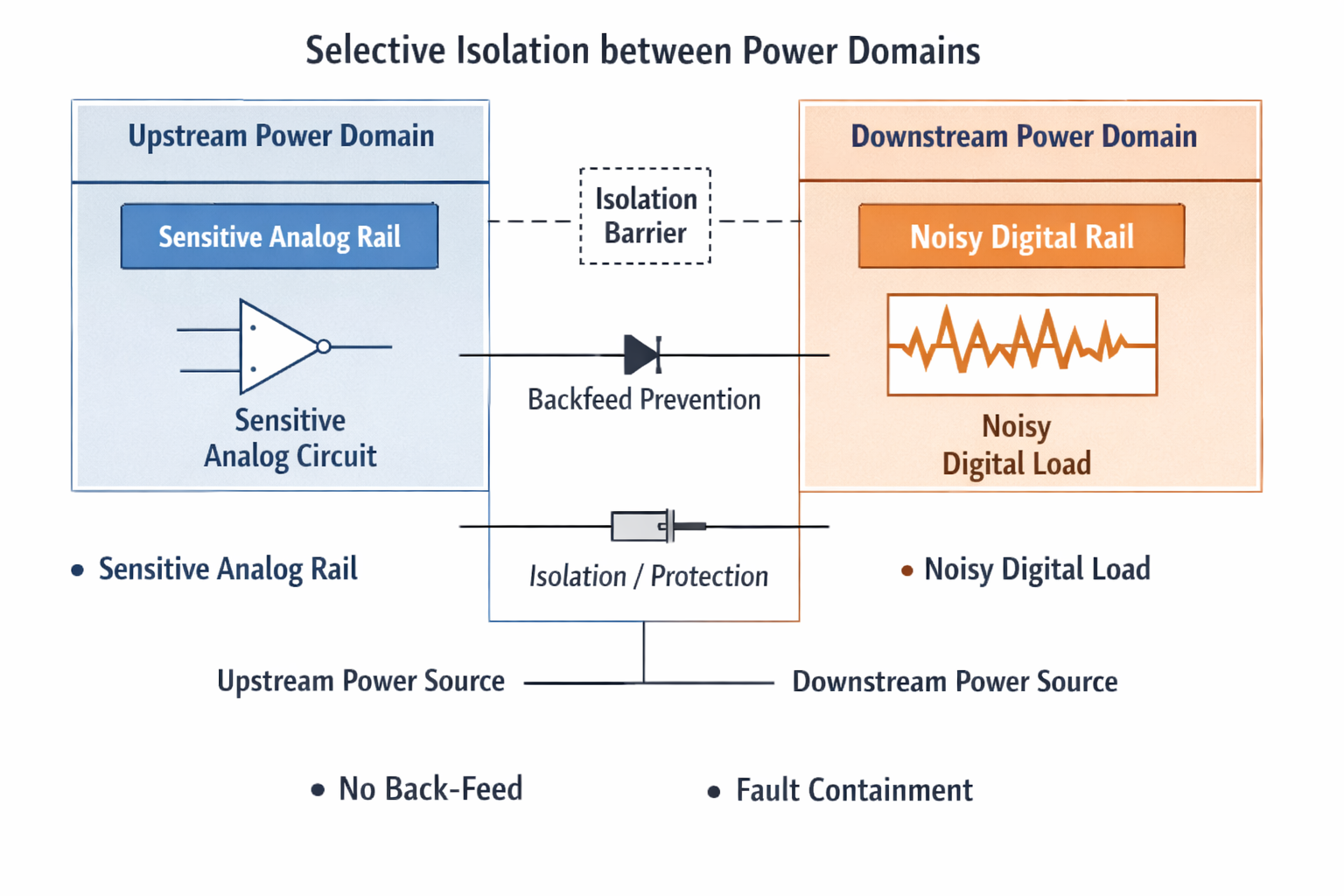

Isolation Is a Stability Tool

One of the most effective ways to prevent rails from brown-outing each other is intentional isolation.

Isolation doesn’t mean total separation. It means deciding:

- Which disturbances are allowed to propagate

- Which must be absorbed locally

- Which must be blocked entirely

This can include:

- Separating noisy loads from sensitive domains

- Preventing downstream rails from back-feeding upstream sources

- Ensuring that failure in one domain cannot reset another

Isolation turns uncontrolled coupling into designed interaction.

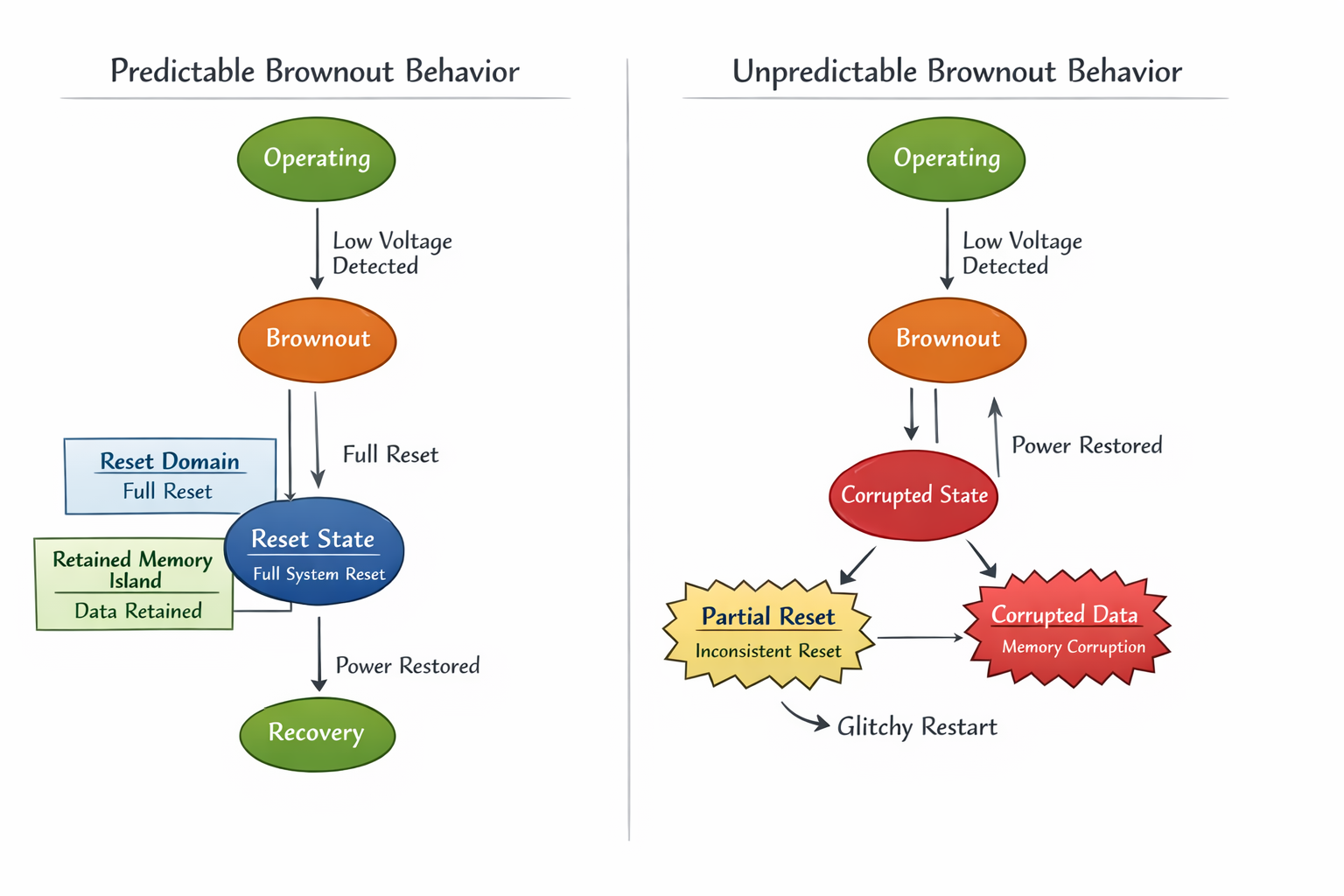

Brownout Behavior Should Be Predictable

Even well-designed systems will experience brownouts under extreme conditions. The goal is not to eliminate them entirely, but to make their behavior predictable and recoverable.

Predictable brownout behavior means:

- Known reset domains

- Known retention behavior

- Known recovery paths

Unpredictable behavior—partial resets, corrupted state, locked interfaces—is far more damaging than a clean reset.

Designing for predictability requires thinking beyond voltage thresholds. It requires deciding what survives when power is marginal.

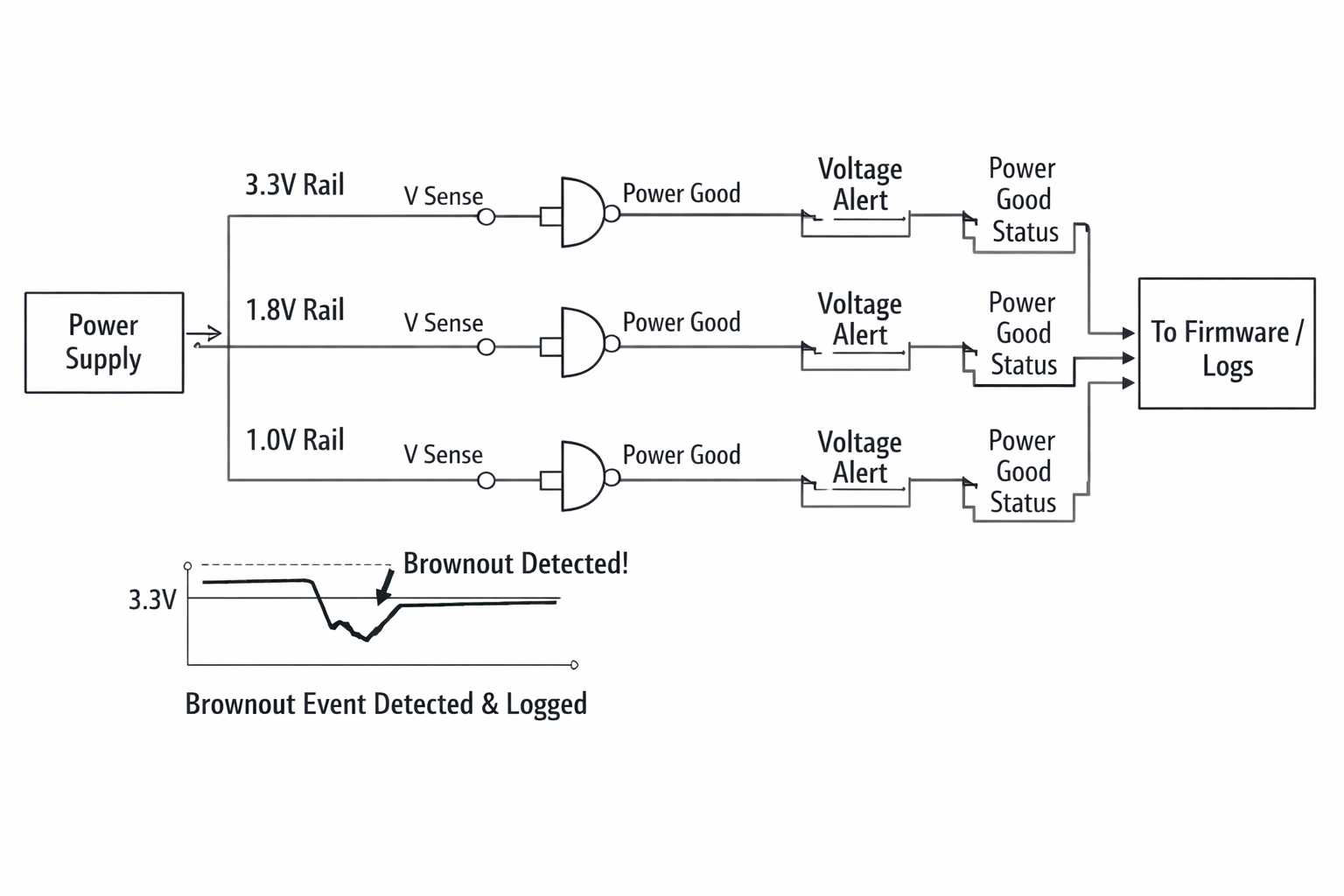

Observability Changes Everything

Multi-rail systems that brownout silently are nightmares to debug.

When rails are observable—electrically and logically—patterns emerge:

- Which rail dips first

- Which feature triggered the event

- Whether the event was upstream or local

This observability does not need to be complex. Even simple indicators and measurements, placed intentionally, can turn a mysterious reset into a diagnosable event.

Designing observability into power domains transforms brownouts from ghosts into data.

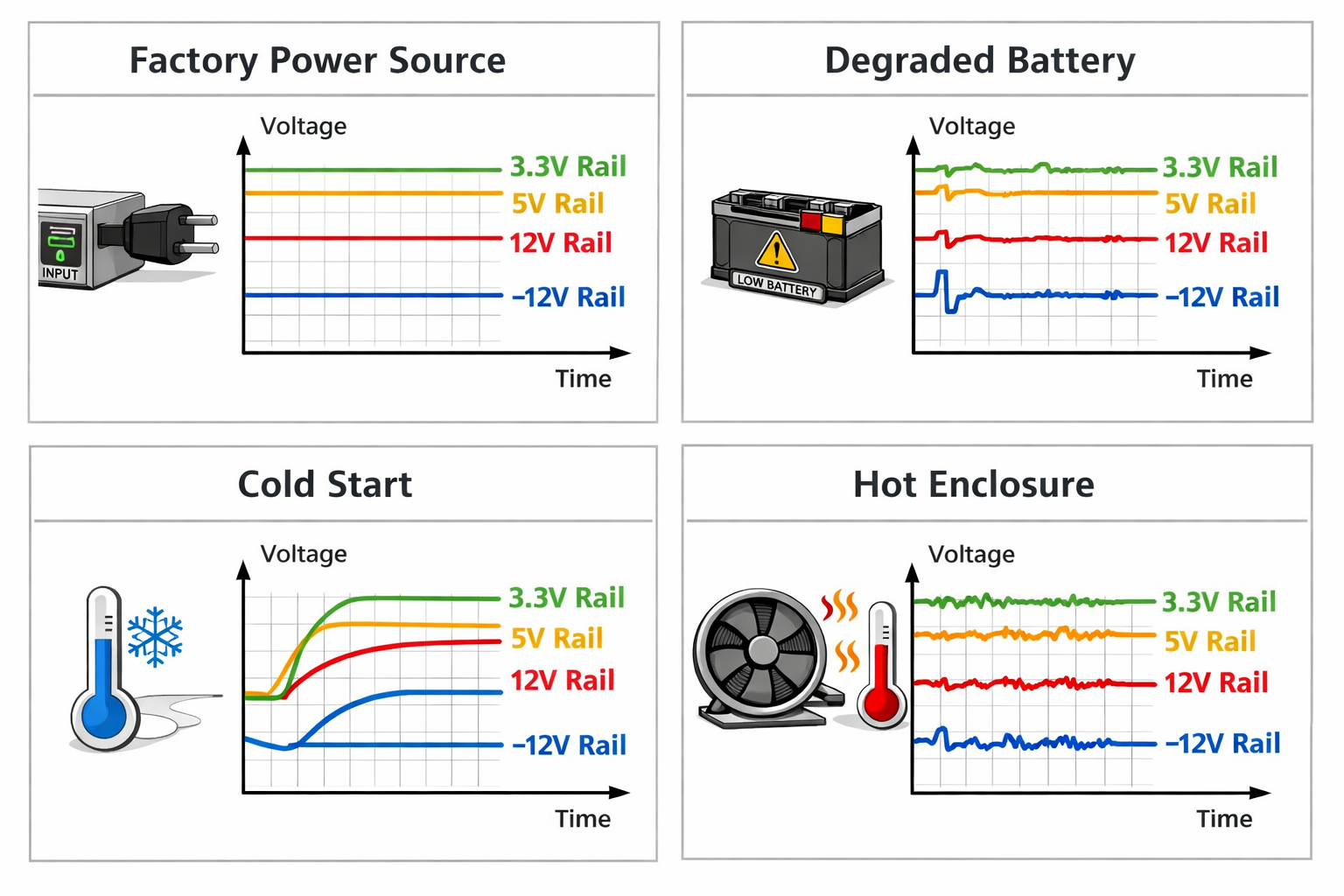

Manufacturing and Field Reality

Brownouts don’t just appear in the lab. They appear:

- On factory lines with shared power

- In the field with degraded batteries

- In cold starts and hot enclosures

- After months of aging

A system that barely survives ideal conditions will fail unpredictably elsewhere.

Designing multi-rail systems that don’t brownout each other means validating behavior across:

- Load combinations

- Environmental extremes

- Aging components

- Imperfect sources

This validation is architectural, not procedural. If the system is designed to be tolerant, validation confirms it. If not, validation becomes whack-a-mole.

Stability Is a System Property

It’s tempting to assign brownouts to “the power team” or “the regulator choice.” In reality, stability emerges from the interaction of:

- Power architecture

- Feature design

- Firmware behavior

- Mechanical and thermal constraints

No single decision fixes brownouts. But many small, intentional decisions prevent them.

At Hoomanely, we treat multi-rail stability as a platform feature. It’s not something you bolt on. It’s something you design into the system from the beginning—by acknowledging coupling, respecting time, and enforcing coordination.

A multi-rail system that doesn’t brownout under real usage doesn’t just stay on.

It earns the right to scale—because it understands its own limits.