Designing vBus: A Universal Bus Architecture for Modular Embedded Systems

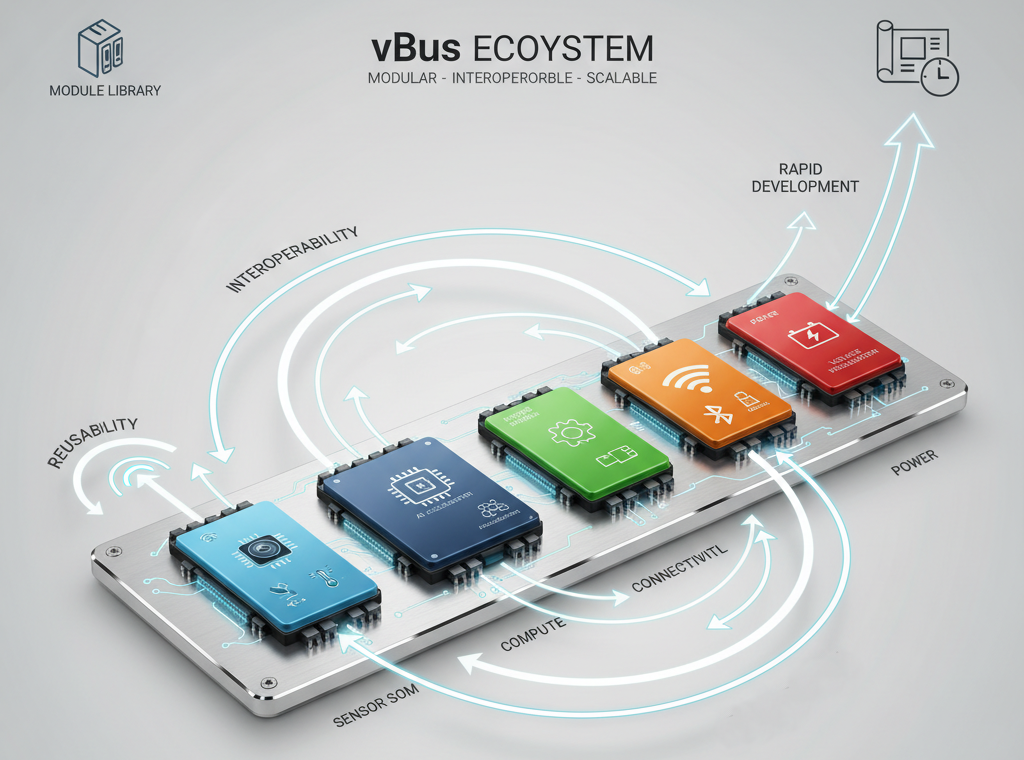

In the world of embedded systems development, one of the most persistent challenges is creating hardware that's both flexible and standardized. At Hoomanely, we've tackled this challenge head-on by developing vBus—a universal communication bus architecture that serves as the backbone for all our product lines. Think of it as the USB of our ecosystem, but purpose-built for System-on-Module (SOM) interconnectivity.

The concept is elegantly simple: every functional module, regardless of its purpose or complexity, communicates with the rest of the system through a standardized interface. Whether it's a sensor module, a processing unit, or a power management board, they all speak the same language through vBus. However, as with most engineering challenges, the devil is in the details.

The Challenge: One Interface to Rule Them All

Creating a truly universal communication bus isn't just about picking a connector and defining some pin assignments. It's a multidimensional problem that requires careful consideration of mechanical, electrical, and logical constraints. Let me walk you through the four major challenges we encountered—and how we're addressing them.

1. Connector Selection: The Goldilocks Problem

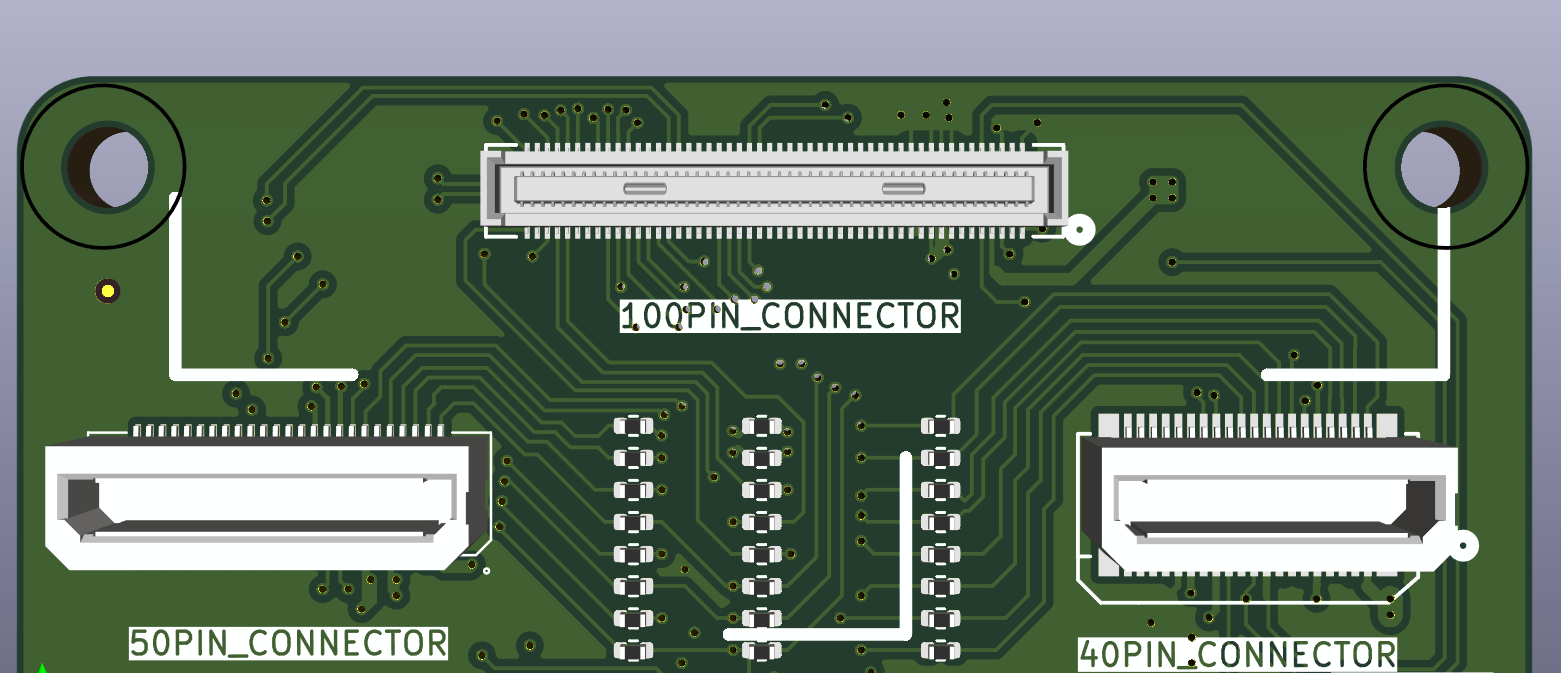

The first challenge might seem straightforward: choose a connector. But when your SOMs range from tiny sensor boards measuring just a few square centimeters to larger processing modules with extensive I/O requirements, finding a connector that works for everyone becomes a complex optimization problem.

The constraint: A small sensor SOM might have limited PCB real estate, where a large, high-pin-count connector would dominate the board and potentially cost more than the components it connects. Conversely, a minimal connector on a feature-rich module would create a bottleneck, forcing multiple modules to be daisy-chained or requiring custom breakout boards.

Our approach involves:

- Defining a family of connectors rather than a single solution—think of it as S, M, L, and XL variants

- Establishing a hierarchical pinout where the most critical signals occupy consistent positions across all connector sizes

- Selecting connector types with high pin density while maintaining reliable manufacturability

- Considering both vertical and horizontal mounting options to accommodate different form factors

The key insight here is that true modularity doesn't mean identical—it means compatible. Our connector strategy allows designers to choose the right tool for the job while maintaining interoperability through careful pinout planning.

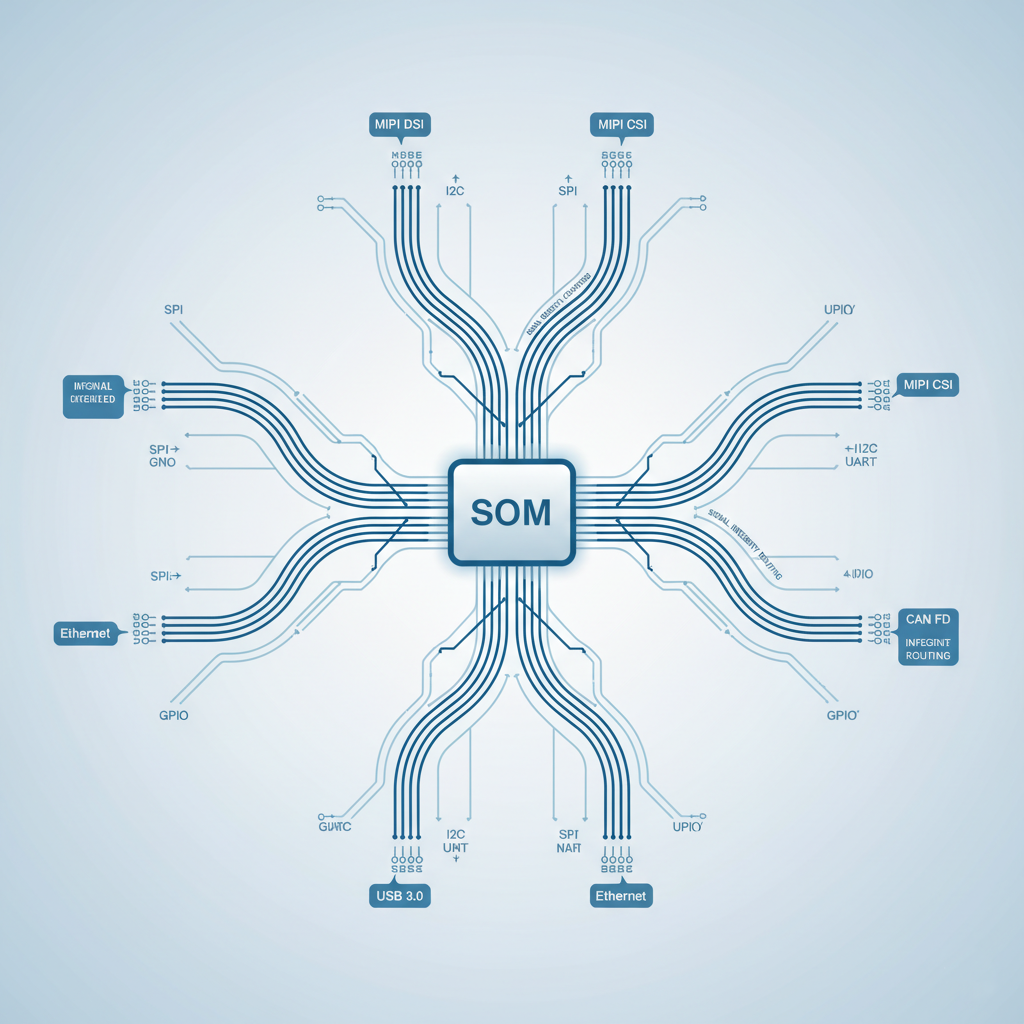

2. Communication Interface Diversity: Speaking Multiple Dialects

Modern SOMs aren't one-size-fits-all, and neither are their communication requirements. A high-speed camera module might need PCIe or high-speed LVDS interfaces for streaming video data at gigabits per second. Meanwhile, a simple temperature sensor might only need I2C running at a few hundred kilohertz. An actuator control module might require high-precision PWM signals with strict timing requirements.

The challenge is threefold:

- Speed diversity: Supporting both multi-gigabit differential pairs and simple GPIO without compromising either

- Protocol variety: Accommodating UART, SPI, I2C, CAN, USB, Ethernet, and specialized protocols like MIPI-CSI or LVDS

- Signal integrity: Maintaining clean signals for high-speed data while keeping the connector and traces cost-effective

Our solution strategy:

- Allocating dedicated lanes for high-speed differential pairs with controlled impedance routing guidelines

- Reserving a pool of configurable pins that can serve multiple protocols through software configuration

- Implementing a signal classification system (power, high-speed data, low-speed control, analog) that guides both pin assignment and PCB layout

- Including sideband communication channels (like I2C) that allow modules to identify themselves and negotiate capabilities

This approach allows a designer to build a minimal sensor node using just the low-speed pins, while another engineer can develop a vision processing module that leverages the high-speed lanes—both using the same fundamental vBus architecture.

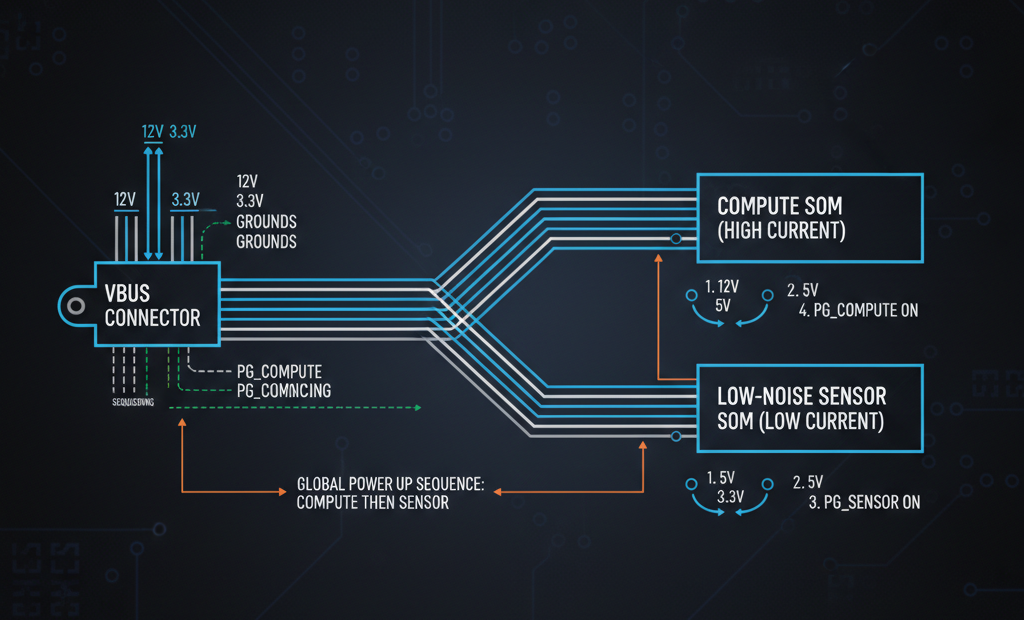

3. Power Distribution: More Than Just Voltage Rails

Power delivery in a modular system is remarkably complex. It's not just about providing 3.3V, 5V, and 12V rails—it's about doing so efficiently, safely, and flexibly across diverse use cases.

Consider these scenarios:

- A processing SOM might need 5V at 3A, 3.3V at 500mA, and 1.8V at 200mA

- A motor control module might require 12V at 5A with protection against back-EMF

- A sensor board might run on 3.3V at just 50mA but need ultra-low noise for analog measurements

The challenges include:

- Current capacity: Connector pins have maximum current ratings. Running 5A through a single pin designed for 1A creates heating issues and voltage drop

- Pin allocation: More power pins mean fewer signal pins, creating tough trade-offs

- Voltage selection: Should we provide raw voltages and let each SOM regulate down, or provide multiple regulated rails?

- Ground integrity: Adequate ground pins are essential for signal integrity and safety, but they compete for valuable connector real estate

Our power strategy involves:

- Dedicating multiple parallel pins for high-current rails, effectively multiplying the current capacity

- Providing a mix of raw battery voltage (for power-hungry components) and regulated common voltages (for ease of use)

- Implementing a separate ground pin allocation strategy that ensures low-impedance return paths

- Including power-good and enable signals that allow for sequencing and power management

- Documenting maximum current budgets per rail and providing design guidelines for SOM power consumption

The goal is to make power distribution robust enough for demanding applications while remaining simple for basic modules.

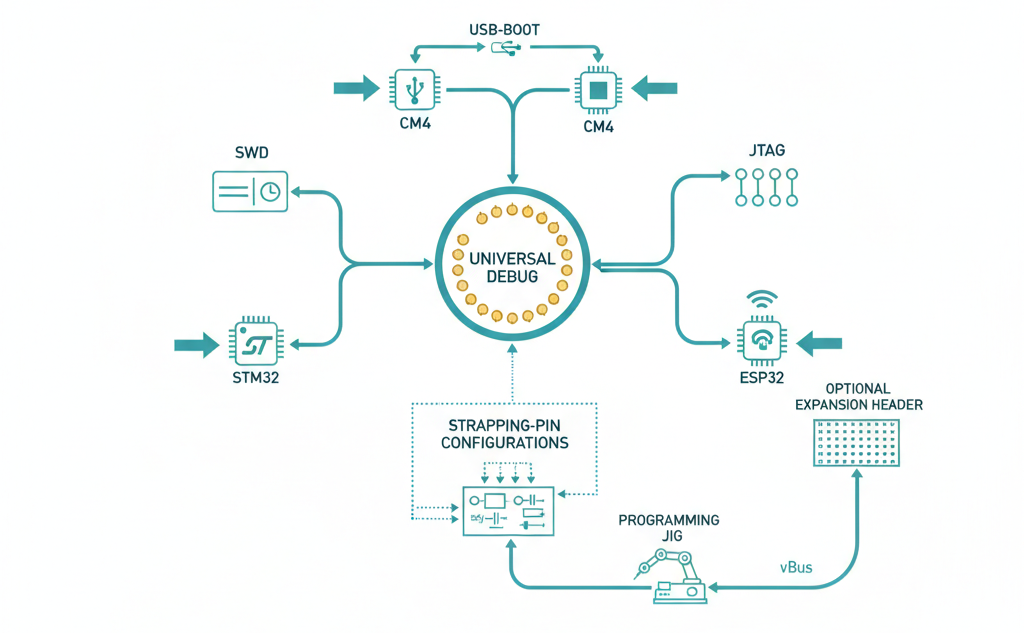

4. Debug and Boot Infrastructure: The Hidden Complexity

Here's a challenge that often gets overlooked until late in the development cycle: every microcontroller and processor has its own requirements for programming, debugging, and boot configuration. An STM32 uses SWD with two pins. An ESP32 needs specific strapping pins during boot. A Raspberry Pi compute module requires USB boot modes. An NXP i.MX processor might need JTAG for debugging.

The complications:

- Different architectures use incompatible debug protocols (SWD, JTAG, cJTAG, etc.)

- Boot mode selection often requires pulling specific pins high or low during power-up

- Some processors need dedicated debug connectors, while others can share pins

- Pin count limitations force difficult prioritization decisions

Our approach includes:

- Reserving a debug pin group that can support multiple protocols through careful selection (e.g., pins that can function as either SWD or JTAG)

- Defining a boot configuration standard that uses a minimal pin set compatible across multiple architectures

- Providing optional expansion headers on SOMs for architecture-specific debugging needs

- Including I2C-based GPIO expanders on the bus that can be used for remote boot mode configuration

- Creating programming jigs that can access the vBus connector directly, eliminating the need for per-module debug headers

This standardization dramatically reduces the learning curve when moving between different SOM types and enables common tooling across the entire product ecosystem.

The Bigger Picture: Why Universal Interfaces Matter

The vBus architecture isn't just an engineering exercise—it's a business and development velocity enabler. By establishing this common foundation, we achieve:

Faster development cycles: Engineers can mix and match modules without redesigning interconnects for each project, reducing time-to-market significantly.

Cost optimization: Standardized connectors and interfaces allow for volume purchasing and reduced SKU proliferation. A single backplane design can host multiple SOM configurations.

Future-proofing: As we develop new SOMs, they automatically integrate with existing carrier boards and accessories, protecting our ecosystem investment.

Easier testing and validation: Common interfaces mean common test fixtures and procedures, reducing QA overhead.

Customer flexibility: End-users can upgrade or reconfigure systems by swapping modules without hardware redesign.

Conclusion

Designing the vBus architecture has been an exercise in systematic constraint resolution. Each challenge—connector selection, interface diversity, power distribution, and debug infrastructure—requires balancing competing requirements while maintaining the core promise of universal modularity.

The result is an architecture that doesn't try to be everything to everyone with a single massive connector, but instead provides a flexible framework that scales from simple sensor nodes to complex processing systems. It's a testament to the principle that good standardization isn't about rigidity—it's about creating enough structure to ensure compatibility while leaving room for innovation within that framework.

As we continue to expand our product line, vBus evolves with it, incorporating lessons learned and adapting to new requirements. But the fundamental principle remains: every module, one language, endless possibilities.