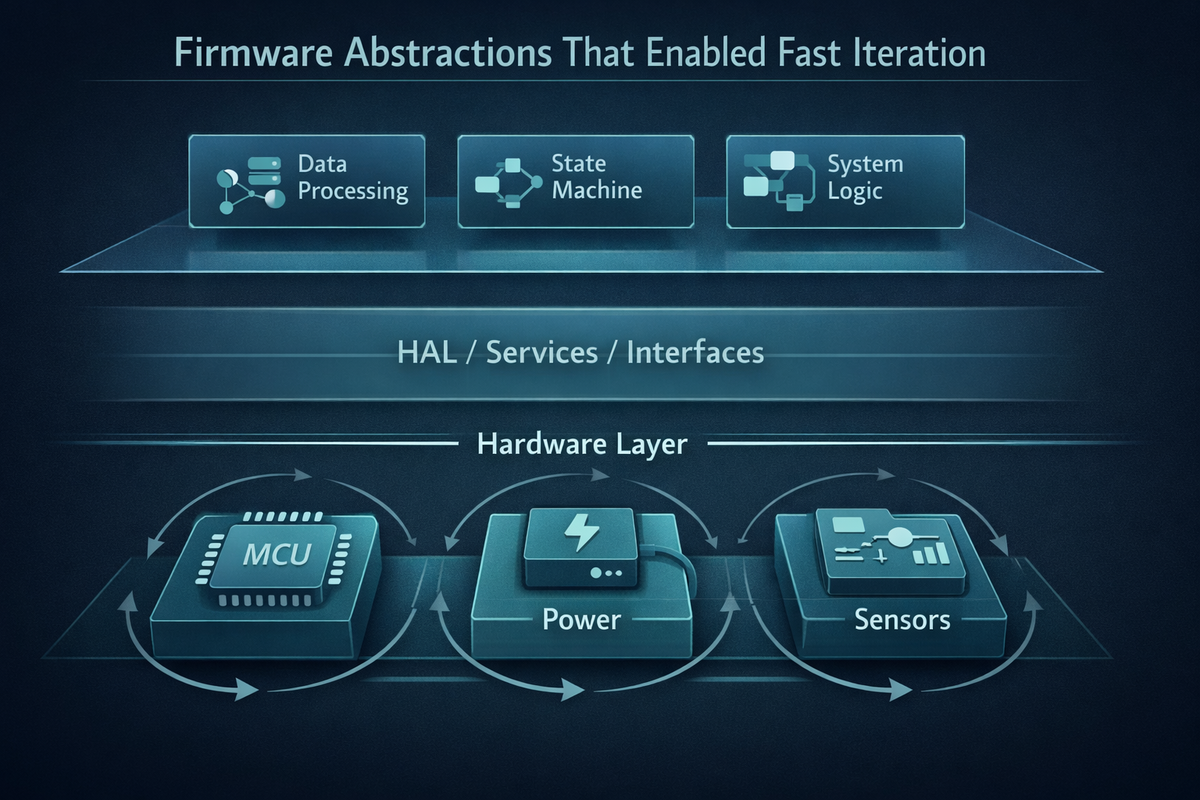

Firmware Abstractions That Enabled Fast Iteration

Introduction: Velocity Without Fragility

In embedded systems, speed and stability are often framed as opposing forces. Fast iteration is seen as something you do early, before the “real” system exists. Reliability is something you enforce later, once hardware is fixed and features are locked. In practice, this separation is artificial—and costly.

At Hoomanely, iteration speed is not a phase; it is a continuous capability. Our products evolve rapidly at the prototype stage, not through rushed firmware changes, but through carefully designed firmware abstractions that allow change without instability. These abstractions allow us to pre-verify behaviour, simulate hardware boundaries, and adapt to evolving electronics without rewriting core logic.

Firmware abstraction is not about hiding complexity. It is about containing change—ensuring that when something evolves, its impact remains local, predictable, and verifiable. This philosophy has become foundational to how we design, validate, and scale our vBus-based products.

Abstraction as a Product Enabler, Not a Software Pattern

In many embedded projects, abstraction layers are introduced defensively—often late in the lifecycle—once the codebase becomes difficult to manage. We take the opposite approach. Firmware abstraction is treated as product infrastructure, designed alongside hardware and system architecture.

Our goal is simple:

Allow firmware to move at a different speed than hardware, without breaking alignment between the two.

This matters because vBus products are inherently modular. CPU SoMs, power modules, peripherals, and sensors evolve independently. Firmware must accommodate:

- Multiple board revisions

- Alternate components with identical roles

- Changing electrical constraints

- Feature growth without destabilising existing behaviour

Abstraction is what makes that possible.

The Three-Layer Firmware Contract

At the heart of our approach is a deliberate separation of firmware responsibilities into three layers, each with a clear contract.

1. Hardware Access Layer (HAL): Owning the Physics

This layer deals exclusively with electrical reality:

- Register access

- Pin configuration

- Bus transactions

- Timing constraints

- Power sequencing

The HAL knows how a thing works electrically—but not why it exists.

Key characteristics:

- One implementation per hardware variant

- No product logic

- Deterministic behavior

- Testable in isolation

When a sensor changes from I²C to SPI, or a GPIO moves pins, the HAL absorbs the change. Everything above remains untouched.

This is where hardware iteration is isolated.

2. Device and Service Abstractions: Owning Behaviour

Above the HAL sit device-level abstractions:

- Sensors expose calibrated measurements, not registers

- Power systems expose states, limits, and transitions

- Communication stacks expose messages, not frames

These abstractions describe what the system does, not how it does it.

Examples:

- A weight sensor provides stable mass readings

- A power module exposes supply readiness

- A radio provides connectivity state

The implementation may change, but the contract does not.

This layer enables pre-verification. Core firmware logic can be exercised long before final hardware is locked, using mock implementations that respect the same interface.

3. Product Logic: Owning Intent

The top layer expresses product intent:

- When data is captured

- How decisions are made

- How states transition

- How errors are handled

Crucially, this layer has:

- No register knowledge

- No timing assumptions

- No hardware dependencies

It speaks only in terms of services and devices.

This separation is what allows firmware to be validated early, confidently, and repeatedly—even as hardware continues to evolve.

Pre-Verification Through Interface Stability

Fast iteration is only valuable if it is safe. Firmware abstraction allows us to verify behaviour before physical integration.

Simulated Hardware, Real Logic

Because device interfaces are stable, we can:

- Replace real sensors with deterministic mock sources

- Simulate boundary conditions

- Validate state transitions and timing logic

- Exercise rare scenarios without physical setup

This means that when hardware arrives, firmware behavior is already known.

The first power-on is not a discovery moment—it is a confirmation.

Parallel Hardware and Firmware Development

One of the most tangible benefits of abstraction is decoupling schedules.

Hardware teams iterate on:

- Layout density

- Power integrity

- Connector alignment

- Mechanical fit

Firmware teams iterate on:

- Feature behavior

- Data pipelines

- Power policies

- Communication flows

Neither waits on the other.

As long as the interface contract remains intact, both can move independently. When hardware stabilizes, integration becomes a mapping exercise—not a rewrite.

This parallelism compresses development timelines without increasing risk.

Supporting Board Revisions Without Code Fragmentation

Board revisions are inevitable in complex systems. The difference lies in how disruptive they are.

With abstraction:

- Board-specific changes are localized

- Multiple revisions can be supported concurrently

- Feature code remains untouched

Rather than branching firmware per board, we treat board variants as configuration selections:

- Different HAL bindings

- Same device contracts

- Same product logic

This keeps the codebase cohesive and avoids long-term fragmentation.

Enabling Modular System Scaling

vBus products are designed to scale:

- New peripherals

- Optional modules

- Regional variants

- Product-line extensions

Firmware abstractions make this additive rather than invasive.

New modules plug into:

- Existing service contracts

- Existing scheduling logic

- Existing telemetry paths

The system grows by composition, not modification.

This is how iteration remains fast even as complexity increases.

Designing Abstractions That Age Well

Not all abstractions are equal. Poor abstractions slow iteration instead of enabling it.

We design abstractions with three principles:

1. Represent Physical Truth

Interfaces mirror real-world constraints:

- Power is not “on/off”; it has transitions

- Sensors have stabilization time

- Communication has latency

This prevents abstraction leakage later.

2. Avoid Over-Generalization

Interfaces are specific enough to be meaningful.

Generic abstractions become brittle when real behavior diverges.

3. Make Behavior Explicit

State, timing, and ownership are visible in interfaces.

Nothing relies on implicit assumptions.

This clarity is what enables confident change.

Iteration Without Regression Anxiety

One of the most underappreciated benefits of firmware abstraction is psychological.

Engineers move faster when:

- Changes feel contained

- Impact is predictable

- Verification is repeatable

Abstractions provide that confidence. Engineers can iterate aggressively, knowing that behavior outside their change boundary is unaffected.

This is how iteration stays fast without becoming reckless.

Firmware as a System Interface

In vBus products, firmware is not just code—it is the glue that binds hardware, mechanical design, and user experience.

Abstractions ensure that:

- Hardware decisions remain flexible

- Product behavior remains stable

- Verification remains continuous

This is why firmware abstraction is not a refactoring tactic—it is a system-level design decision.

Conclusion: Iteration as an Engineered Capability

Fast iteration is not achieved by writing code faster. It is achieved by engineering for change.

By treating firmware abstractions as first-class product infrastructure, we enable:

- Early and confident pre-verification

- Parallel hardware and firmware development

- Smooth board revisions

- Modular system growth

- Predictable integration cycles

The result is a development process where iteration is not disruptive—it is routine.

This is how Hoomanely products reach maturity quickly without sacrificing rigor. Firmware abstractions turn change from a risk into a controlled, repeatable operation—and that is what enables real velocity in embedded systems.