How We Reduced False Detections by Training on “Bad” Indoor Data

Introduction

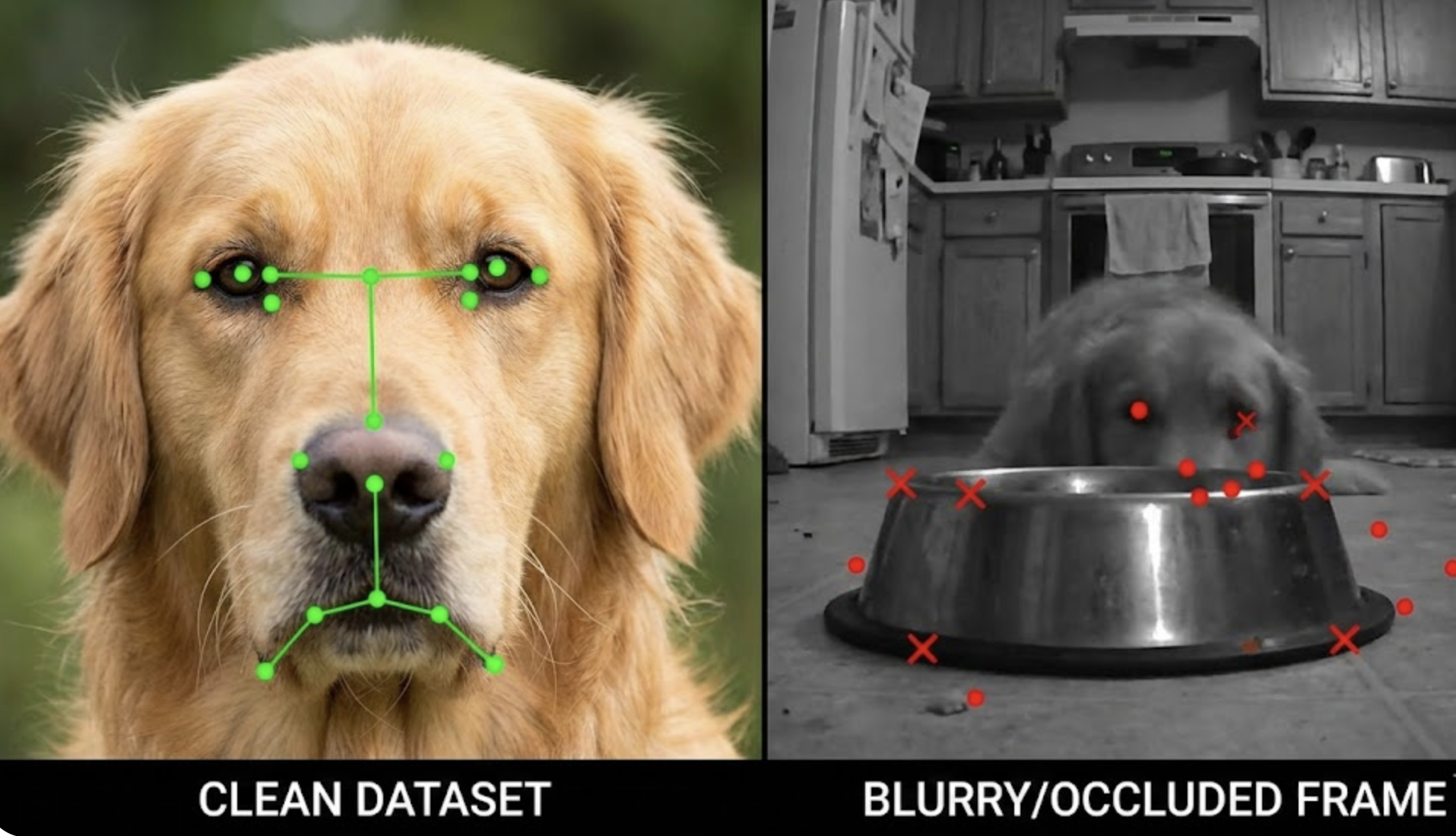

Landmark detection models often look impressive during offline evaluation - clean datasets, sharp images, balanced lighting, and tidy annotations. But the real world is rarely that polite. At Hoomanely, we deploy dog‑face landmark detection models (eyes, nose, facial keypoints) on always‑on indoor devices mounted on feeding bowls. These environments introduce motion blur, partial occlusions, odd camera angles, harsh indoor lighting, shadows, reflections, and plenty of frames that are simply bad.

Early versions of our models performed well on standard benchmarks but produced an unacceptable number of false detections indoors - eyes detected on fur, noses hallucinated on bowls, or landmarks snapping to background edges. This post describes how we reduced those false detections by deliberately training on bad indoor data: noisy, imperfect, and representative of reality.

We’ll walk through the problem, our approach, the training process, results, and key learnings - with enough detail for other engineers to replicate the strategy.

Problem: Clean Datasets, Dirty Reality

Most public dog‑face datasets are collected under controlled or semi‑controlled conditions:

- Frontal or near‑frontal faces

- Reasonable lighting

- Minimal occlusion

- High image quality

Our deployment environment looked very different:

- Low‑angle views from a bowl‑mounted camera

- Indoor lighting with yellow casts and harsh shadows

- Motion blur from excited dogs eating

- Partial faces (only one eye, nose partially visible)

- Non‑dog frames where the dog briefly leaves the scene

The result was a high false‑positive rate. The model confidently predicted landmarks even when the dog’s face was not clearly visible. Offline metrics looked fine, but real‑world performance was not.

Core issue: the model had never seen failure cases during training.

Approach: Treat Bad Data as a First‑Class Citizen

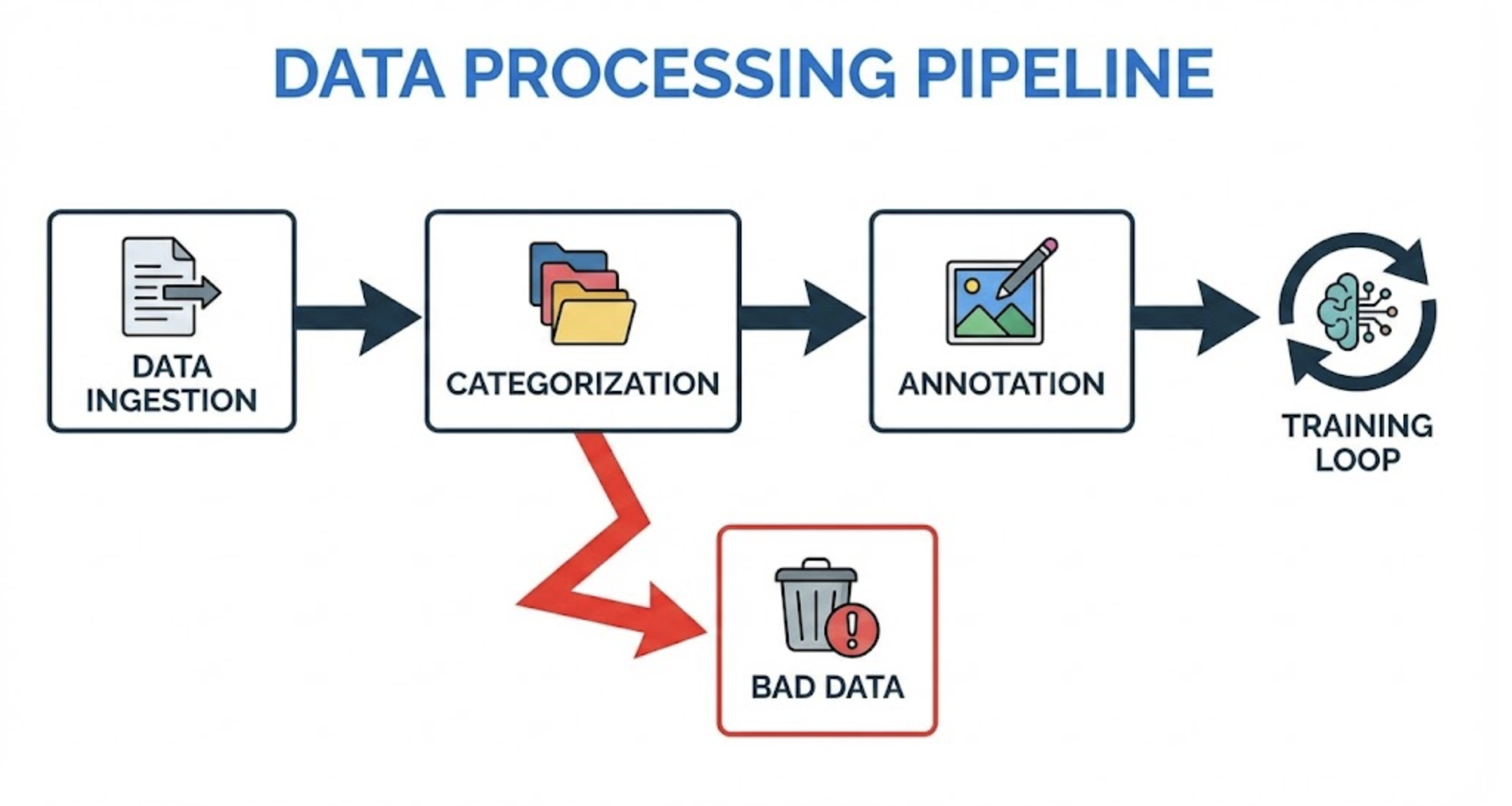

Instead of endlessly tweaking thresholds or post‑processing heuristics, we changed the training philosophy:

If the model fails in production, that failure must appear in training.

Our approach had three pillars:

- Actively collect bad indoor data from real devices

- Label negative and ambiguous frames, not just perfect faces

- Fine‑tune instead of retraining from scratch, preserving strong priors

This was less about increasing dataset size and more about increasing dataset truthfulness.

Process: How We Built the Indoor Failure Dataset

1. Data Collection from Production Devices

We sampled frames directly from deployed bowl cameras across different homes and conditions:

- Day vs night lighting

- Dogs of different sizes and fur patterns

- Eating, sniffing, walking away

Crucially, we did not filter aggressively. Frames that looked unusable to humans were intentionally kept.

2. Defining “Bad” Data Categories

We categorized indoor frames into explicit buckets:

- Partial face visible (one eye, nose cut off)

- Severe motion blur

- Face‑adjacent views (cheek, ear, or fur only)

- Non‑dog frames (bowl, floor, human hand)

- Occluded landmarks (eye covered by fur or motion)

This helped annotation and later analysis.

3. Annotation Strategy

Rather than forcing landmarks everywhere, we introduced stricter rules:

- Landmarks labeled only if clearly visible

- Ambiguous regions left unlabeled

- Explicit negative samples with no landmarks

This taught the model when not to predict.

4. Training Setup

- Base model: lightweight CNN‑based landmark detector optimized for edge

- Pretraining: public dog‑face datasets

- Fine‑tuning: mixed clean + indoor bad data

- Loss: weighted landmark loss with penalty for confident false positives

We intentionally over‑sampled indoor failure cases during fine‑tuning.

Results: Fewer False Positives, Better Stability

After introducing bad indoor data, we observed:

- Significant drop in false eye and nose detections

- Improved temporal stability across frames

- Slight reduction in recall - but a much larger gain in precision

In production metrics:

- False detections reduced by ~30–35% in indoor conditions

- Overall F1 score improved despite harder data

- Fewer downstream errors in thermal overlay and health inference

Most importantly, failure cases became predictable instead of chaotic.

Why Training on Bad Data Works

1. Models Learn Boundaries, Not Just Patterns

Clean datasets teach what is a dog face. Bad data teaches what is not.

2. Confidence Calibration Improves

Exposure to ambiguous frames reduces over‑confident predictions.

3. Downstream Systems Become More Reliable

Our landmark outputs feed into:

- Thermal eye temperature estimation

- Health trend analysis

- Anomaly detection

Reducing false positives upstream improves everything downstream.

Common Mistakes We Avoided

- Filtering bad data too early - it must survive until training

- Forcing labels everywhere - ambiguity is a valid signal

- Chasing recall blindly - precision mattered more for our use case

Key Takeaways

- Real‑world failures must appear in training data

- Bad data is often more valuable than more data

- Precision gains can outweigh small recall losses

- Fine‑tuning with failure cases stabilizes edge models

If your model looks great offline but struggles in production, the solution may not be a new architecture - it may simply be training on the data you’ve been avoiding.