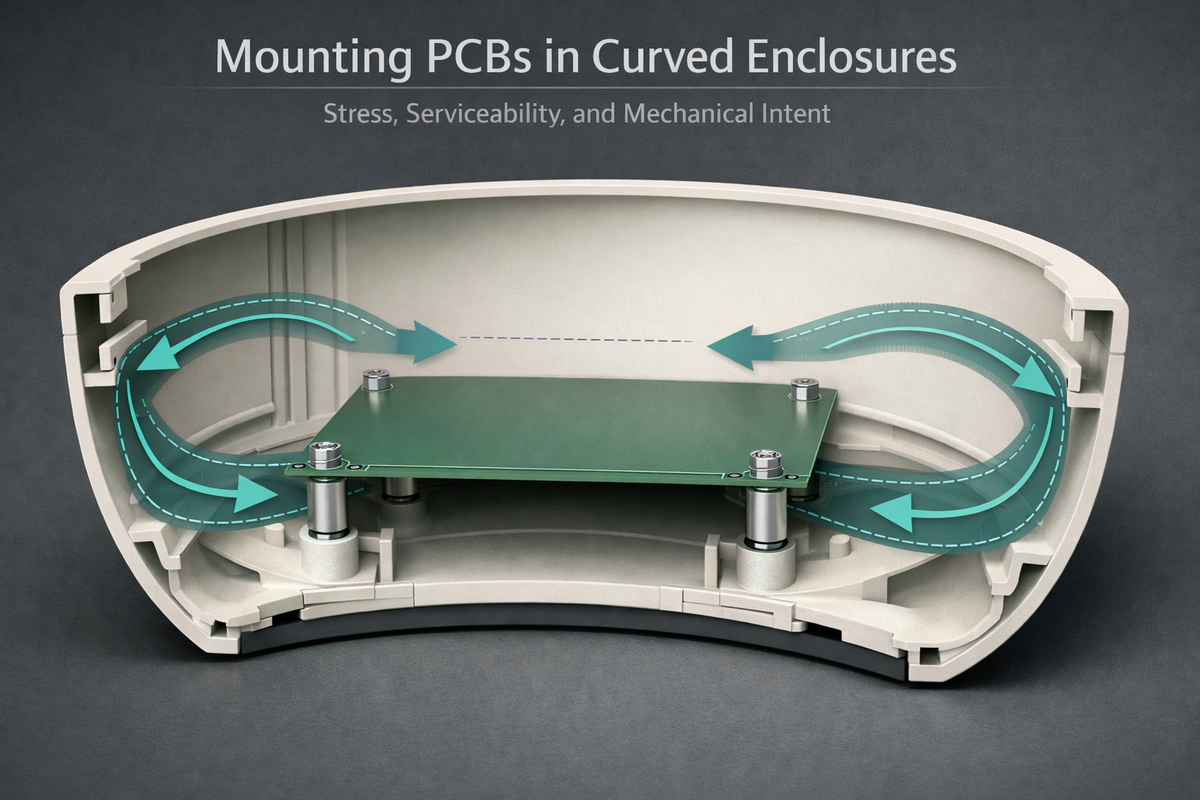

Mounting PCBs in Curved Enclosures: Engineering for Stress, Serviceability, and Longevity

Introduction: When Geometry Becomes a Mechanical Constraint

Flat PCBs prefer flat worlds.

Curved enclosures do not offer that luxury.

In products like our bowl, industrial design demands organic forms—continuous curves that feel natural in the hand, integrate seamlessly into living spaces, and support fluid interaction. But behind that curvature sits a rigid PCB populated with silicon, copper, and solder joints that are fundamentally intolerant of mechanical ambiguity.

Mounting electronics inside curved enclosures is not a packaging exercise. It is a structural engineering problem where stress paths, tolerances, and service access determine whether a product remains stable over years of use—or slowly accumulates invisible mechanical fatigue.

At Hoomanely, we approach curved-enclosure mounting as a co-design discipline: the PCB, enclosure, fasteners, and harnesses are engineered as a single mechanical system. The goal is not simply to “make it fit,” but to ensure that stress is controlled, strain is predictable, and serviceability is preserved without compromising industrial design.

This article outlines how we design PCBs and enclosures—especially in curved products like the bowl—to achieve long-term mechanical reliability and fast, confident serviceability.

Curvature Changes the Stress Model

Why Curved Enclosures Are Different

In flat enclosures, mounting forces distribute symmetrically.

In curved enclosures, forces resolve along arcs.

This changes everything:

- Screw preload vectors are no longer perpendicular to the PCB

- Enclosure flex introduces tangential stress

- Local curvature amplifies tolerance stack-up

- Thermal expansion follows non-linear paths

A PCB mounted into a curved shell is never purely “at rest.” It is always negotiating between its own planar rigidity and the enclosure’s geometric intent.

Recognising this early is essential. The mistake is to treat the PCB as the primary structure and the enclosure as a cosmetic shell. In curved products, the enclosure is the structure, and the PCB must be mounted in a way that respects that reality.

Design Principle #1: The PCB Must Never Be Forced to Conform

A rigid PCB should never be bent to fit curvature.

Instead, curvature is absorbed by:

- Stand-offs

- Floating constraints

- Controlled contact points

- Compliant interfaces

For bowl-class products, our PCB mounting strategy ensures that:

- The PCB remains mechanically planar

- All curvature is resolved in the enclosure geometry

- No mounting operation induces torsion or bowing

This starts with a simple rule: the PCB outline is optimized for clearance, not contact. The board never traces the enclosure wall. It lives inside it.

Mounting Architecture: Decoupling Shape from Structure

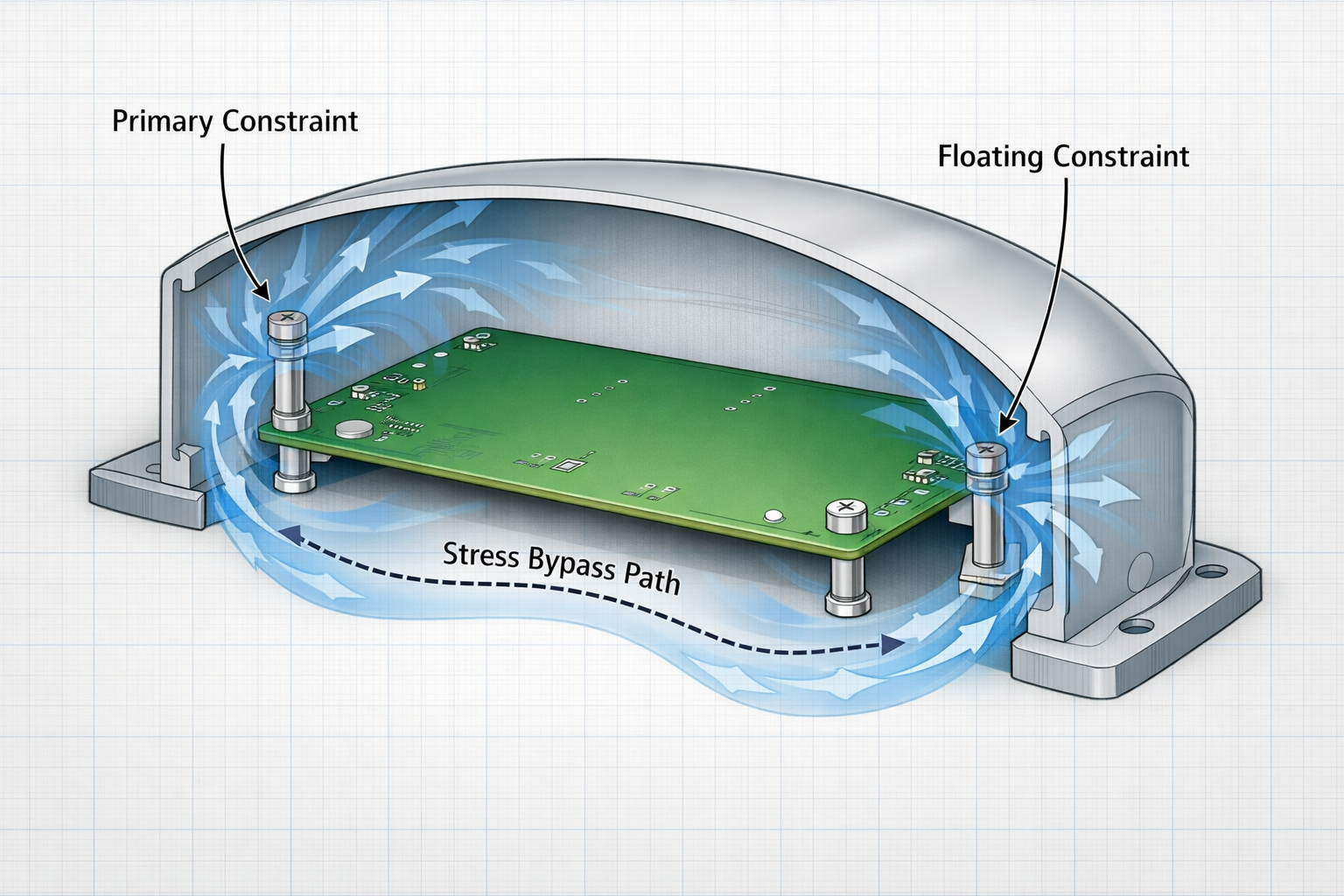

Three-Point Stability Over Full Constraint

In curved enclosures, over-constraining a PCB is the fastest way to inject stress.

Rather than fixing the board rigidly at every available point, we design mounting schemes that:

- Fully constrain position

- Partially constrain rotation

- Allow controlled micro-compliance

Most bowl assemblies use a three-point primary mounting strategy, where:

- Two points define the plane

- One point defines the reference

- Secondary features provide guidance, not force

This ensures:

- No stress from enclosure flex

- No tolerance-induced warp

- Stable alignment across temperature and time

Stand-Off Geometry as a Stress Tool

Stand-offs are not spacers—they are mechanical interfaces.

In curved products, stand-offs are:

- Height-tuned to maintain planar PCB alignment

- Positioned to avoid high-curvature zones

- Designed with fillets to reduce stress concentration

We avoid sharp transitions between stand-off and enclosure. Rounded bases distribute load, while controlled compression limits screw-induced strain.

Every stand-off location is chosen based on stress flow, not convenience.

Design Principle #2: Mounting Must Survive Human Interaction

Products like bowls are handled, moved, cleaned, and occasionally bumped. These actions introduce real-world loads that don’t appear in CAD.

We design mounting systems assuming:

- Repeated lifting and placement

- Surface vibrations

- Minor impacts

- Uneven support during handling

This translates into:

- No cantilevered PCB edges

- No mounting points near thin enclosure walls

- No reliance on friction alone

The PCB should feel mechanically “quiet” even when the enclosure experiences motion.

Thermal Expansion in Curved Volumes

Curved enclosures expand differently than flat ones.

As temperature changes:

- Plastic shells expand radially

- Metal inserts expand axially

- PCBs expand minimally and anisotropically

If these expansions are rigidly coupled, stress accumulates at:

- Screw joints

- Copper planes

- BGA solder balls

To prevent this, our designs incorporate:

- Slotted mounting holes in secondary locations

- Isolated metal inserts

- Defined slip planes between PCB and enclosure

Thermal motion is expected—and engineered for—not resisted.

Design Principle #3: Serviceability Is a Mechanical Requirement

A product that cannot be serviced without inducing stress is not serviceable.

In curved enclosures, access angles matter. A PCB that can be mounted easily may still be impossible to remove cleanly.

Designing for Straight-Line Extraction

Our serviceability requirement is simple:

A technician should be able to remove the PCB without bending it.

To enable this:

- PCBs are oriented for linear extraction paths

- Harnesses disconnect before PCB removal

- No mounting screw requires angled tools

- No clip requires enclosure flex to release

Curvature never blocks service motion.

Fasteners Chosen for Repeatability

Screw selection is part of stress design.

For curved enclosures:

- Thread-forming screws are avoided near PCBs

- Metal inserts are used where repeat service is expected

- Torque limits are defined and tested

Fasteners should clamp—not distort.

Harness Integration Without Load Transfer

In bowl-class products, harnesses often follow curved paths. If unmanaged, they become unintended structural members.

We explicitly prevent harnesses from:

- Pulling on PCB connectors

- Applying torque during enclosure closure

- Acting as springs during thermal cycling

This is achieved through:

- Harness strain relief before PCB termination

- Defined service loops

- Connector orientation aligned with natural cable exit paths

The PCB should never “feel” the harness.

Vibration and Long-Term Fatigue

Curved enclosures tend to amplify certain vibration modes. This can quietly fatigue solder joints or mounting interfaces over time.

To counter this:

- PCB mass is centrally supported

- High-mass components are aligned with mounting points

- Enclosure ribs are placed to damp, not reflect, vibration

Mechanical energy should flow around the PCB, not through it.

Material Pairing: PCB and Enclosure as a System

Material choice is not independent.

For curved enclosures, we evaluate:

- CTE mismatch between PCB and shell

- Local stiffness gradients

- Insert materials and their expansion behaviour

In bowls, where plastics dominate, we design PCBs assuming:

- The enclosure will move more than the board

- Contact points must accommodate that motion

- Rigid coupling is the enemy of longevity

This mindset prevents stress from ever accumulating in solder or copper.

Validation Beyond Fit

A PCB that fits is not necessarily safe.

Our validation focuses on:

- Stress under assembly torque

- Stress during enclosure flex

- Stress during removal and reinstallation

- Stress after thermal soak

The success metric is not the absence of cracks—it is the absence of preload memory. After removal, the PCB should return to a neutral state.

Design Outcomes in Bowl-Class Products

This co-design approach delivers tangible results:

- PCBs remain flat throughout product life

- No latent stress in solder joints

- Consistent assembly torque feel

- Fast, predictable service operations

- Enclosures maintain industrial design integrity

Most importantly, mechanical reliability is no longer dependent on perfect assembly—it is inherent in the design.

Conclusion: Curvature Demands Mechanical Intent

Mounting PCBs in curved enclosures is not about clever tricks or compensating for industrial design. It is about accepting curvature as a first-class mechanical constraint and designing electronics that coexist with it gracefully.

At Hoomanely, we do not ask PCBs to tolerate stress—we engineer systems where stress never accumulates. Through controlled constraints, compliant interfaces, and service-first thinking, our curved products like the bowl achieve both elegance and durability.

This is not a compromise.

It is precision applied where geometry and mechanics intersect.

When enclosure curvature, PCB rigidity, and human interaction are treated as a single system, the result is hardware that not only works—but stays trustworthy, serviceable, and stable over time.