Rethinking Hardware Prototyping: How We Build Faster Without Cutting Corners

There's a peculiar rhythm to hardware development that anyone in the field knows well. You design a circuit, order boards, and then... you wait. Weeks pass. The boards arrive. You test them, discover issues, make fixes, and the cycle begins again. Each iteration feels like watching paint dry, except the paint costs thousands of dollars and your launch timeline keeps slipping.

For startups like Hoomanely, this traditional approach isn't just slow—it's existential. We don't have the luxury of six-month development cycles or the safety net of an endless runway. But we also refuse to compromise on quality or skip the fundamentals of good engineering.

So we asked ourselves: what if hardware development didn't have to be a waiting game?

The Traditional Trap

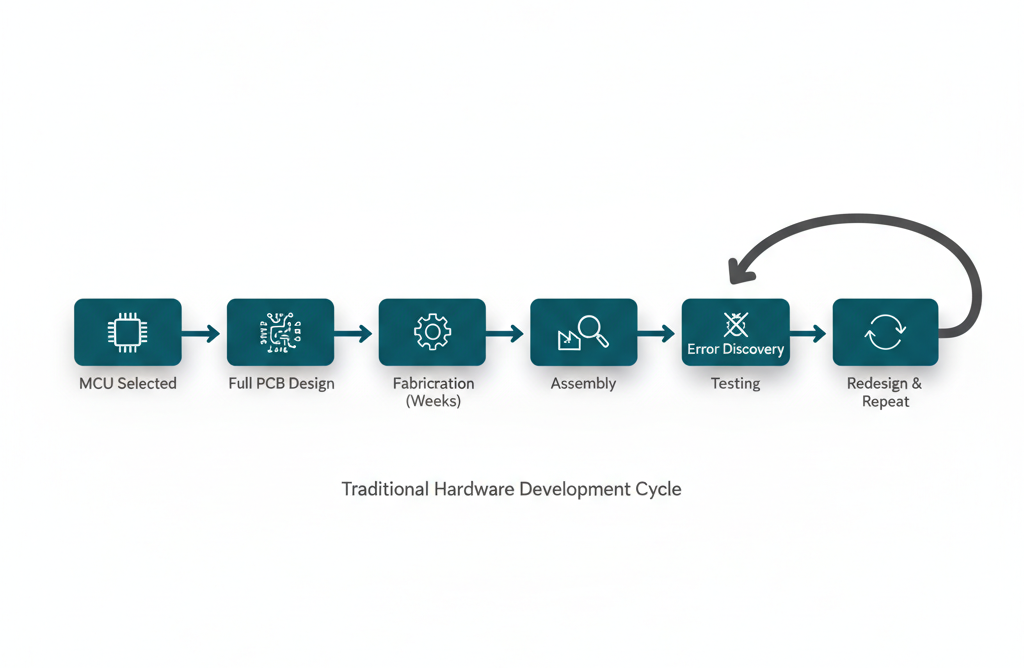

The conventional hardware development process is deeply sequential. You pick a microcontroller, design your entire system around it, order PCBs, wait for manufacturing, assemble them, and finally—finally—start testing. If that MCU doesn't work out? If the documentation was incomplete or the SDK has bugs? You're back to square one.

This linear approach made sense in an era when PCB manufacturing took months and component choices were limited. But in 2025, with rapid prototyping services and an explosion of new silicon hitting the market, this old methodology has become the bottleneck.

For a startup, every week spent waiting is a week not spent learning. And in hardware, learning only happens when you have physical boards in hand.

Our Philosophy: Parallel Progress Over Sequential Waiting

At Hoomanely, we still follow the same fundamental engineering roadmap that everyone does: proof of concept → prototype → validation → production. We haven't invented a magical shortcut that skips testing or validation. Instead, we've rearchitected how those steps happen.

Our core insight was simple: why should one decision block all the others?

This philosophy manifests in three practical approaches that have transformed how we work.

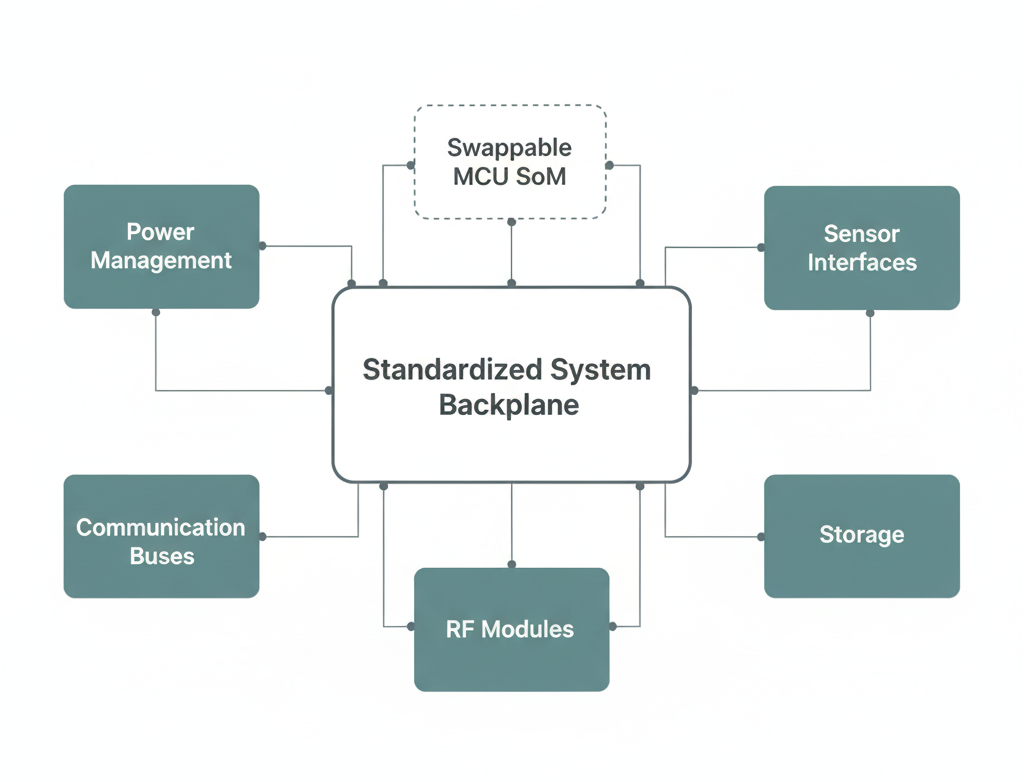

1. Building a Hardware "Platform" Instead of Projects

Every time you start a new hardware project with a different microcontroller, you typically rebuild everything from scratch. New schematics, new pin mappings, new power trees, new bring-up procedures. It's exhausting and error-prone.

We created what we call Virtual Interface PCB (VIP) Architecture to solve this. Think of it as designing the "motherboard" once and treating the microcontroller as a swappable module.

Here's how it works: we designed a standardized system architecture with consistent pinouts for all the key subsystems—power management, sensors, radios, storage, and communication buses. These connect through standardized headers and follow the same routing rules across projects.

When we need to work with a different MCU family, only the System-on-Module (SoM) section changes. Everything else—the power supply design, sensor interfaces, peripheral connections—stays identical.

Why this matters for a startup: Instead of spending three weeks redesigning an entire board for a new processor, we spend three days adapting the interface layer. We can explore different silicon options without throwing away all our previous work. And crucially, every iteration benefits from our accumulated learnings about signal integrity, grounding strategy, and thermal management.

It's like how software developers use APIs and abstraction layers. We brought that same modularity thinking to hardware.

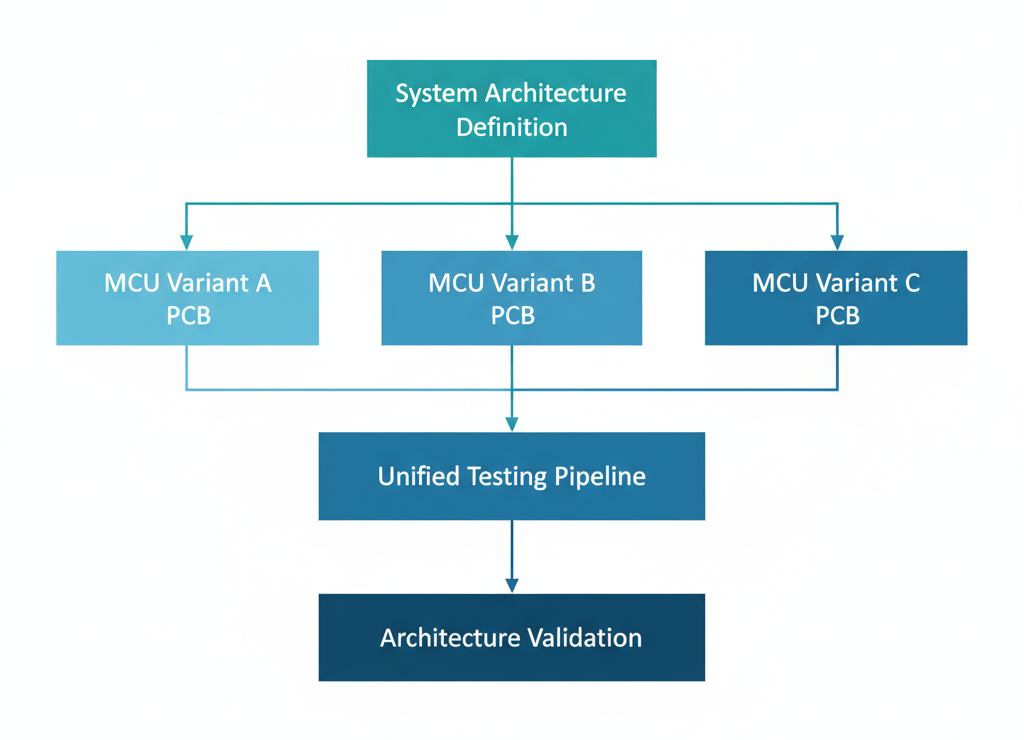

2. Testing Multiple Futures Simultaneously

Here's a scenario that's haunted many hardware teams: you commit to a new, cutting-edge microcontroller. The specs look perfect. You design your entire product around it. Then you discover the SDK is buggy, the documentation has gaps, and vendor support is... minimal. Your project is now stuck.

Our solution? We don't commit to just one future. We explore several in parallel.

For each new design, we create multiple PCB variants using different MCU families—perhaps one with STM32, another with ESP32, and a third with nRF52. The critical detail: only the MCU and its immediate support circuitry differ. All sensors, radios, power supplies, and connectors remain identical across variants.

This approach gives our firmware team real hardware to work with immediately, even if one MCU hits a roadblock. Our testing team can compare power consumption, noise characteristics, and communication reliability across platforms under truly identical conditions. And our hardware engineers aren't blocked waiting for one specific chip to work.

The startup advantage: Risk becomes redundancy. When you're moving fast, encountering unknowns is inevitable. Traditional teams get blocked by these unknowns. We work around them. By the time we determine which MCU is optimal, we've already validated the entire system architecture. No time lost to sequential decision-making.

3. Manufacturing as a Sprint, Not a Marathon

Even the best architecture doesn't help if manufacturing takes forever. This is where choosing the right partners becomes critical.

We work extensively with JLCPCB because they've optimized for exactly what startups need: speed, flexibility, and low barriers to entry.

The practical benefits are significant:

- Low minimum quantities: We can order just five boards per revision. Perfect for R&D without burning capital on inventory we might not need.

- Integrated component sourcing: Components are ordered, stored long-term in their system, and reused across batches. No more scrambling to reorder parts for each revision.

- End-to-end assembly: We upload design files (Gerber, BOM, and pick-and-place) and receive fully assembled boards. No coordinating between three different vendors.

- Transparent tracking: Real-time visibility into fabrication, assembly, and shipping stages. We know exactly when boards will arrive and can plan accordingly.

The speed difference is dramatic:

| Phase | Traditional Flow | Our Flow with JLCPCB |

|---|---|---|

| Design to order | 3–5 days + manual quoting | Instant quote + DFM check |

| Manufacturing | 3–4 weeks | 5–10 days (assembled) |

| Testing cycle | After all boards arrive | Parallel across MCU variants |

| Total iteration time | ~8–12 weeks | ~3 weeks end-to-end |

By the time traditional development teams receive their first prototypes, we're testing our second revision. That velocity compounds over months.

Why This Matters for Startups

Speed isn't just about ego or bragging rights. For a startup, velocity is survival.

The faster we iterate, the faster we learn what works and what doesn't. The faster we learn, the faster we reach product-market fit. And reaching product-market fit before running out of runway is literally the only game that matters.

But here's what we don't do: we don't skip validation. We don't test on breadboards and hope it works in production. We don't cut corners on EMI testing or thermal analysis.

Our approach gets us to real-world testing early—on production-grade PCBs with accurate thermal behavior, genuine EMI performance, and reliable mechanical fit—long before mass production. We're not moving fast by skipping steps. We're moving fast by doing multiple steps simultaneously.

The Bigger Picture

Traditional hardware design moves like a train on a single track: one MCU, one prototype, one revision at a time. Each station must be completed before the train moves forward.

At Hoomanely, we move like water finding multiple paths down a mountain. We test architectures, evaluate MCUs, and refine manufacturing processes simultaneously. Some paths hit obstacles. Others flow freely. But we're always moving.

Virtual Interface PCB architecture, parallel MCU development, and rapid prototyping services aren't revolutionary concepts individually. Plenty of teams use modular design. Many companies order from JLCPCB. The innovation is in combining these approaches into a coherent philosophy: minimize dependencies, maximize parallel progress, and keep the team learning continuously.

This is just one of many methods we use to design, test, and refine hardware faster. But it represents something fundamental about how we think: the best way to reduce risk isn't to plan more carefully—it's to test more frequently.