Retrieval Cost Engineering for OpenSearch RAG

A production RAG system feels “fast” when it’s consistent: answers arrive quickly, follow-ups don’t suddenly slow down, and costs don’t jump with traffic. The biggest lever to achieve that isn’t usually the model—it’s retrieval. When retrieval is engineered like a disciplined subsystem (with budgets, plans, batching, and caching), you get predictable latency, stable relevance, and cost that scales with users—not with accidental query fanout.

This post is a practical deep dive into retrieval cost engineering for OpenSearch-backed RAG: how to detect and reduce fanout, how to plan and batch queries so you don’t pay round-trip penalties repeatedly, and how to cache safely (IDs, chunks, and hydrated context) without breaking freshness or trust. The goal is simple: keep retrieval measurable, budgeted, and stable—so your assistant stays responsive as you scale.

Why retrieval cost engineering matters

In most OpenSearch RAG stacks, retrieval “looks” cheap because each query is fast on its own. The real cost emerges from the pattern:

- One user turn becomes multiple intents (“compare”, “recommend”, “explain why”)

- Each intent triggers hybrid retrieval (filters + BM25 + vector)

- Rerankers pull additional candidates or run a second pass

- Follow-ups repeat the same constraints and re-fetch similar chunks

The result is silent fanout: OpenSearch QPS and tail latency scale with how your pipeline behaves, not with user demand. That creates three common production failures:

- Cost drift: OpenSearch compute scales up “mysteriously” even when DAU is flat.

- Tail latency instability: P95/P99 spikes because a subset of turns triggers big fanout and rerank loops.

- Relevance volatility: aggressive retries and second-pass queries can change top-K sets and make answers feel inconsistent.

Retrieval cost engineering is about making those behaviors explicit, bounded, and testable—so you can reduce load without gambling on relevance.

Make fanout visible: measure queries per turn like an SLO

Before you optimize, you need an “x-ray” metric that shows what one user message triggers.

Core metric: Queries Per Turn (QPT)

- Count every OpenSearch request triggered by one user message, including reranks and retries.

Also track shape, not just averages:

- QPT P50 / P95 / P99 (P99 tells you where budgets break)

- Rerank passes per turn (and how many extra queries they trigger)

- Unique query templates per turn (signals planner complexity)

- Retrieval share of latency (time spent in retrieval vs generation)

- Bytes returned per turn (hidden “hydration” cost proxy)

A surprisingly effective early win is to define a simple budget target:

- Example: QPT P95 ≤ 6 for most endpoints

- Example: Rerank passes ≤ 1 unless explicitly required

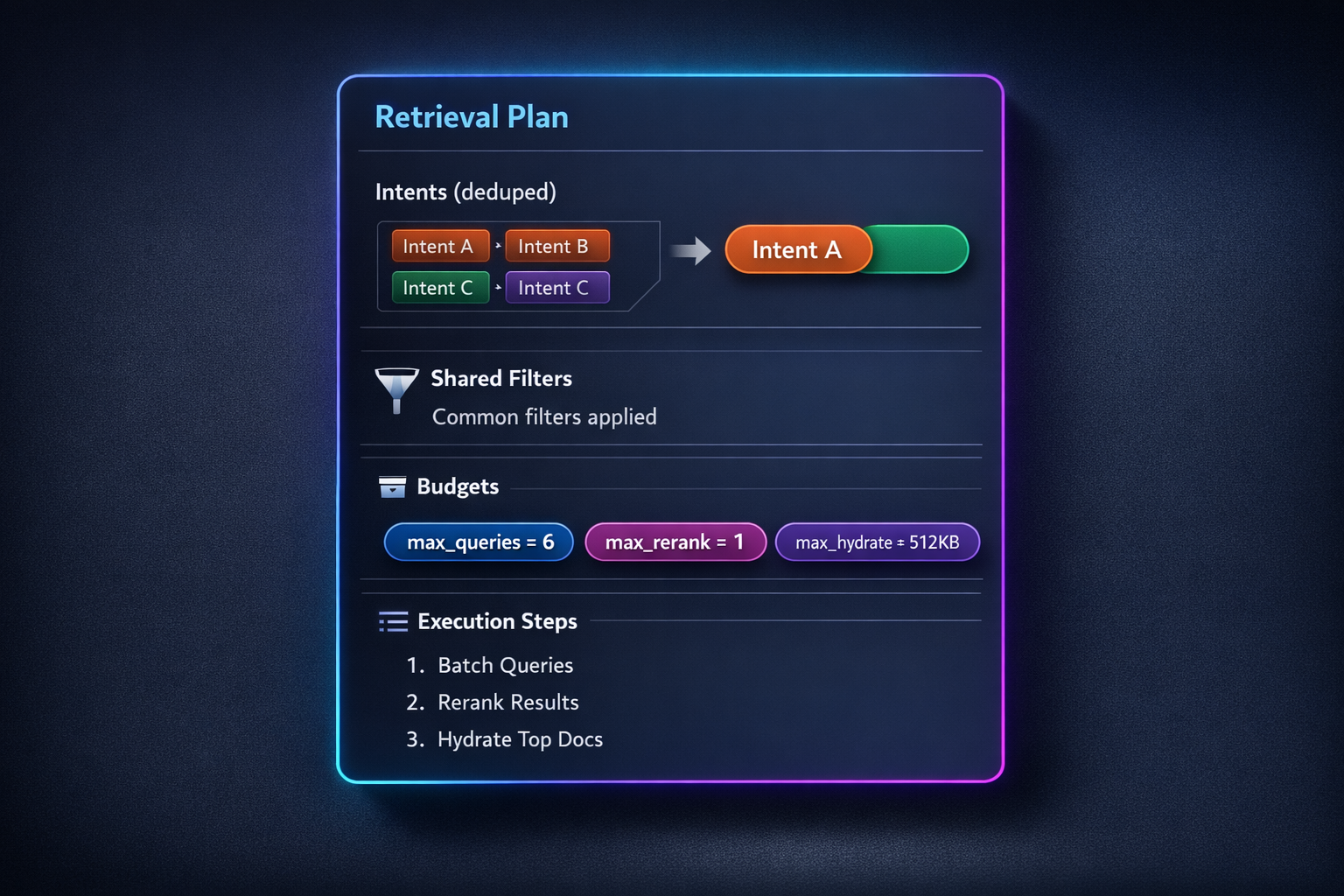

Query planning: treat retrieval like a compiled plan

Most RAG pipelines “retrieve as they think”: a step needs context, so it queries; reranker needs more, so it queries again. That’s easy to build—and expensive to run.

Query planning flips the control flow:

- Extract the turn’s information needs

- Deduplicate overlaps

- Compose shared filters

- Allocate a budget

- Execute as a plan (batched and bounded)

Think of it as compiling a retrieval program.

1) Deduplicate overlapping intents

A single user message frequently contains multiple phrasings of the same need:

- “Compare A and B”

- “What are the trade-offs?”

- “Which is better for X?”

If you retrieve separately for each, you pay multiple times for similar documents and chunks.

Practical approach (works without being fragile):

- Normalize intents into a small set of canonical asks:

- definition / explanation, comparison, procedural steps, trade-offs, recommendation

- Extract entities and constraints (A, B, X, time window, scope)

- Merge intents when:

- entities overlap strongly and

- the required evidence sources are similar and

- the output can share context

Output of this step isn’t “3 questions.” It’s “2 retrieval intents that cover the turn.”

2) Prioritize intents by value under a budget

Not all intents deserve equal retrieval spend. A stable ordering that holds in production:

- Hard correctness needs (policy, safety, contract, exact references)

- User-/tenant-scoped evidence (most relevant to the user)

- Core domain docs (KB, specs, guides)

- Background/explanations (lowest retrieval priority)

Then enforce a turn budget:

- Max intents per turn (e.g., 2–3)

- Max total OpenSearch calls (e.g., 4–8)

- Max candidates for rerank (e.g., 50–120)

- Max hydrate bytes (e.g., 256KB–1MB)

If you hit the budget, don’t “try harder.” Degrade safely:

- Answer with what you have,

- Be explicit about what’s missing,

- Offer a next step (“If you want, I can zoom into X”).

3) Compose shared filters once per turn

Filters are often the most “wasteful repetition” source: every sub-query rebuilds the same filter set.

Common shared filters:

- tenant/org/user scope

- doc types

- time windows (“last 30 days”)

- product line / environment

- language, region

Planner rule: build a turn-level filter signature once, reuse it everywhere unless an intent overrides it.

This stabilizes both cost and relevance, and prevents accidental unfiltered queries.

Batched retrieval: reduce round trips, control tail latency

Once you plan, execution becomes simpler: fewer calls, fewer retries, fewer “accidental loops.”

Pattern A: Multi-search batching across intents

If multiple intents hit the same index and share filters, batch them into one request (or one internal batch call). Even when OpenSearch processes them individually, you reduce:

- connection overhead

- TLS handshake churn

- client-side queuing

- tail latency from sequential calls

When batching helps most:

- 2–4 intents per turn

- hybrid retrieval where each intent would otherwise run 2–3 queries

- high concurrency environments (batching reduces client bottlenecks)

Pattern B: Two-phase retrieval (IDs first, hydrate later)

A classic cost trap is hydrating too much too early.

Two-phase retrieval splits the work:

- Phase 1: fetch top doc IDs (or chunk IDs) with minimal payload

- Phase 2: hydrate only the winning subset into text snippets / chunks

Why it works:

- Most candidates never make it to the final context window

- Hydration dominates bytes returned

- You can cap hydration independently of ranking

Good defaults that stay stable:

- Phase 1: top 50–200 IDs (cheap)

- Phase 2: hydrate 10–30 chunks max, or cap by bytes

Pattern C: Candidate pooling for rerank (one rerank, not many)

Without pooling, you may rerank per intent:

- Intent A retrieves → reranks

- Intent B retrieves → reranks

- Intent C retrieves → reranks

Pooling flips it:

- Retrieve candidates for all intents

- Deduplicate by doc ID / chunk hash

- Rerank once on the pooled set

- Allocate final context slots by intent priority

This is one of the highest ROI fanout reducers because rerank loops are often the multiplier.

Pattern D: Deduplicate overlapping chunks at the boundary

Even with deduped intents, overlapping results happen:

- same doc appears in BM25 and vector

- same chunk appears via multiple queries

Always dedupe at:

- doc boundary (doc_id)

- chunk boundary (chunk_id or content hash)

- semantic boundary (near-duplicate detection if you have embeddings handy)

This reduces context bloat and improves answer stability.

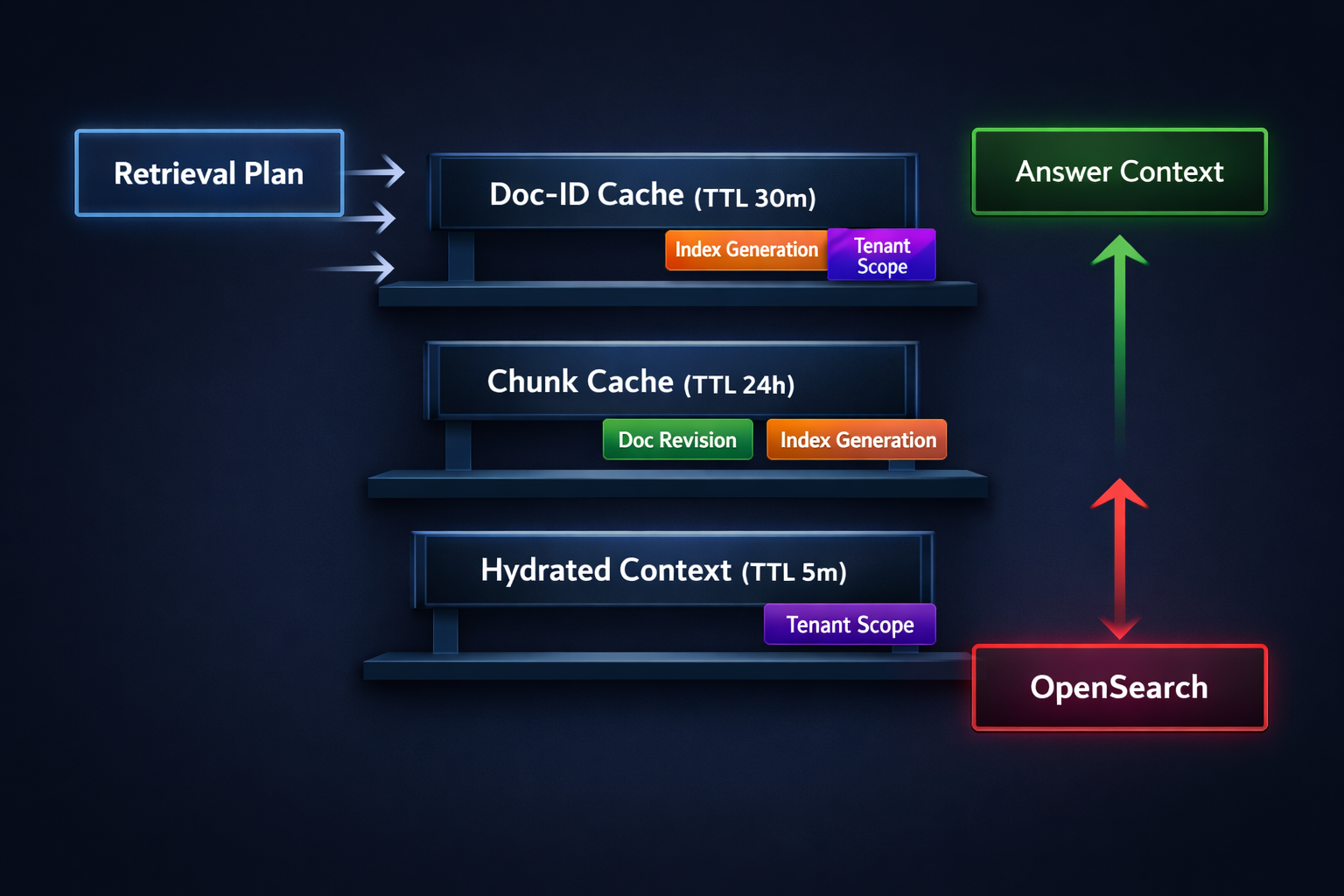

Caching that actually works: three layers, clear keys, predictable TTLs

Caching is where retrieval cost engineering becomes “set-and-forget”—but only if keys and invalidation are disciplined.

Layer 1: Doc-ID cache (high hit rate, low risk)

Stores: query_key → [doc_ids + scores + metadata]

Why it’s safe:

- IDs are small

- You can always rehydrate fresh text later

- Staleness risk is limited (the set might change, but it’s usually good enough within TTL)

Strong cache key includes:

- canonical query representation (normalized text or intent signature)

- filter signature (tenant scope, doc types, time range)

- index/version stamp

- retrieval mode (BM25/vector/hybrid) and embedding model id (if relevant)

TTL guidance:

- Stable KB: 6–24 hours

- Frequently updated corpora: 5–30 minutes

- Mixed: separate namespaces by source type

Layer 2: Chunk cache (big latency win in multi-turn)

Stores: doc_id + chunk_id (+ doc_revision) → chunk text + offsets + small metadata

This avoids repeatedly fetching the same chunk across:

- reranks

- follow-ups

- repeated intents

Key requirement: include a doc revision or last_updated stamp so updates automatically bypass old entries.

TTL guidance: hours to days (depends on update frequency)

Layer 3: Hydrated-context cache (highest payoff, highest staleness risk)

Stores: turn_signature → assembled final context blob

Use this when the “assembly” itself is expensive:

- multi-source context joining

- post-processing, cleaning, merging duplicates

- snippet formatting and provenance tagging

Keep it short-lived. This is a “tail-latency smoother,” not your primary cache.

TTL guidance: 1–10 minutes unless you have strong invalidation.

Freshness and invalidation: keep performance without losing trust

Freshness is the reason teams avoid caching. The trick is to treat freshness as a policy, not an accident.

Separate “freshness” from “correctness”

- It can be correct but not latest.

- Many user questions don’t require the newest doc revision; they require stable guidance.

So you categorize data:

- Stable corpus (docs, guides, evergreen KB)

- Evolving corpus (release notes, operational runbooks)

- Time-sensitive corpus (alerts, incident notes, daily metrics)

Different TTLs and bypass rules per category.

Simple invalidation mechanisms that scale

- Index generation stamp

- When you ingest updates, bump a generation number.

- Include it in cache keys (especially hydrated context).

- You “invalidate by moving forward.”

- Doc revision keys

- Chunk cache keys include

doc_revision. - Updated docs naturally become cache misses.

- Chunk cache keys include

- Scope-based namespaces

- Tenant/user scoped caches prevent cross-tenant leakage.

- You can flush a scope without global churn.

A practical approach to “fresh enough”

- If the question includes time signals (“latest”, “today”, “new release”), you:

- shorten TTL

- bypass hydrated-context cache

- rehydrate even if IDs are cached

- If it’s evergreen (“how to”, “explain”), you:

- lean on cache

- prioritize stability and latency

This is how you avoid a system that’s either always stale or always expensive.

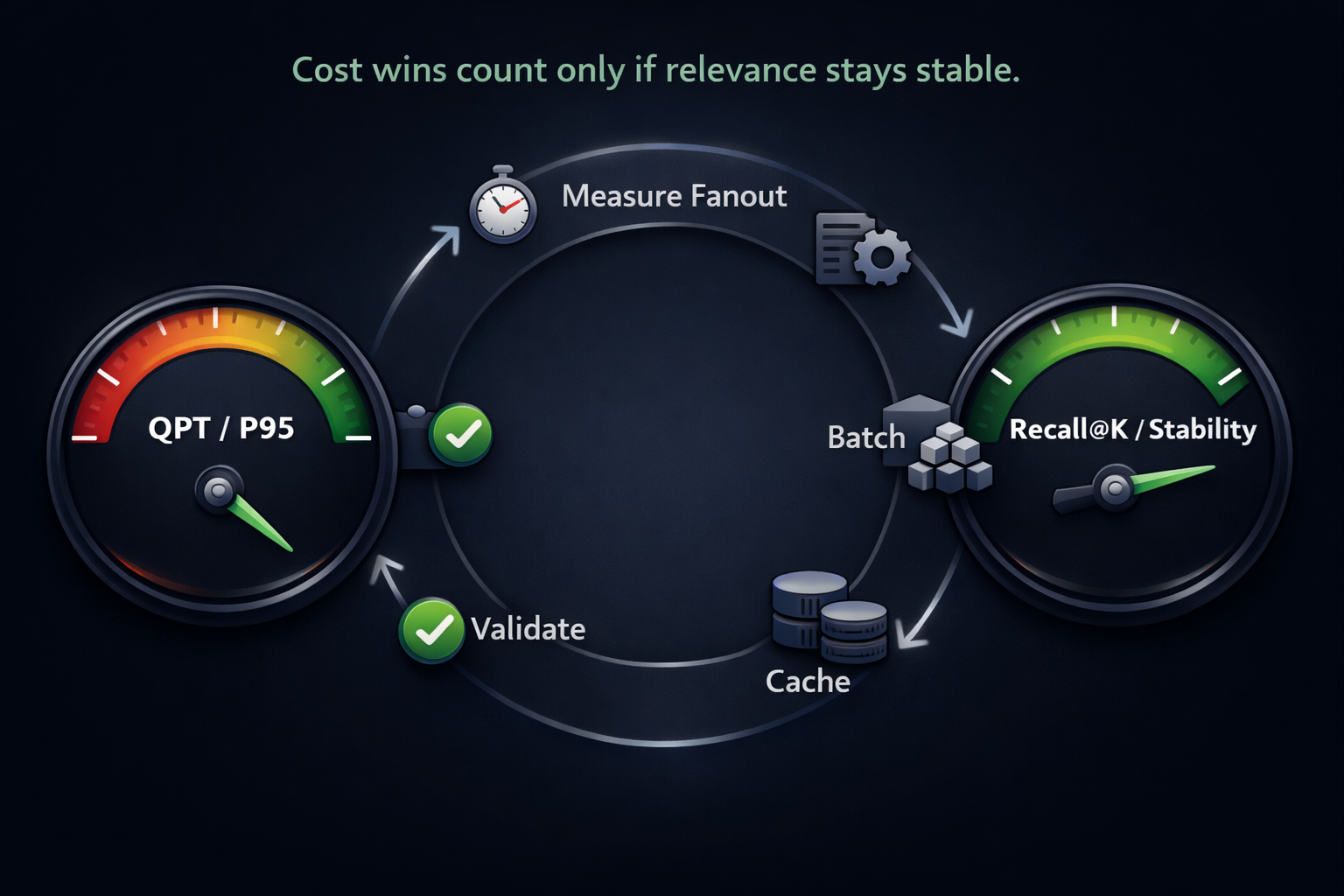

Validating that cost reduction didn’t hurt relevance

Retrieval cost metrics (hard numbers)

- QPT P50/P95/P99

- OpenSearch P95 latency

- Bytes returned per turn

- Rerank loop rate

Cache health metrics

- Hit rate per layer (ID / chunk / context)

- Evictions per minute (detect undersized cache)

- “Served after soft TTL” rate (staleness exposure)

Relevance proxies (practical)

- Recall@K on a small golden set (even 50–200 queries helps)

- Answer stability: same question → same citations/top docs across runs

- Follow-up amplification: do users ask more clarifying questions right after?

If relevance drops, don’t revert everything—tighten one lever:

- increase candidate pool slightly

- loosen dedupe threshold

- shorten hydrated-context TTL

- bypass caching for “time-sensitive” intents

In multi-turn assistants that combine knowledge base guidance with user- and device-derived summaries, the same constraints repeat across turns (time window, pet scope, device summaries). That’s where query planning and caching deliver strong wins: shared filters prevent accidental drift, chunk caching avoids rehydrating the same evidence repeatedly, and batched retrieval keeps tail latency stable during “follow-up heavy” conversations.

This pattern helps ensure that experiences built around products like EverSense and EverBowl remain responsive as usage scales—without needing to over-provision OpenSearch for worst-case fanout.

Key takeaways

- Treat retrieval as a budgeted subsystem: plan, batch, cap, and measure.

- Query planning (dedupe + shared filters + budgets) removes most accidental fanout.

- Batched retrieval reduces round trips and smooths P95/P99 under load.

- Three-layer caching works when keys include scope + versions, and TTLs match freshness needs.

- Validate with both cost metrics and relevance proxies—stability is part of quality.