Roadmap to Linux Device Drivers

Introduction

Linux powers everything from routers and EV chargers to drones, cameras, industrial machines, and the modern edge-AI stack. But behind every peripheral that "just works" lies a device driver — the thin layer of software that lets hardware talk to the Linux kernel.

For new embedded engineers, Linux device drivers often feel intimidating: kernel space, memory barriers, concurrency, interrupts… where do you even start?

This roadmap breaks the entire journey into clear, logical steps you can follow — from learning the basics of kernel space to writing your first character driver, adding interrupt handling, integrating with device trees, and finally building production-grade drivers that power real hardware.

Whether you're building embedded products, experimenting with Raspberry Pi, or working on advanced platforms, this guide gives you the exact path to become confident with Linux device drivers.

1. Understand the Foundations

Before writing any driver, you need a firm understanding of how the Linux kernel interacts with hardware.

Key Concepts to Master:

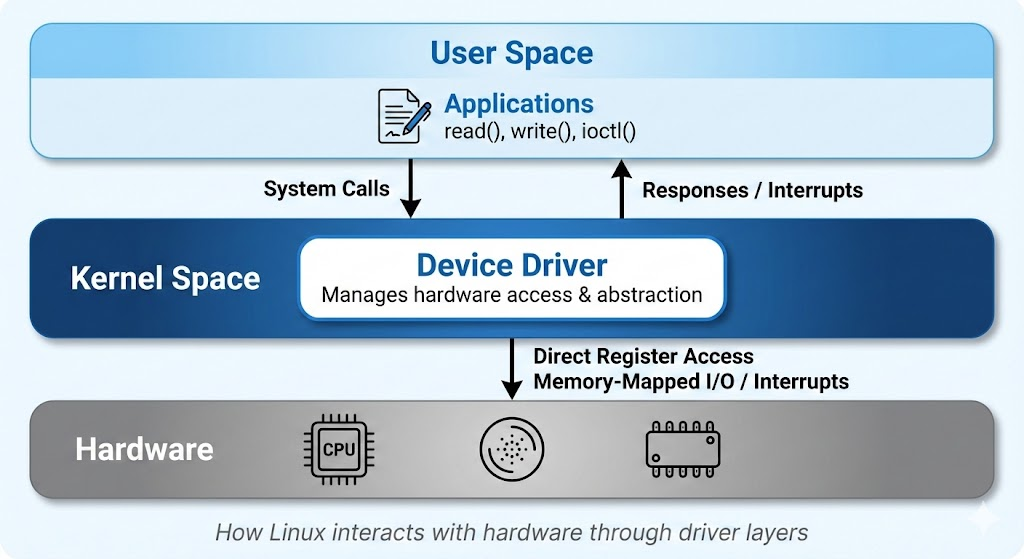

Kernel vs User Space — Drivers live in kernel space where they have direct hardware access, while applications run in user space with restricted privileges. This separation is fundamental to Linux's stability and security model.

System Calls Bridge the Gap — When applications call read(), write(), or ioctl(), these requests flow through system calls to your driver's implementation. Understanding this flow is crucial for designing effective driver APIs.

Kernel Modules (LKMs) — Drivers can be dynamically loaded at runtime using insmod and removed using rmmod, without requiring a full system reboot. This flexibility accelerates development cycles dramatically.

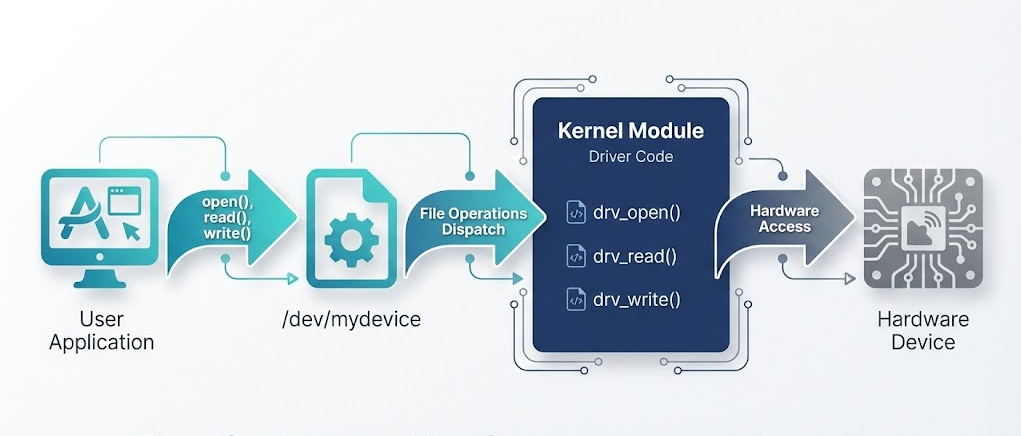

Device Files in /dev — Drivers expose their APIs through special files like /dev/i2c-1 or /dev/my_driver, making hardware accessible through familiar file operations.

Why It Matters: Understanding these layers helps you debug issues faster, structure your driver logically, and choose the right driver model for your hardware.

2. Start With Loadable Kernel Modules

The easiest entry point into driver development is learning how to build and load a kernel module.

Your First Goal: Create a simple kernel module that logs messages when loaded and unloaded.

Start by installing kernel headers for your system. Write a basic .c file implementing module_init() and module_exit() functions. Build it using a Makefile that references KDIR=/lib/modules/$(uname -r)/build. Load your module with insmod, then verify it's working with dmesg.

The output? Your first "Hello from kernel space" message — a rite of passage for every kernel developer.

This foundational step teaches you the module lifecycle, how to write Makefiles for kernel code, and how to use kernel logging effectively. These skills become second nature as you progress to more complex drivers.

3. Write a Character Device Driver

Most beginners start with character drivers, which are used for custom sensors, motors, GPIO expanders, and similar peripherals.

What You'll Learn:

Character drivers teach you how to allocate device numbers using alloc_chrdev_region, create /dev/<device> entries that applications can open, and implement the core file operations: open(), read(), write(), and release().

You'll work with kernel buffers, understand the difference between copy_to_user() and copy_from_user(), and tackle your first concurrency challenges. Should you use spinlocks or mutexes? The answer depends on your specific use case.

Why This Step Is Critical:

Character drivers form the foundation for UART drivers, SPI/I2C custom drivers, virtual drivers, and sensors or actuators in robotics. Once you finish this stage, you can control real hardware through simple file operations.

4. Master Interrupt Handling

The Problem: Polling hardware wastes CPU cycles and increases latency. Your system spends precious time constantly checking if something has happened.

The Solution: Use interrupts (IRQs) to react instantly to hardware events.

You'll learn to register interrupt handlers with request_irq(), understand the critical distinction between top-half and bottom-half processing, and use workqueues, tasklets, or threaded IRQs appropriately. Debouncing interrupts and handling concurrency safely become essential skills.

The process is straightforward: configure the interrupt line (GPIO or native IRQ), register it in your driver, implement a handler that stays short and fast, then offload heavy work to bottom-half processing if needed.

Mastery of IRQs is essential for advanced drivers powering sensors, CAN controllers, touchscreens, and network devices. Without this knowledge, you'll struggle with any real-time or event-driven hardware.

5. Learn the Device Tree for ARM Boards

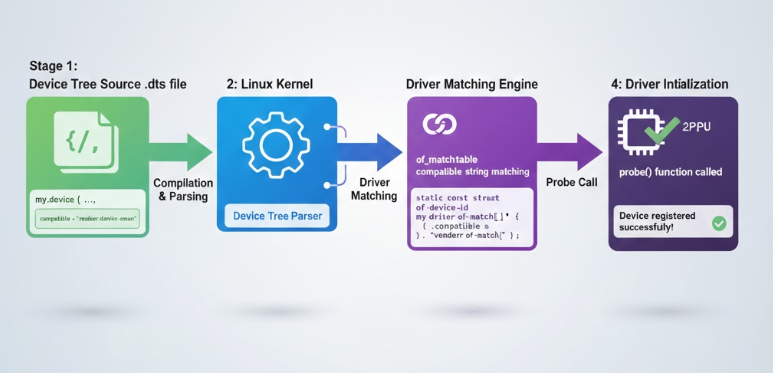

Embedded Linux relies heavily on the device tree to describe hardware configuration without hardcoding it into the kernel.

What You'll Master:

You'll learn to write .dts overlays, bind drivers through compatible strings, add custom hardware blocks, and expose GPIOs, I2C/SPI buses, and interrupts. The of_match_table becomes your bridge between hardware description and driver code.

Why It Matters:

Without understanding the device tree, your drivers won't load automatically on target hardware. This knowledge is non-negotiable for working with Raspberry Pi custom HATs, SOM boards like STM32MP1 or i.MX, industrial controllers, and camera/motor/sensor boards.

The device tree is the bridge between your driver and real hardware, making your code portable across different board variants.

6. SPI, I2C, GPIO, and Platform Drivers

Once fundamentals are solid, expand into specific driver types that cover most embedded use cases.

SPI Drivers handle high-speed serial peripherals. You'll use spi_driver, spi_device, and spi_transfer structures, register callbacks in probe(), and manage full-duplex transfers. Use cases include DACs, ADCs, IMUs, displays, and radio modules.

I2C Drivers manage lower-speed peripherals using the i2c_driver framework. Learn to use regmap and I2C helper functions to handle SMBus-based devices like temperature sensors, EEPROMs, and power management ICs.

GPIO Drivers become essential for custom boards. Export or control GPIO pins, handle interrupts via irqdomain, and provide custom logic for I/O expanders.

Platform Drivers are used when hardware is memory-mapped rather than bus-based. You'll use the platform_driver framework, map registers using ioremap(), read and write hardware registers directly, and manage clocks, resets, and regulators.

Platform drivers are the backbone of industrial embedded systems, powering everything from custom peripherals to FPGA interfaces.

7. Memory-Mapped I/O & Register Access

Eventually, you'll need to directly interact with hardware registers.

This means learning to read and write hardware registers using ioread32() and iowrite32(), understanding memory barriers to ensure correct ordering, and managing DMA for high-throughput devices.

Why It Matters:

Without this knowledge, you can't write drivers for CAN controllers, Ethernet PHYs, graphics devices, high-speed peripherals, or custom FPGA IP cores. This is where embedded Linux development meets real hardware engineering.

You'll work with memory-mapped registers, understand cache coherency issues, and optimize data transfers for performance-critical applications.

8. Debugging & Testing Workflow

The kernel provides powerful debugging tools that separate novices from professionals.

Use dmesg for logs, ftrace and trace-cmd for timing analysis, printk() for quick debugging, debugfs for user-accessible debugging hooks, and gdb with KGDB for live kernel debugging.

Your Process:

Add debug prints at critical points in your driver's flow. Trace interrupt latency to identify bottlenecks. Verify device tree bindings using of_node properties. Use udevadm to inspect device creation. Write small test applications for /dev/mydevice to validate functionality.

The result? You can isolate issues quickly — from probe failures to IRQ storms — and understand exactly what your driver is doing at any moment.

9. Production-Grade Drivers

Functional drivers are just the beginning. Production-quality drivers require additional engineering.

You'll need to implement power management with suspend and resume hooks, create sysfs attributes for runtime configuration, design proper error paths in probe() and remove() functions, choose appropriate locking strategies, prevent memory leaks, and handle hotplug events gracefully.

Real-World Expectations:

A production driver must be robust enough to handle edge cases, crash-proof under unexpected conditions, efficient with system resources, well-documented for future maintenance, and configurable via device tree or sysfs.

This is the level required for automotive applications, IoT deployments, industrial machinery, and consumer products. The difference between hobbyist and professional driver development lies in this attention to detail.

How This Roadmap Connects to Advanced Embedded Platforms

Modern embedded platforms combine Linux, microcontrollers, industrial networking protocols, and intelligent automation. Device drivers are the invisible backbone enabling this integration.

By mastering Linux device drivers, engineers unlock better integration between microcontrollers and application processors, build reliable sensor and camera pipelines, create custom high-performance interfaces, develop more robust OTA and networking subsystems, and accelerate product iteration with greater platform stability.

This expertise directly strengthens the mission of building scalable, intelligent, and reliable embedded technology for next-generation products. At Hoomanely, we leverage these driver development principles to build advanced embedded platforms that power intelligent automation and seamless hardware-software integration.

Key Takeaways

Linux device drivers bridge the gap between hardware and kernel space, making complex hardware accessible through simple interfaces.

The learning path is clear: start with kernel modules, progress to character drivers and interrupts, master the device tree, then expand into SPI, I2C, GPIO, and platform drivers.

Understanding memory-mapped I/O unlocks advanced hardware control, while debugging skills using ftrace, debugfs, and printk separate competent developers from experts.

Production-ready drivers require power management, error handling, and robustness that goes far beyond basic functionality.

Driver expertise is not optional for building professional embedded platforms — it's the foundation that everything else builds upon.

The journey to mastering Linux device drivers is challenging but incredibly rewarding. Each driver you write deepens your understanding of how hardware and software truly integrate. Start with simple modules, progress systematically through this roadmap, and don't skip the fundamentals. The kernel community has built an incredible framework — your job is to learn its patterns and apply them to solve real problems.