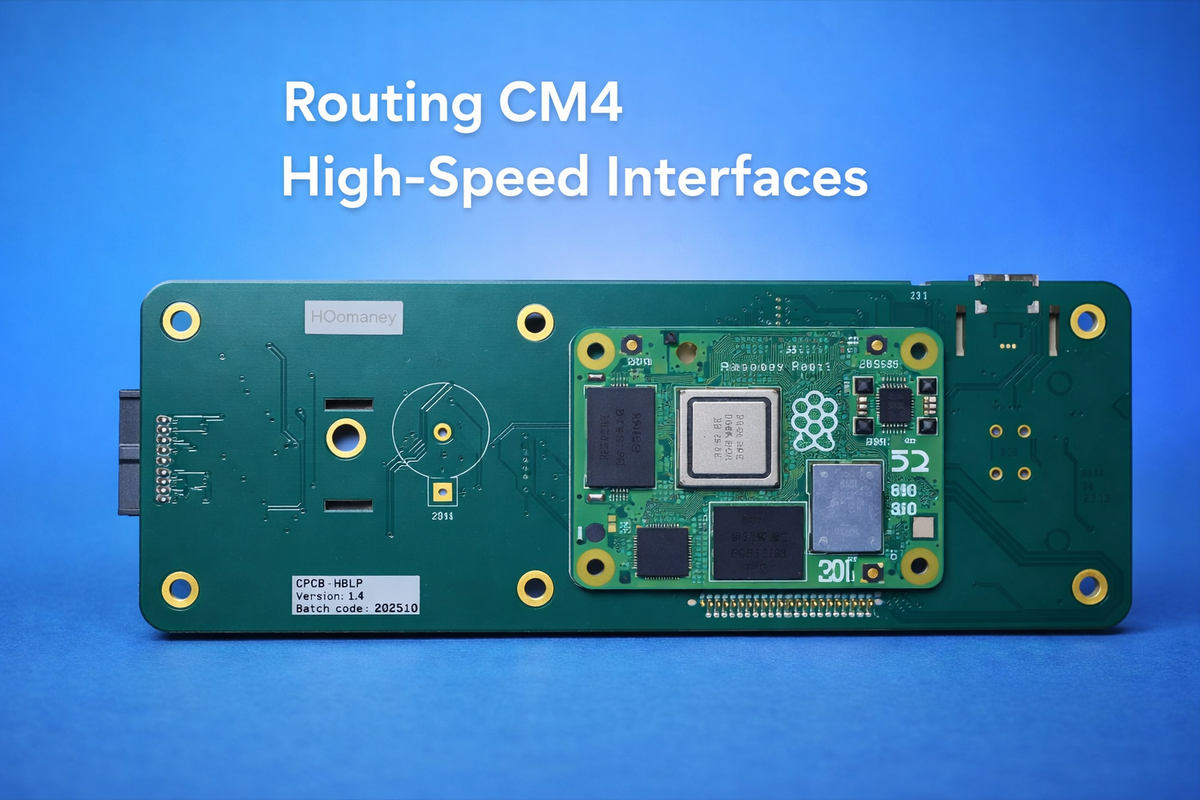

Routing CM4 High-Speed Interfaces

Why USB, PCIe, and the Decision to Punt Are Product-Level Choices, Not PCB Details

1. Introduction: Reframing the Topic

High-speed interface routing on platforms like the Compute Module 4 is often framed as a technical hurdle to be cleared late in design—something to be validated, tuned, and signed off once the “real” product decisions are made. In practice, that framing is backwards.

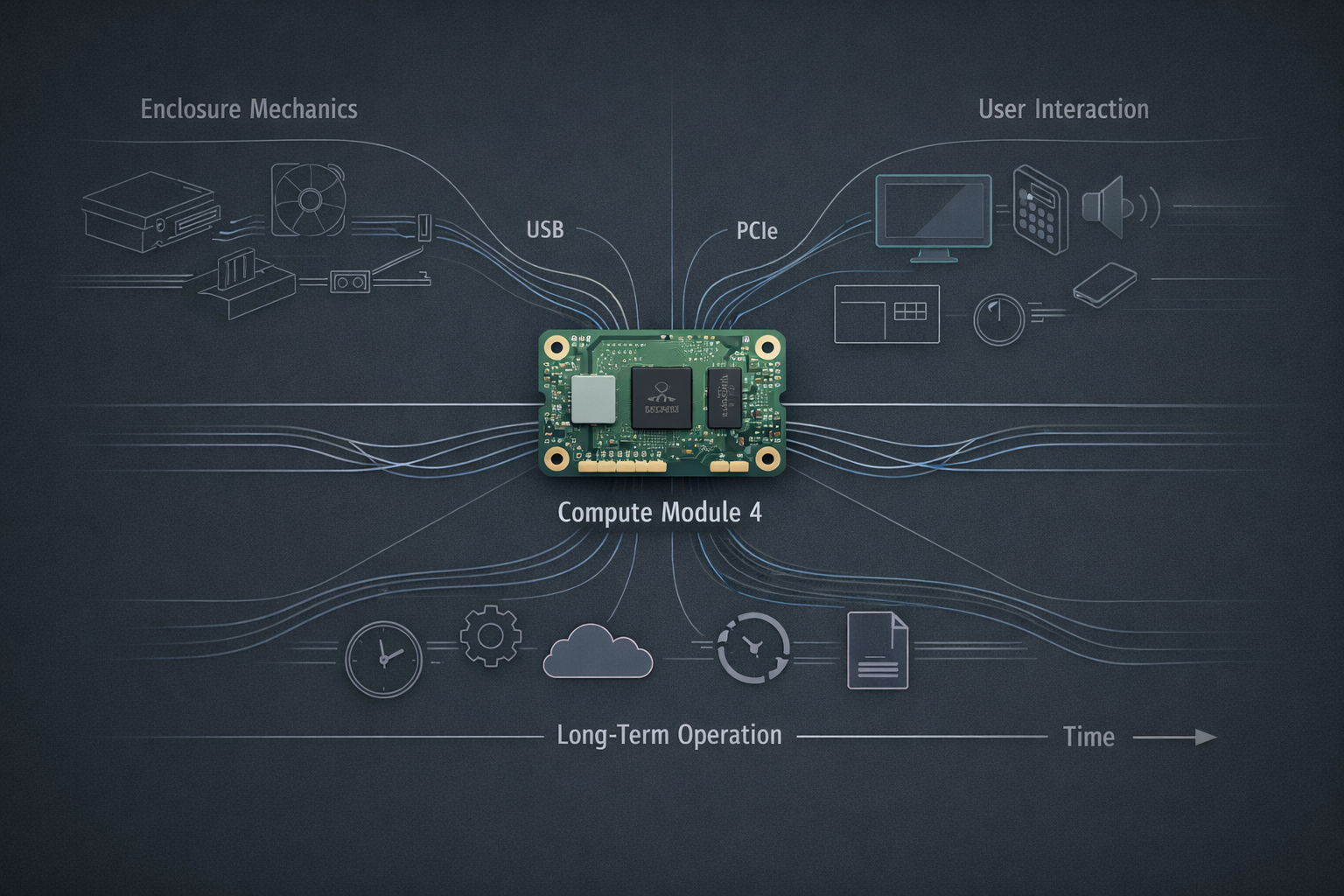

USB and PCIe routing are not post-layout chores or signal-integrity exercises isolated to a PCB file. They are early, structural decisions that quietly define whether a product feels stable or fragile, forgiving or temperamental, robust or strangely inconsistent over time. Long before eye diagrams and compliance reports enter the picture, the choices around which interfaces to expose, how far to push them, and where to deliberately stop have already shaped the product’s future.

On CM4-based systems, this is especially true. The module makes powerful interfaces easily accessible—but availability is not the same as suitability. Treating every exposed lane as an invitation to use it is how complexity sneaks in under the guise of capability.

This article is not about how to route USB or PCIe. It’s about why, when working with CM4-class platforms, routing decisions must be treated as product decisions—decisions that influence reliability, integration, and trust long after the board boots successfully.

2. The Real-World Operating Context

A CM4 rarely lives in the environment its reference designs assume.

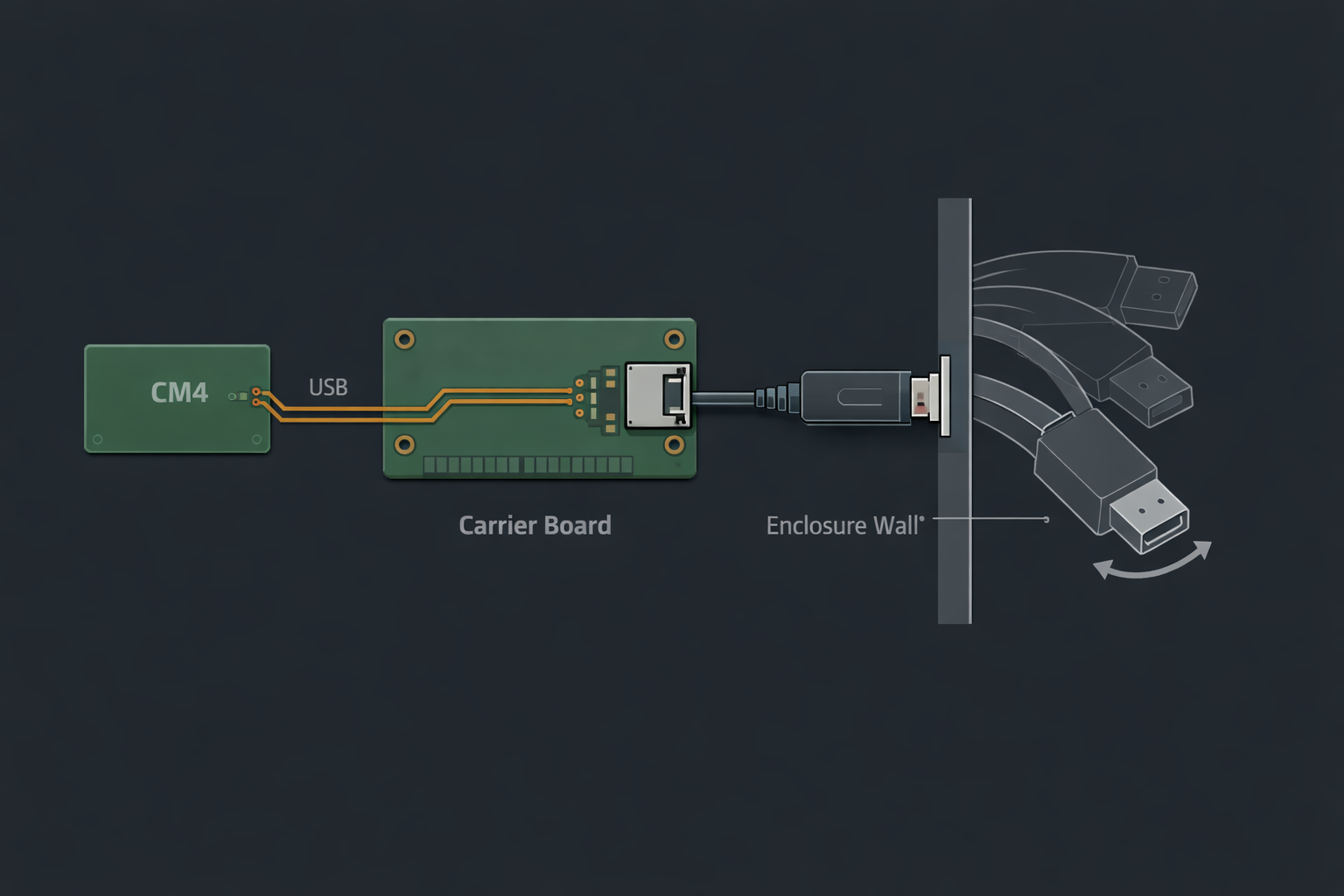

In real products, the carrier board is constrained by enclosure geometry, connector placement, cable exits, and user interaction patterns that repeat thousands of times. USB ports are not static test points—they are insertion cycles, side loads, low-quality cables, and power negotiation with devices that only loosely follow specifications. PCIe lanes are not abstract differential pairs—they are routed through mechanically stressed boards, across connectors that age, and into peripherals that may not share the same grounding assumptions.

Environmental exposure compounds this. Temperature gradients across the board change impedance profiles subtly but persistently. Internal heat sources drift over time. Plastics creep, metals relax, and assemblies settle into states no simulation models precisely capture.

Most importantly, these stresses accumulate quietly. High-speed interfaces rarely fail catastrophically. They degrade into intermittent enumeration issues, bandwidth drops that only show up under load, or behavior that “sometimes” fixes itself after a reboot. By the time users notice, the root cause is already buried in early design decisions.

Designing CM4 interfaces responsibly means grounding every routing choice in this long, unglamorous operating reality—not the first-power-on moment.

3. Primary Engineering Considerations

USB: Ubiquity with Hidden Cost

USB is deceptively familiar. Because it “usually works,” it’s easy to treat it as a solved problem—especially when the CM4 exposes multiple USB paths with minimal ceremony.

In reality, USB is one of the most socially complex interfaces on the board. It negotiates power, data rates, and roles dynamically, often through cables and peripherals of unknown quality. Every centimeter of routing, every connector transition, and every grounding decision shapes how gracefully that negotiation unfolds.

From a system perspective, USB routing decisions are inseparable from mechanical design. Connector orientation determines strain relief. Trace escape patterns influence how much common-mode noise is tolerated. Power distribution choices affect whether devices brown-out silently or fail loudly.

The deeper question isn’t “Can we route USB here?” but “Do we want this interface to be user-facing, user-trusted, and repeatedly exercised?” When the answer is yes, the routing must be conservative—not because the spec demands it, but because the product’s reputation will.

PCIe: Capability with Commitment

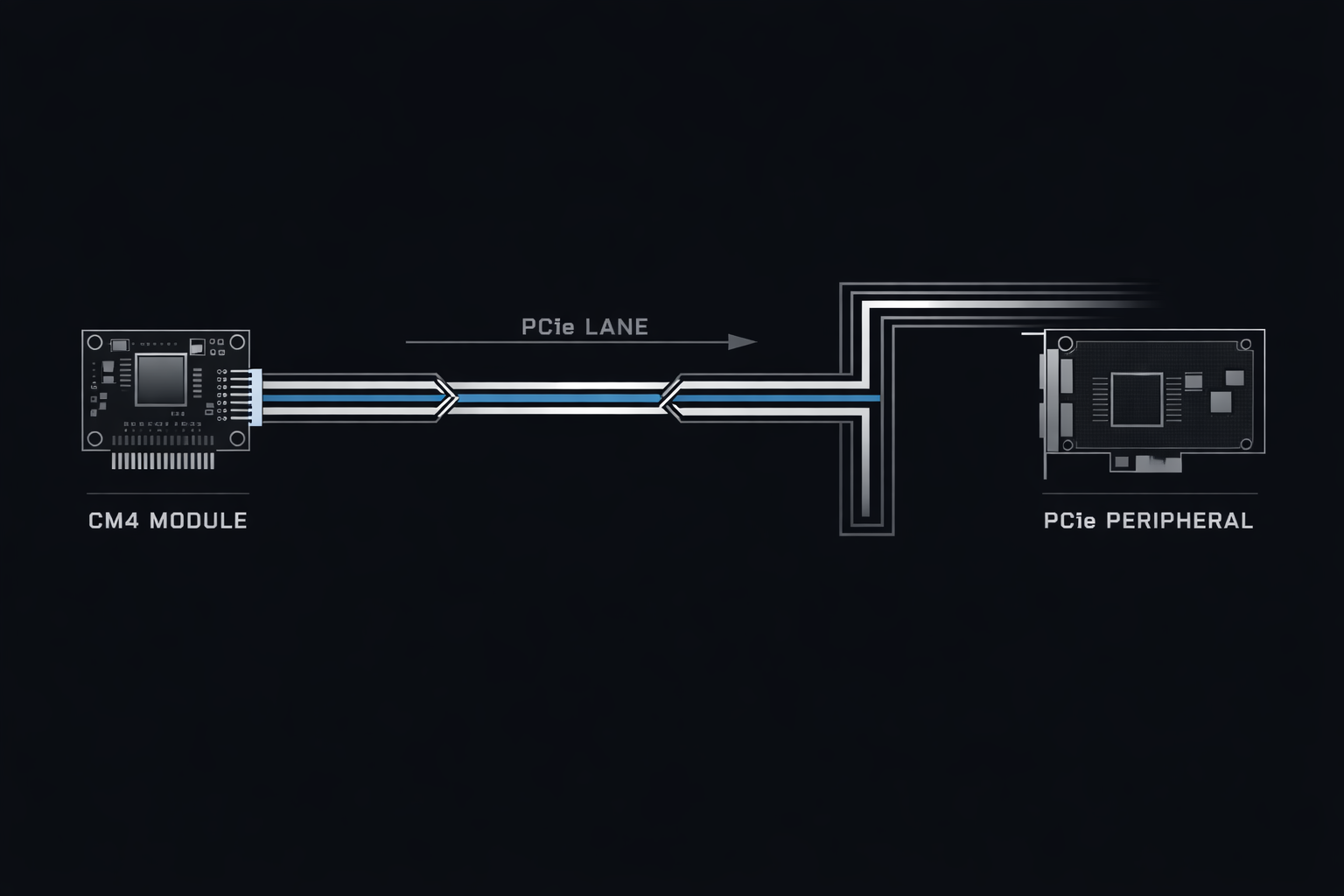

PCIe on CM4 carries a different weight. Exposing a PCIe lane is not just enabling performance—it is committing to a tighter coupling between the SoC, the carrier, and whatever peripheral sits on the other side.

Unlike USB, PCIe assumes shared timing discipline, stable reference clocks, and cleaner power domains. It rewards careful topology and punishes casual integration. Once routed, it becomes one of the hardest interfaces to “de-risk” later, because marginal behavior often looks like software instability or peripheral quirks.

The temptation with PCIe is to treat it as a future-proofing gesture: route it now, decide later what to do with it. In practice, unused or lightly-validated PCIe paths often become liabilities. They occupy routing resources, constrain layer stackups, and quietly complicate EMI behavior—even if no device is populated.

Using PCIe well requires clarity of intent. If the product genuinely benefits from the bandwidth and latency characteristics PCIe offers, the routing should reflect that seriousness. If not, restraint is often the more durable choice.

When to Punt: The Most Underrated Decision

Not every interface needs to be routed. Not every exposed capability needs to become a feature.

Choosing to punt—deliberately deferring or omitting an interface—is not a sign of limitation. It is an assertion of focus. On CM4 designs, this decision often matters more than any trace geometry.

Every high-speed interface you bring out competes for board area, reference integrity, validation effort, and long-term support. Even if it works electrically, it still demands documentation, testing across revisions, and compatibility thinking as the product scales.

Punting early creates room for excellence elsewhere. It simplifies failure modes. It reduces the surface area for unpredictable behavior. Most importantly, it keeps the product’s promise legible: users know what the device is meant to do—and what it isn’t trying to be.

4. Invisible Forces That Shape Design

What ultimately shapes high-speed routing decisions are not the headline constraints, but the quiet ones.

Time is the first. Interfaces that work today must work after thousands of hours of operation, firmware updates, and peripheral swaps. Marginal designs do not announce their weakness immediately—they age into it.

Heat is the second. Even modest temperature differentials across a CM4 carrier can subtly skew high-speed behavior. These effects are rarely dramatic enough to trigger alarms, but they are enough to erode margins over years.

Manufacturing variation is the third. Stackup tolerances, connector plating differences, and assembly stress introduce small deviations that only disciplined designs absorb gracefully. Routing that assumes ideal fabrication quickly reveals its fragility at scale.

Finally, subsystem interaction matters. High-speed lanes do not exist in isolation. They share return paths with power, coexist with radios, and respond to mechanical vibration. The cleanest schematic cannot compensate for a system that treats these interactions as afterthoughts.

5. Designing for Longevity, Not Perfection

Perfection is a lab condition. Longevity is a product condition.

For CM4-based systems, the goal is not maximum theoretical throughput or flawless compliance under pristine setups. The goal is predictable behavior across imperfect realities—cables that bend, users who hot-plug carelessly, environments that fluctuate.

Designing for longevity means accepting that degradation will occur, and shaping it to be controlled and boring. When margins shrink, behavior should remain stable, not erratic. When conditions worsen, failure modes should be obvious, not mysterious.

This mindset shifts how routing decisions are evaluated. Conservative geometry, shorter paths, fewer transitions, and intentional interface selection are not signs of underutilization—they are investments in trust.

6. System Integration Perspective

High-speed routing decisions ripple outward.

Mechanically, they influence enclosure constraints and connector survivability. Electrically, they affect grounding strategies and power integrity. In manufacturing, they shape yield sensitivity and test coverage. In serviceability, they determine how easily issues can be diagnosed—or avoided entirely.

On CM4 carriers, integration discipline matters because the module itself is fixed. The carrier board absorbs the responsibility of making those interfaces feel native, not fragile. Routing becomes the bridge between a powerful compute block and a product that must behave like a cohesive whole.

Seen this way, USB and PCIe are not just interfaces—they are commitments the entire system must uphold.

7. Product Philosophy Reflection

There is a philosophy embedded in how interfaces are routed.

Choosing restraint over maximal exposure signals confidence in the product’s purpose. Designing margins that favor stability over spectacle reflects respect for users who rely on the device long after the novelty fades. Treating routing as a system-level decision acknowledges that engineering does not end at bring-up—it extends into years of quiet operation.

This level of rigor is rarely visible to users, but it is deeply felt. Products that “just work” earn trust not through marketing claims, but through the absence of friction. That absence is engineered.

8. Conclusion: Engineering That Holds Up Over Time

Routing CM4 high-speed interfaces is not a checkbox exercise. It is a foundational act that shapes how a product behaves, ages, and is perceived.

USB, PCIe, and the decision to punt are levers of intent. Used thoughtfully, they reduce complexity, preserve reliability, and align the hardware with its real purpose. Used casually, they introduce long-tail risks that no amount of post-hoc validation can fully erase.

Thoughtful engineering is not about exploiting every capability—it is about choosing the right ones, and supporting them with discipline. In the long run, that restraint is what allows products to outlast trends, revisions, and shortcuts—and quietly do their job, year after year.