Seeing Heat: Thermal Characterization Strategies for Dense PCB Designs

Introduction: Making the Invisible Visible

Our vBus modules represent a feat of extreme integration, condensing high-performance processors, switching power regulators, wireless transceivers, and sensor interfaces into PCBs measuring merely a few square inches. This density introduces a fundamental challenge: heat generation is concentrated, thermal gradients are steep, and component reliability hinges on a precise understanding of exactly how heat flows through the system. We treat thermal characterization not as guesswork, but as a rigorous science of measurement, analysis, and validation that transforms thermal behavior from a mystery into actionable engineering data. By instrumenting prototypes to isolate hotspots and implementing targeted optimizations, we ensure that every product operates reliably within its thermal limits across the entire operational envelope. Today, I am sharing the methodology—the tools, techniques, and systematic approaches—that allows us to deliver thermally robust designs on the first iteration.

Understanding Thermal Density

Power Concentration in Compact Designs

Dense boards create thermal challenges that low-density designs avoid:

Heat Generation Density: Total power dissipation divided by board area:

- Typical consumer electronics: 0.1-0.5 W/cm²

- Our high-performance modules: 1-3 W/cm²

- Challenge: 5-10× higher thermal density

Component Proximity: Tight spacing means limited thermal isolation:

- Adjacent hot components create cumulative heating

- Temperature of component A influenced by nearby component B

- Thermal management requires system-level thinking, not just per-component analysis

Limited Heatsink Real Estate: Compact boards constrain thermal solutions:

- Heatsinks compete for PCB area with components

- Enclosure contact points limited

- Forced airflow often impractical (noise, power, complexity)

Goal: Achieve reliable operation through intelligent thermal design validated by comprehensive characterization.

Instrumentation: Measuring Temperature Accurately

Thermocouple Placement Strategy

Thermocouples provide direct, real-time temperature measurement:

Type K Thermocouples: Standard choice for electronics (−200°C to +1350°C range, ±2.2°C accuracy)

Attachment Method: Critical for accurate readings:

- Epoxy mounting: Thermally conductive epoxy (e.g., Arctic Silver adhesive) bonds thermocouple bead to component package

- Placement precision: Center of package top surface for ICs, thermal pad for power components

- Wire routing: Minimize thermal conduction through wires—route away from hot zones

Strategic Sensor Placement:

Primary Hotspots:

- Main processor (highest continuous power dissipation)

- Switching regulators (combination of conduction and switching losses)

- Power MOSFETs (I²R heating under load)

- Wireless power amplifiers (RF transmission duty cycle dependent)

Thermal Gradient Mapping:

- PCB corners (coolest zones typically)

- Mid-board locations (intermediate temperatures)

- Between closely-spaced hot components (mutual heating analysis)

Ambient Reference: One thermocouple measuring ambient air temperature near board (essential for thermal rise calculations)

Typical Instrumentation: 8-12 thermocouples per prototype board covering critical components and thermal gradient mapping points.

Data Acquisition Systems

Multi-Channel DAQ: USB-connected thermocouple interface:

- 8-16 channel simultaneous sampling

- 1-10 Hz sample rate (captures thermal transients)

- PC logging software with real-time graphing

Software Logging: Captures temperature vs. time:

- Timestamp-synchronized across all channels

- CSV export for post-processing and analysis

- Real-time alerts when temperatures exceed thresholds

Test Duration: Thermal soak tests run 30-60 minutes:

- Allows system to reach thermal equilibrium

- Captures steady-state temperatures

- Reveals slow thermal drift or cumulative heating

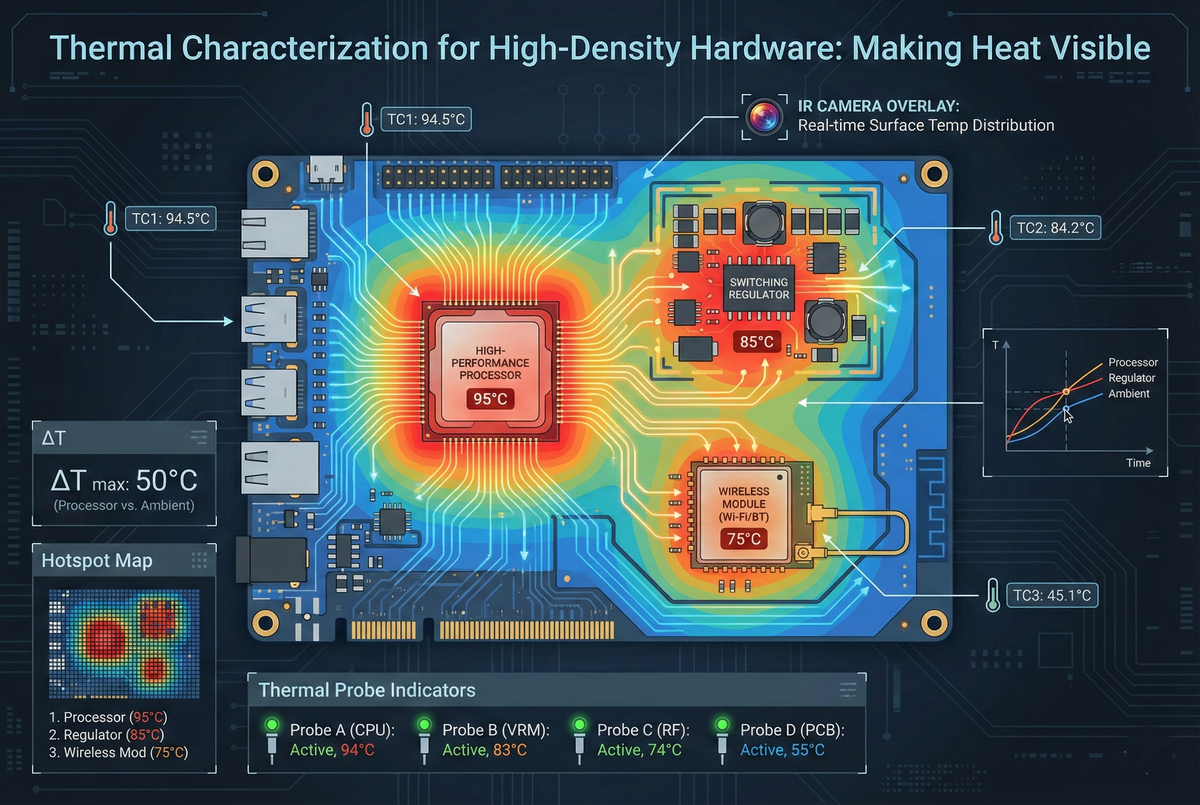

Infrared Thermal Imaging

Seeing the Complete Thermal Picture

Thermocouples provide point measurements; thermal cameras reveal spatial distribution:

FLIR/Seek Thermal Cameras: 320×240 to 640×480 resolution infrared sensors:

- Temperature range: −40°C to +550°C (covers all electronic components)

- Accuracy: ±2°C or ±2% (adequate for hotspot identification)

- Frame rate: 9-60 Hz (captures thermal transients)

Imaging Procedure:

Board Orientation: Horizontal placement, camera positioned overhead:

- Perpendicular viewing angle (minimizes emissivity variation effects)

- Consistent distance (enables calibration and comparison)

- Controlled ambient environment (minimize background IR sources)

Emissivity Compensation: Different surfaces radiate IR differently:

- Black soldermask: ε ≈ 0.95 (good emitter, accurate temperature reading)

- Bare copper: ε ≈ 0.07 (poor emitter, reads artificially low)

- IC packages: ε ≈ 0.85-0.95 (plastic/epoxy—good emitter)

- Solution: Apply uniform black paint or tape to metal surfaces for accurate measurement, or use known-emissivity reference points for calibration

Thermal Image Capture:

- Initial power-on: Capture thermal transient as system heats up

- Steady-state: Capture after 30+ minutes of operation at max load

- Thermal cycling: Capture during load transitions (idle → full load → idle)

Analysis: Thermal images reveal:

- Absolute hotspots: Peak temperatures (where are they?)

- Thermal gradients: How rapidly temperature changes across PCB

- Unexpected heat sources: Components dissipating more than expected

- Thermal coupling: Heat transfer patterns between components

Comparative Thermal Analysis

Before/After Validation: Thermal imaging enables quantitative optimization assessment:

Baseline capture: Initial design with suspected thermal issues

Implement fix: Add thermal vias, heatsink, copper pour, etc.

Re-capture: Same test conditions, same camera settings

Compare: Side-by-side thermal images + peak temperature comparison

Quantifiable improvement: "10°C reduction in processor temperature after adding thermal via array"—objective validation of design change effectiveness.

Hotspot Identification and Root Cause Analysis

Defining Thermal Limits

Each component has maximum junction temperature (T_j,max):

- Consumer-grade ICs: 85°C to 100°C typical

- Industrial-grade: 125°C common

- Automotive-grade: 150°C rated

Design Target: Maintain junction temperature ≤ (T_j,max − 20°C) safety margin:

- Accounts for worst-case ambient (40°C indoor typical)

- Provides reliability margin (lower temperature = longer lifetime)

- Accommodates measurement uncertainty

Example: Processor rated for 85°C junction temperature:

- Target max measured case temperature: 65°C

- At 40°C ambient: 25°C thermal rise

- Provides 20°C margin to absolute limit

Systematic Hotspot Diagnosis

When measurements exceed targets, systematic analysis determines cause:

Power Dissipation Verification:

- Measure actual current consumption (compare to datasheet typical)

- Calculate power: P = V × I

- Higher than expected? Investigate why (unexpected load, incorrect configuration, component defect)

Thermal Resistance Analysis:

- Thermal rise: ΔT = T_measured − T_ambient

- Power dissipation: P (measured)

- Effective thermal resistance: R_θ = ΔT / P

- Compare to expected thermal resistance (datasheet θ_JA or calculated PCB thermal resistance)

- High R_θ indicates inadequate heat spreading or transfer

Thermal Path Audit:

- Component → PCB copper (adequate pad area? thermal vias present?)

- PCB copper → internal planes (via count sufficient?)

- PCB → ambient air (surface area? airflow?)

- PCB → enclosure (thermal interface material present? contact pressure adequate?)

Diagnosis Example: Switching regulator measuring 85°C (target: 70°C)

- Power dissipation: 2.5W measured (datasheet typical: 2.0W)

- Investigation reveals: Input voltage higher than datasheet typical test conditions

- Thermal resistance: (85-40)/2.5 = 18°C/W

- Datasheet θ_JA: 35°C/W with minimal copper

- Conclusion: Inadequate copper area under device—thermal spreading insufficient

Thermal Fixes: Targeted Solutions

Copper-Based Solutions

Thermal Via Arrays: Plated through-holes conduct heat from component to opposite PCB side and internal planes:

Implementation: Grid of vias under component thermal pad:

- Via diameter: 0.3mm typical

- Via spacing: 0.5-1mm pitch

- Quantity: 20-40 vias for typical QFN/power packages

- Effectiveness: 40-60% reduction in thermal resistance

Design consideration: Thermal vias must connect to internal ground or power planes (large copper area for heat spreading)—isolated vias provide minimal benefit.

Copper Pour Expansion: Increase copper area around hot components:

- Ground plane flooding around component

- Wide power traces (double as heat spreaders)

- Top and bottom layer copper connected via stitching vias

- Effectiveness: 20-30% temperature reduction for moderately hot components

Heatsink Integration

Surface-Mount Heatsinks: Aluminum or copper extruded profiles:

Attachment: Thermally conductive adhesive or thermal tape:

- Apply to component package top surface

- Heatsink increases effective surface area by 10-30×

- Natural convection cooling enhanced

Sizing: Heatsink thermal resistance (°C/W) selected based on:

- Component power dissipation

- Target temperature reduction

- Available board space

Example: 2W component, target 20°C reduction:

- Required heatsink R_θ: 20°C / 2W = 10°C/W

- Select heatsink with specified thermal resistance ≤10°C/W

Effectiveness: 30-50°C temperature reduction typical with properly sized heatsink

Enclosure Thermal Management

Thermal Pads to Enclosure: Soft silicone thermal pads transfer heat from PCB to metal enclosure:

Implementation:

- Identify hottest component location

- Position thermal pad between component and enclosure inner surface

- Enclosure becomes large thermal mass and radiating surface

- Effectiveness: 15-25°C reduction when PCB-to-enclosure thermal path established

Enclosure Material Selection: Metal preferred over plastic:

- Aluminum: Good thermal conductivity (205 W/m·K)

- Steel: Moderate conductivity (50 W/m·K)

- Plastic: Poor conductivity (0.2 W/m·K)

- Metal enclosures dissipate heat, plastic enclosures insulate

Component-Level Optimization

Power Supply Efficiency: Switching regulators generate heat proportional to losses:

- Higher efficiency = less heat

- Select high-efficiency buck converters (>90% typical)

- Optimize operating point (efficiency varies with load)

Component Derating: Operate components below maximum ratings:

- Power MOSFETs: Use device rated for 2× expected current (lower R_DS_on)

- Regulators: Don't operate at absolute max current (reduces dissipation)

- Lower operating stress = lower temperature = longer life

Layout Optimization: Component placement influences thermal behavior:

- Separate hot components (prevent mutual heating)

- Position hot components near board edges (better heat dissipation)

- Orient tall components to minimize shadowing (if airflow present)

Validation Testing Protocol

Thermal Stress Testing

Maximum Load Test: Operate system at worst-case power dissipation:

- All peripherals active

- Maximum processing load (CPU at 100%)

- Continuous wireless transmission (if applicable)

- Duration: 60+ minutes

Elevated Ambient Test: Operate in temperature chamber:

- Set ambient to max rated temperature (typically 40-50°C for consumer products)

- Run maximum load test

- Validate junction temperatures remain within limits

Thermal Cycling: Repeated temperature transitions:

- Power on → thermal equilibrium → power off → cool down

- Repeat 10-20 cycles

- Validates solder joint integrity (thermal expansion/contraction stress)

- Confirms no thermal runaway or cumulative heating issues

Pass/Fail Criteria

Temperature Limits: All components remain within:

- Absolute maximum: T_j < T_j,max (component datasheet limit)

- Design target: T_j < T_j,max − 20°C (reliability margin)

Thermal Gradient Limits: Temperature variation across board:

- <30°C gradient between hottest and coolest areas (excessive gradient indicates poor heat spreading)

Long-Term Stability: Temperatures stabilize within test duration:

- No continuous temperature climb (indicates inadequate cooling)

- Thermal equilibrium reached (steady-state validation)

Documentation and Knowledge Transfer

Thermal Test Reports

Comprehensive documentation captures:

- Test conditions (ambient temp, load profile, test duration)

- Instrumentation setup (thermocouple locations, camera settings)

- Measured data (temperature vs. time plots, thermal images)

- Analysis (hotspot identification, thermal resistance calculations)

- Conclusions (pass/fail assessment, recommendations)

Thermal Image Annotation: Annotated thermal images show:

- Peak temperature locations marked

- Temperature values labeled

- Hot zones highlighted

- Reference scale and timestamp

Thermal Design Guidelines

Lessons learned feed into design standards:

- Minimum thermal via count for power components (documented in footprint creation guidelines)

- Preferred heatsink part numbers and thermal resistances

- Enclosure thermal interface strategies

- Component placement rules for thermal management

Designer Training: New engineers learn from characterized designs:

- Review thermal reports from previous products

- Understand which design decisions impacted temperatures

- Apply proven thermal strategies to new designs

Conclusion: Thermal Excellence Through Measurement

Thermal characterization transforms thermal design from guesswork into engineering discipline. By systematically instrumenting prototypes with thermocouples, capturing spatial thermal distributions with infrared cameras, identifying hotspots through analysis, and implementing targeted fixes validated through comparative testing, we ensure that every vBus module operates reliably within its thermal envelope.

The investment in characterization pays dividends throughout product lifecycle: early hotspot identification enables design corrections before volume production, validated thermal margins ensure field reliability, and documented thermal behavior informs future designs. This isn't reactive troubleshooting—it's proactive thermal engineering that builds reliability in from the start.

As our modules push density boundaries and power envelopes expand, thermal characterization remains essential infrastructure. The tools are accessible (thermocouples, thermal cameras), the methodology is systematic, and the results are quantifiable. Every degree matters when components operate near their limits, and measurement is how we ensure those limits are never exceeded.

This is engineering rigor applied to invisible phenomena—making heat visible, making behavior predictable, and making reliability achievable through systematic validation.