Signal Integrity Across Mixed Boards: Engineering Predictability Into vBus PCBs

Introduction: Signal Integrity as a System Property

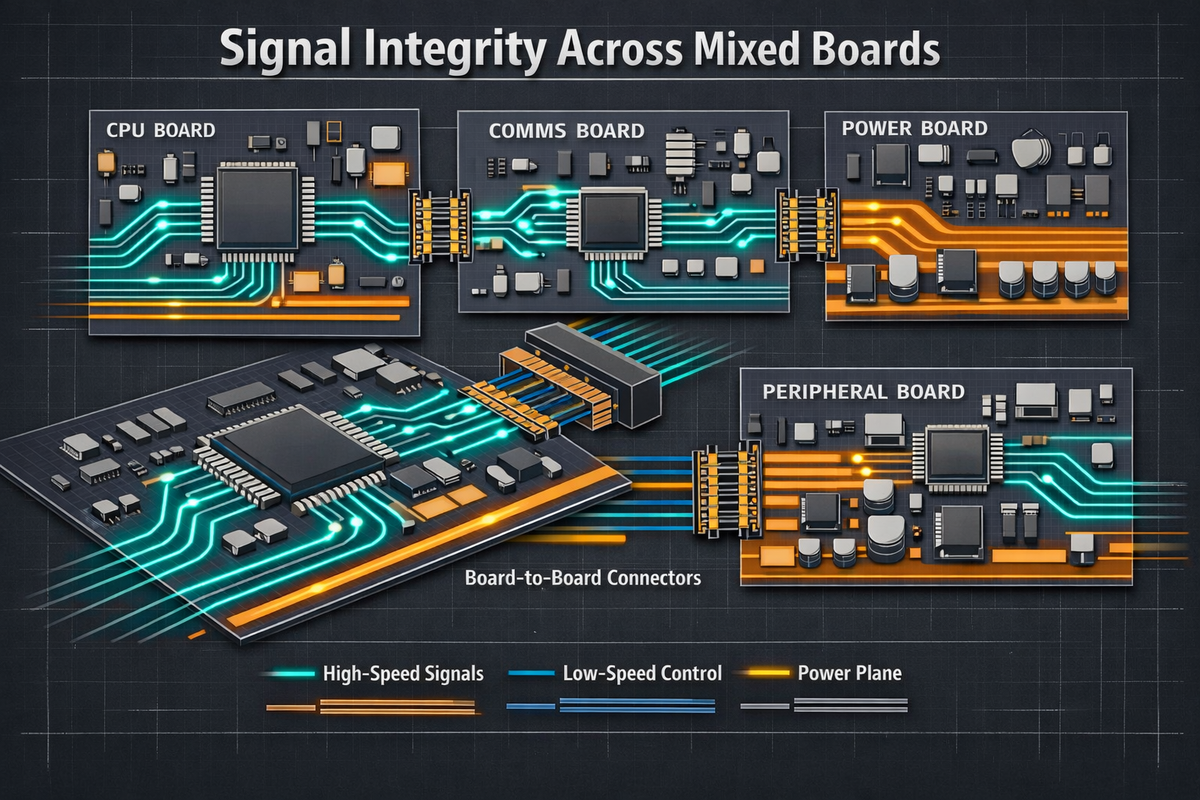

In the world of hardware development, "prototype" is often synonymous with "experimental." It implies a level of instability that is acceptable for a proof-of-concept but disastrous for a product. However, in the vBus ecosystem—where CPU SoMs, Power SoMs, Communication modules, and industrial peripherals must coexist in compact enclosures—we cannot afford the luxury of experimental instability.

Signal integrity (SI) is rarely lost at a single trace or a specific via. In modular systems, it degrades at the boundaries. It fails at the transition between the high-current power domain and the logic domain; it collapses at the board-to-board connector; it unravels when high-speed edge rates encounter the uncontrolled impedance of a generic pin header.

For the vBus architecture, signal integrity is not merely a routing concern—it is a system-level discipline. Our goal has never been to "fix SI later" during a board re-spin. Instead, vBus boards are designed so that signal behaviour is predictable from the very first power-on. That predictability comes from treating signal integrity as a shared responsibility across connectors, stackups, power distribution networks (PDN), and the physical layout of components.

This article outlines the deep engineering strategies we use to ensure signal integrity across mixed boards. We do this without relying on "heroics," without post-hoc tuning, and without leaving success to chance.

The Physics of the Substrate: Stackup and Materials

The foundation of any signal integrity strategy is the board itself. Before a single component is placed, the stackup dictates the behaviour of electromagnetic fields. In vBus designs, we treat the PCB not as a mechanical carrier for parts, but as a precise electrical component.

Beyond Generic FR-4: Material Science

Standard FR-4 is a cost-effective default, but it is chemically inconsistent. For low-speed logic, this is negligible. For interfaces like USB 3.0, PCIe, or Gigabit Ethernet running across vBus modules, the variations in Dielectric Constant (Dk) and Dissipation Factor (Df) can act as a low-pass filter, attenuating high-frequency content and closing the signal eye.

In vBus prototypes involving high-speed links, we specify materials with tighter weave control and known dielectric properties. We must account for the Fiber Weave Effect. Standard PCB glass cloth (like 1080 or 7628 styles) has gaps between the glass bundles. If a high-speed differential pair runs parallel to the weave, one leg of the pair might travel over glass (Dk≈6.0) while the other travels over resin (Dk≈3.0). This creates a propagation delay mismatch (skew) that converts differential mode signal into common-mode noise. To mitigate this, we employ "zigzag" routing or specify spread-glass prepregs to homogenise the substrate environment.

The Sacred Reference Plane

Every high-speed signal in a vBus design requires an uninterrupted reference plane directly adjacent to its signal layer. This is non-negotiable.

We design stackups to minimise the distance (h) between the signal and the reference. This proximity serves two critical functions:

- Confinement of Fields: It keeps the electromagnetic fields tightly coupled between the trace and the plane, reducing the likelihood of the fields spreading out and coupling to neighbouring traces (crosstalk).

- Impedance Control: It allows us to achieve 50Ω or 100Ω differential impedance with manageable trace widths.

If a stackup forces us to reference a power plane instead of a ground plane, we ensure that the power plane is effectively an AC ground. However, the preference is always Ground-Signal-Ground (GSG) stackups where the reference potential is identical to the shielding potential.

The Grounding Philosophy: Partitioning Over Splitting

One of the most dangerous myths in mixed-signal design is the idea of "splitting the ground plane." Engineers often physically cut the copper between the "Analogue Ground" and "Digital Ground" to keep them separate. In the vBus architecture, we view physical ground splits as a major hazard.

The Return Path Dilemma

Current always flows in a loop. At low frequencies (DC to a few kHz), return current follows the path of least resistance—usually the shortest geometric line. However, at high frequencies (above a few kHz), return current follows the path of least inductance. This path is directly underneath the signal conductor.

If we physically split a ground plane and route a trace across that void, the return current cannot flow underneath the trace. It is forced to travel around the split to find a bridge. This creates a massive current loop area. In antenna theory, a large current loop creates a highly efficient radiator. By splitting the ground, we turn our PCB into a slot antenna, radiating EMI and absorbing external noise.

Virtual Partitioning

Instead of cutting copper, vBus boards use Component Partitioning.

- We place noisy circuits (Buck converters, motor drivers) on one side of the board.

- We place sensitive analogue circuits (ADCs, sensors) on the other.

- We maintain a single, unified, solid ground plane underneath both.

Because high-frequency currents stick tightly to the copper directly under their signal traces, the noise from the buck converter effectively stays in the "noisy" zone without needing a physical cut. The physics of inductance keeps the signals separated virtually. If a split is absolutely necessary for isolation standards (e.g., mains voltage), we use optocouplers or transformers to bridge the gap; no copper trace ever crosses a void.

Board-to-Board Connectors as Transmission Lines

In modular systems like vBus, the board-to-board connector is traditionally the "weakest link" for signal integrity. It represents a discontinuity in the transmission line where impedance can fluctuate wildly.

Pin Assignment Strategy

We do not assign connector pins based on the convenience of routing; we assign them based on signal return requirements.

- The GSG Rule: For every high-speed single-ended signal, there must be at least one adjacent Ground pin.

- The GSSG Rule: For differential pairs, we surround the pair with ground (Ground-Signal-Signal-Ground).

This pinout mimics the coaxial structure of the PCB routing (signal surrounded by metal) as it travels vertically through the connector. It minimises the inductive loop through the interconnect.

Impedance Discontinuities

Even with perfect pinouts, the physical pads of a connector add parasitic capacitance. On vBus boards, we often employ voiding on the reference layers directly beneath the connector signal pads. By removing the ground copper on Layer 2 directly under the Layer 1 connector pad, we increase the distance to the reference, thereby reducing the excess capacitance. This technique helps maintain the 50Ω impedance target right up to the metal contact, preventing signal reflections.

Routing Strategy: Managing Energy Fields

Once the stackup and interconnects are defined, routing begins. We view routing not as "connecting dots" but as guiding electromagnetic waves.

Crosstalk and the 3W Rule

In the dense real estate of a vBus module, traces are often forced close together. This invites Crosstalk—the capacitive and inductive coupling of energy from an aggressor trace to a victim trace. To mitigate this, we adhere to the 3W Rule: the distance between the centres of two aggressive high-speed traces should be at least three times the width of the traces. This reduces coupling flux by approximately 70%.

For critical clock lines or extremely sensitive analogue inputs, we may use a Guard Trace—a ground trace running between signals. However, guard traces are a double-edged sword; if they are not stitched to the main ground plane at regular intervals, they can become resonant antennas. In vBus layouts, we prioritize spacing (3W) over guard traces unless absolutely necessary.

Differential Pair Management

For differential signals (USB, Ethernet), symmetry is more important than absolute length.

- Phase Matching: It is not enough for the Positive (P) and Negative (N) traces to be the same total length. They must be phase-matched at every turn. If the P trace travels 5mm longer than the N trace through a bend, the signal briefly becomes common-mode noise. We use small "phase bumps" immediately near the mismatch to correct this locally.

- Dynamic Skew: We ensure that the fiber weave effect mentioned earlier doesn't de-skew our perfectly matched lines.

Power Integrity as a Signal Integrity Multiplier

You cannot have clean signals without a clean reference. When a digital IC switches, it draws a sudden gulp of current (di/dt). If the Power Distribution Network (PDN) has high impedance, this current demand causes the voltage rail to dip (ripple). This ripple propagates through the driver and appears as jitter on the output signal.

Target Impedance Design

vBus designs treat the power rail as a frequency-dependent impedance profile.

- VRM (Voltage Regulator Module): Handles low-frequency current demands (DC to ~10 kHz).

- Bulk Capacitors: Handle the mid-range (10 kHz to ~1 MHz).

- Ceramic Decoupling: Handles high frequencies (1 MHz to ~100 MHz).

- Plane Capacitance: The capacitance formed by the Power and Ground planes sandwiching the dielectric handles the ultra-high frequencies (>100 MHz).

We select capacitors not just for their bulk value (uF), but for their ESR (Equivalent Series Resistance) and ESL (Equivalent Series Inductance). We place the smallest, lowest-inductance capacitors closest to the IC power pins to provide immediate energy for edge transitions. This ensures that the reference voltage remains stable even during aggressive switching, preserving the vertical opening of the signal eye diagram.

Validation: Simulation and Measurement

The "behaviour" of a prototype is the final exam, but we do not wait for the hardware to arrive to know the answer.

Pre-Layout Simulation

Before a route is finalised, we use IBIS (Input/Output Buffer Information Specification) models provided by silicon vendors. We simulate the critical nets to determine:

- Do we need series termination resistors to dampen ringing?

- What is the maximum allowable trace length before signal degradation occurs?

- Is the drive strength of the output buffer sufficient for the capacitive load?

Post-Layout Validation

Once the board is routed, we use 2.5D or 3D field solvers to analyse coupling. We look for "accidental" impedance changes—for example, a trace passing over a void in the ground plane that was missed by the human eye.

Lab Verification

When the vBus prototype arrives, we validate the simulation against reality using TDR (Time Domain Reflectometry). TDR allows us to send a pulse down the line and watch the reflections. We can literally "see" the connector, the via, and the trace segment on the oscilloscope screen, identifying exactly where impedance mismatches occur.

Conclusion: Signal Integrity as Confidence

Signal integrity is not a dark art; it is physics. It is the rigorous application of Maxwell’s equations to copper and fibreglass.

In the vBus ecosystem, we do not view SI as a checklist item to be addressed at the end of the design cycle. It is an architectural constraint that informs every decision—from the selection of the laminate material to the assignment of a connector pin, to the placement of a decoupling capacitor.

By treating signal integrity as a system property, we ensure that our prototypes function not just as "proofs of concept," but as "proofs of manufacturability." We eliminate the "ghosts in the machine"—the random resets, the data corruption, the inexplicable EMI failures—before they ever manifest.

When signal integrity is engineered in—through robust stackups, disciplined return paths, and proactive power integrity—prototypes stop being experiments. They become reliable, predictable, production-ready assets. This discipline shortens development cycles, accelerates integration, and ultimately, builds the engineering confidence required to ship world-class hardware.