Teaching Machines to Understand Movement: Dog Behavior Classification with IMU Data

Introduction

Dogs communicate a lot-just not in words. How they tilt their head, shake their neck, scratch an itch, drink water, or suddenly sprint toward the door often carries more health and behavioral information than their bark. At Hoomanely, we’ve always believed that the next leap in pet health will come from understanding these subtle patterns at scale. That’s why our team has been building a neck-band IMU–based behavior classification system that can automatically read motion signals and label what a dog is doing in real time.

This post walks through the technical journey of how we process high-frequency accelerometer and gyroscope data, break it into sliding windows, feed it into a CNN + BiGRU model, and achieve good validation accuracy on behaviors like shaking, drinking, walking, running, and scratching. It’s a challenging problem-because dogs move unpredictably-but the results open the door to smarter health monitoring, early illness detection, and a deeper understanding of everyday routines.

Why Dog Behavior Classification Is Uniquely Hard

Human activity recognition is a mature field-step tracking, fall detection, cycling classification, and sleep estimation have all existed for years. But dogs break all the assumptions these models rely on:

1. Dogs do not move like humans.

Human movement is structured and periodic. Dogs… are chaos. They shake violently, sprint in short bursts, scratch with asymmetric movements, or suddenly freeze for long periods.

2. Orientation of the device constantly changes.

Neck-bands rotate freely as dogs play, jump, or roll. This means the IMU axes rarely stay aligned the same way for more than a few seconds.

3. Many behaviors look similar in raw data.

Drinking vs licking

Scratching vs shaking

Walking vs playful short-burst hopping

Even humans struggle to differentiate some of these without context.

4. Signals are short and high-frequency.

A neck shake lasts 250–700 ms. Drinking happens in rhythmic bursts. These micro-behaviors require high sample rates to capture correctly.

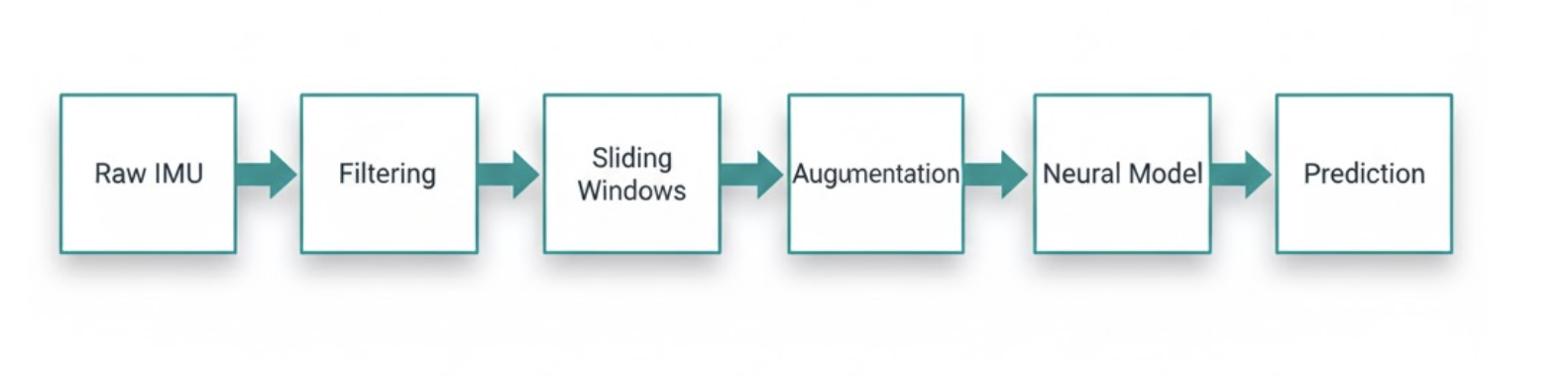

Data Pipeline: From Raw IMU Streams to Training Windows

We collect IMU data from a 9-axis sensor (accelerometer + gyroscope + magnetometer), but our first version uses only six channels: (ax, ay, az, gx, gy, gz) sampled at 100–120 Hz on the neck-band.

1. Preprocessing the Streams

- Downsample or upsample to a consistent frequency (e.g., 100 Hz).

- Apply a low-pass filter (Butterworth, 20–25 Hz cutoff) to remove high-frequency noise.

Normalize each axis with:

x_norm = (x - mean) / std

2. Sliding Window Segmentation

We frame the IMU signal into overlapping windows:

- Window size: 1.5 seconds

- Step size: 0.5 seconds (for 66% overlap)

Each window becomes a 100 Hz × 150 samples × 6 channels tensor.

3. Labeling Strategy

The most time-consuming part is manual labeling. We synchronise IMU logs with video recordings using:

- Timestamp alignment

- Motion peak syncing

- Annotators tagging segments in playback

This gives us a dataset of behaviors such as:

- Walking

- Running

- Shaking

- Scratching

- Drinking

- Lying down

- Eating

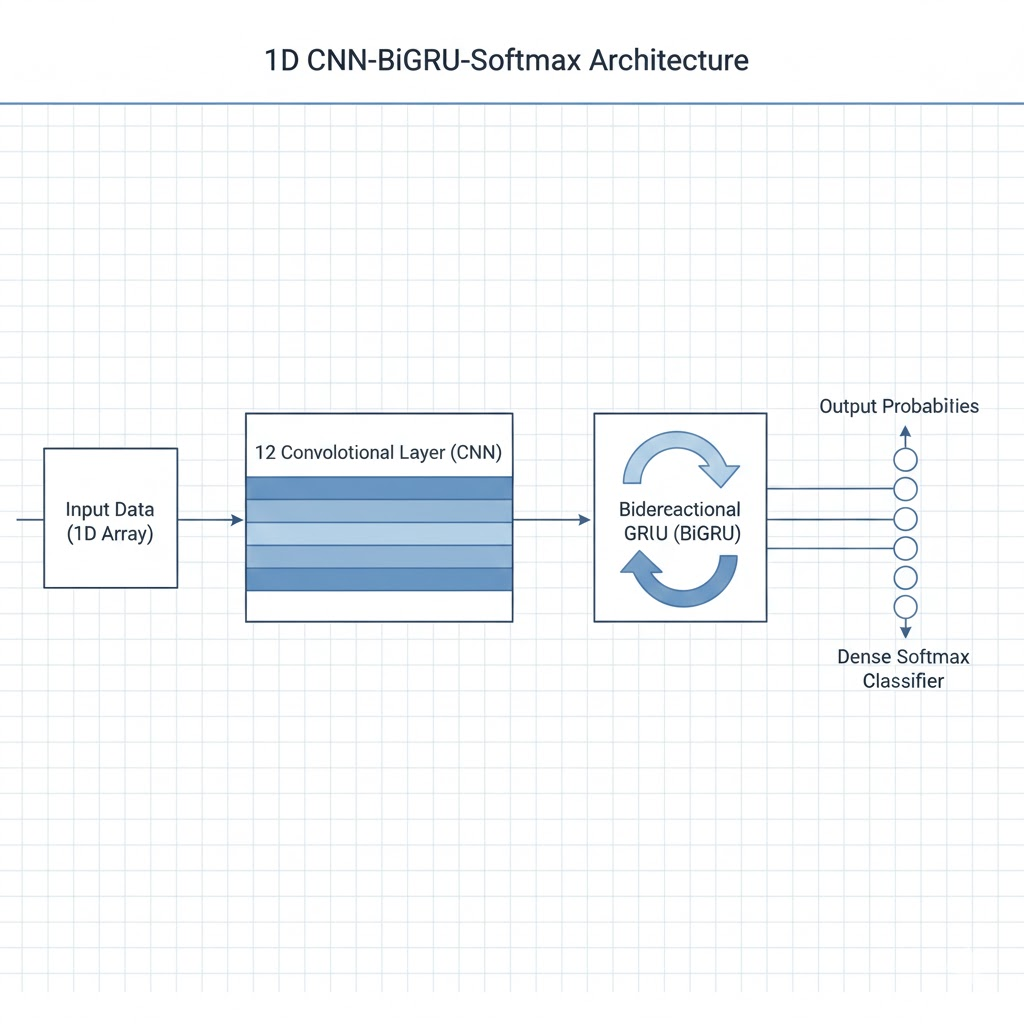

Model Architecture: CNN for Local Patterns + BiGRU for Temporal Understanding

The core idea is simple:

CNNs extract short-range motion patterns, while GRU layers learn longer temporal dependencies.

Overall Architecture

- Input: (150 samples, 6 channels)

- 1D CNN layers:

- Kernel size 3–5

- Increasing filters (32 → 64 → 128)

- Captures local patterns (e.g., "scratching spikes" or "drinking rhythms")

- BiGRU layer (128 units):

- Learns past + future context

- Helps with distinguishing similar behaviors, especially transitions

- Dropout (0.3)

- Dense layer + Softmax

Architecture Block Diagram

IMU Window (150 × 6)

↓

Conv1D → ReLU

↓

Conv1D → ReLU

↓

BiGRU

↓

Dense Layer

↓

Softmax Output

This hybrid architecture performed better than:

- pure CNN

- pure GRU/LSTM

- simple statistical features + XGBoost

- handcrafted frequency features

Why CNN + BiGRU Works Better Than Other Approaches

Dog motion is messy, multi-scale, and highly non-periodic. A single modeling approach-pure CNN or pure RNN-fails to capture the complete picture. Our best results came from combining them.

1. Why CNNs Shine for IMU Data

CNNs are excellent at capturing local motion signatures. Many dog behaviors have distinctive micro-patterns:

- Scratching produces sharp, high-frequency spikes.

- Drinking generates rhythmic, low-amplitude oscillations.

- Shaking has explosive, dense energy bursts.

A 1D CNN with small kernels (3–5 samples) acts like a sliding feature extractor, detecting:

- sudden jerks

- periodic bursts

- frequency changes

- asymmetries between axes

These are patterns that classical statistical features or RNN-only approaches miss.

2. Why BiGRU Helps on Top of CNN

Once the CNN extracts local features, we still need temporal understanding over the full 1.5-second window. This is where BiGRU excels:

- It reads the sequence forward and backward, capturing full context.

- It understands transitions-walk → run, sit → lie down.

- It smooths out noisy CNN detections by seeing the broader structure.

Dog behaviors often have ambiguous local segments. A dog starting to run may produce signals similar to a strong walk cycle. BiGRU uses surrounding frames to disambiguate.

3. Why Pure CNN Fails

Without temporal aggregation:

- It treats every segment independently.

- It cannot understand pacing or duration.

- Mixed-behavior windows confuse it easily.

4. Why Pure GRU/LSTM Fails

RNN-only models struggle because:

- They lack strong local pattern detectors.

- Raw IMU data is too noisy without convolutional preprocessing.

- They incorrectly smooth out short micro-events (scratching, shaking).

5. Why This Hybrid Architecture Matches Dog Movement

Dog behaviors exist at multiple temporal scales:

- micro-patterns: 20–80 ms (scratching bursts)

- meso-patterns: 200–800 ms (drinking cycles)

- macro-patterns: 1–2 seconds (walk/run gait)

CNN extracts micro + meso patterns, BiGRU stitches them into a coherent macro interpretation.

Why This Matters for Pet Health - Confusion Matrix

Image Prompt: A confusion matrix heatmap for 6–8 classes, with darker cells along the diagonal. Clean, grid-based, readable at small sizes.

Model Performance (General Overview)

Instead of focusing on exact numbers, it’s more important to highlight how the model behaves across different dog actions.

Overall, the hybrid CNN + BiGRU architecture consistently demonstrates strong and reliable behavior separation across a wide variety of dogs, neck-band orientations, and activity intensities.

Behaviors the model understands very well

- Shaking – extremely distinctive, high-energy pattern

- Scratching – clear asymmetric bursts

- Running – stable rhythmic stride cycles

These behaviors produce motion signatures that are easy for the CNN to extract and for the BiGRU to contextualize.

Behaviors that benefit from more context

- Walking vs slow running – similar stride frequencies

- Eating vs drinking – subtle low-amplitude differences

- Posture transitions (sit → lie) – gradual, less structured signals

The model handles these reasonably well, but they inherently require more nuance due to overlapping motion characteristics.

Overall takeaway

The system delivers consistently dependable behavior classification for real-world use, especially as part of a multi-sensor pipeline at Hoomanely. Future iterations, combined with audio, proximity, and weight data, will push this even further.

Why This Matters for Pet Health

Lessons Learned & Engineering Insights

1. IMU orientation drift is a major pain

Axis rotation corrupts fixed-axis assumptions. Augmentation and normalization helped, but a future upgrade may require:

- Attitude estimation

- Quaternion-based representation

- Gravity-compensated signals

2. Some behaviors need multi-sensor context

Eating vs drinking often requires:

- Bowl-level audio

- Proximity data

- Weight change

IMU alone can’t always differentiate.

3. Sliding window size matters

A 1–2 sec window works best. Too short: no context. Too long: mixed behaviors.

4. Behavior boundaries are fuzzy

Dogs don’t "start walking" the way humans do-they transition gradually. This creates naturally noisy labels.

5. The model needs per-dog fine-tuning

Just like human gait varies by height and physique, dog motion varies by:

- Breed

- Age

- Neck girth

- Coat fluffiness

- Temperament

Future work includes lightweight on-device personalization layers.