The Anatomy of vBus: Understanding Connector Pin Blocks

Introduction: Organization is Everything

In our previous articles, we introduced the vBus ecosystem and explored the various SoM architectures at Hoomanely. We've talked about 100-pin CPU SoMs, 30-pin Power SoMs, and the challenges of standardization. But here's a question we haven't fully answered: what exactly lives on those pins?

A connector with 40, 50, or 100 pins can quickly become overwhelming chaos without a clear organizational strategy. Imagine debugging a system where power, data, control, and programming signals are randomly scattered across the connector—it would be a nightmare. This is why we've adopted a rigorous pin-block architecture for vBus.

Think of it like organizing a toolbox. You don't just throw everything in randomly. You create compartments: one for screwdrivers, one for wrenches, one for measuring tools. Each has its place, and you always know where to find what you need. The vBus connector follows the same philosophy.

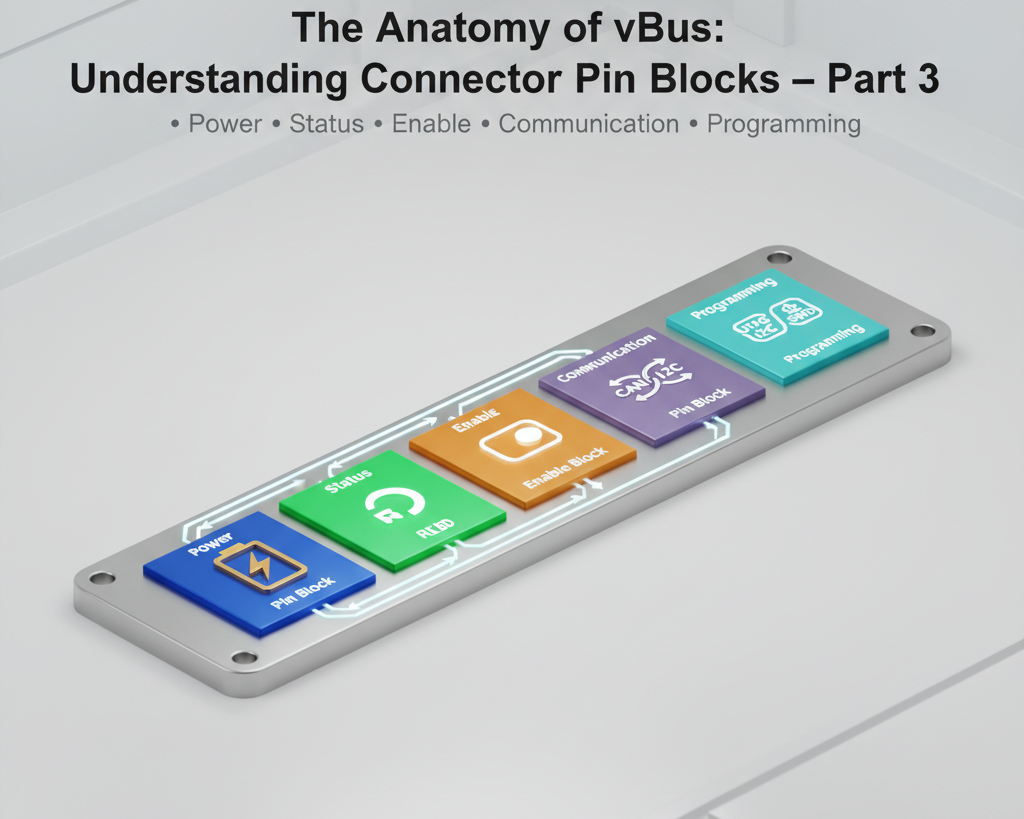

Today, we're diving deep into the five fundamental pin blocks that form the foundation of every vBus connector: Power, Status, Enable, Communication, and Programming. Understanding these blocks is key to both designing new SoMs and troubleshooting existing systems.

Power Block: The Foundation

Let's start with the most fundamental requirement of any electronic system: power. The Power Block is intentionally kept simple and pure—it delivers electrical energy, period. No control signals, no mixed functions, just clean power delivery.

The Voltage Rails

Our standard Power Block includes three primary voltage levels, chosen based on extensive analysis of common embedded system requirements:

5V Rail: This is the workhorse voltage for many peripherals, sensors, and legacy components. USB-powered devices, many motor drivers, and older sensor modules operate at 5V. We typically allocate multiple pins for this rail (2-4 pins depending on connector size) to handle currents ranging from a few hundred milliamps to several amps. The parallel pin configuration reduces resistance and distributes thermal stress.

3.3V Rail: The de facto standard for modern digital logic, microcontrollers, and many communication interfaces. I2C, SPI, UART—most operate at 3.3V logic levels. This rail powers the majority of digital components on our SoMs, including MCUs, communication transceivers, and many modern sensors. Like the 5V rail, we allocate multiple pins to ensure adequate current capacity and voltage stability.

1.8V Rail: The specialized voltage level for high-performance processors, certain high-speed interfaces, and modern low-power components. Many ARM Cortex-A series processors require 1.8V (or even lower) for their core voltage. MIPI interfaces, DDR memory, and advanced sensor technologies often operate at this voltage. While typically drawing less current than 3.3V or 5V rails, this voltage is critical for system stability.

Ground: The Unsung Hero

Here's something that novice engineers often overlook: ground pins are just as important as power pins—arguably more so. A poor ground connection can cause:

- Voltage offsets between modules leading to communication errors

- Ground bounce during high-speed switching, corrupting data signals

- EMI and noise coupling between systems

- Measurement errors in analog circuits

We allocate a generous number of ground pins in the Power Block—often equaling or exceeding the number of positive voltage pins combined. These aren't just electrical returns; they're the reference plane for the entire system. In high-speed designs, we strategically place ground pins adjacent to differential signal pairs to provide clean return paths and reduce crosstalk.

What's NOT in the Power Block

Notice what we deliberately exclude: power-good signals, enable controls, voltage monitoring, or any form of feedback. Those belong in other blocks. This separation serves multiple purposes:

- Clarity: Anyone looking at the schematic immediately knows the Power Block contains only passive power delivery

- Isolation: Keeping noisy switching signals away from the actual power delivery paths reduces interference

- Modularity: The same power pin assignments work across different SoM types regardless of their control architecture

The Power Block is designed to be the most stable, most reliable, most boring part of the connector. And that's exactly what we want.

Status Block: Visual Intelligence

If the Power Block is the foundation, the Status Block is the window into the system's soul. In complex modular systems, understanding what each module is doing at a glance is invaluable—especially during development and debugging.

The RGB LED Approach

Our Status Block uses a deceptively simple but powerful concept: a single RGB LED per SoM, specifically the WS2812 or similar addressable LED. Why this choice?

Single-Wire Control: WS2812 LEDs use a serial protocol that requires only one GPIO pin from the controlling MCU or CPU. This is pin-efficient—critical when every connector pin is precious real estate.

Full Color Spectrum: With independent red, green, and blue channels, you can create millions of colors. This means you can encode complex state information in visual form.

Chainable: Multiple WS2812 LEDs can be daisy-chained on the same data line, allowing a single controller to manage status LEDs across multiple modules.

Status Encoding Strategy

The real power comes from how we map system states to colors. Here's our standard encoding (though applications can customize):

Solid Green: Normal operation, everything is functioning correctly

Solid Blue: Programming/update mode, SoM is being flashed with new firmware Solid Yellow/Amber: Warning state, SoM is operational but something needs attention (low memory, sensor calibration needed, etc.)

Solid Red: Error state, SoM has encountered a critical issue

Pulsing Green: Initialization in progress, SoM is booting up

Pulsing Blue: Communication active, data is being transmitted/received Flashing Red: Critical fault requiring immediate attention

Magenta/Purple: Debug mode active

White: Factory test mode

Off: Powered down or sleep mode

Beyond Basic States

But it gets better. By varying brightness, pulse patterns, and color transitions, you can encode even more information:

- Pulse frequency can indicate data throughput (faster pulse = more activity)

- Color cycling can show progress through a multi-step process

- Brief color flashes can acknowledge commands or events

- Alternating colors can indicate conflict or resource contention

Imagine debugging a system with five SoMs. At a glance, you see: CPU SoM pulsing green (running normally), Power SoM solid green (stable), two Peripheral SoMs with pulsing blue (streaming sensor data), and one Communication SoM flashing yellow-blue (attempting to connect to network). You instantly understand the system state without connecting a debugger or reading logs.

The Multiplier Effect

Here's where it gets really interesting for multi-SoM systems. The CPU SoM can orchestrate synchronized LED patterns across all modules. A successful cloud upload might trigger a brief green wave cascading across all SoMs. A system fault could cause all LEDs to flash red in unison. This transforms individual status indicators into a coherent system-level display.

The Status Block typically occupies just 1-2 pins (one for the WS2812 data line, potentially one for power if not using the main 5V rail), but the information density it provides is remarkable.

Enable Block: Intelligent Power Management

The Enable Block introduces a critical capability: selective module control. In traditional embedded systems, everything powers up together and runs continuously. But modern applications demand more sophistication—the ability to dynamically enable, disable, or reset individual modules for power management, fault isolation, and system optimization.

Individual SoM Control

Each Peripheral SoM and subordinate module has a dedicated enable signal controlled by the CPU SoM (or main controller). This isn't just a nice-to-have feature; it's fundamental to robust system design:

Power Optimization: In battery-powered applications, you don't always need every sensor active. A GPS module might only need to run periodically. A camera might stay off until motion is detected. By selectively enabling modules, you can dramatically extend battery life. We've seen systems reduce average power consumption by 40-60% through intelligent enable management.

Fault Isolation: Suppose a Peripheral SoM develops a problem—perhaps a sensor enters a fault state and starts drawing excessive current or flooding the communication bus with garbage data. The CPU SoM can detect this (through current monitoring, communication timeouts, or watchdog failures) and disable the offending module without affecting the rest of the system. The system remains operational in a degraded but functional state.

Hot-Swap and Reset: The Enable Block allows for controlled module initialization. When a new SoM is connected or needs to be reset, the CPU can:

- Disable the module

- Stabilize power and communication bus

- Re-enable the module with proper timing

- Initialize and configure the newly started module

This is especially important for modules with complex startup sequences or those that need to be reset as part of error recovery procedures.

Implementation Details

The Enable Block typically consists of dedicated enable pins, one per controllable module. These are active-high or active-low signals (we standardize on active-high for consistency) that gate the power regulators or reset circuits on the target SoM.

On the hardware side, a simple implementation uses a load switch or MOSFET controlled by the enable signal to switch power to the downstream module. More sophisticated designs incorporate soft-start circuits to prevent inrush current spikes, or smart power management ICs that provide current limiting and fault reporting.

Sequencing and Dependencies

In complex systems, modules may have power-up dependencies. For example:

- The Power SoM must be stable before enabling any other modules

- The CPU SoM must boot before enabling Peripheral SoMs

- Certain sensors might require a specific warm-up sequence

The Enable Block, combined with software control, allows for sophisticated sequencing. The CPU SoM's boot firmware can bring up modules in the correct order, with appropriate delays between stages.

Watchdog Integration

Many of our SoMs include watchdog circuits that monitor the enable line. If the CPU SoM becomes unresponsive (locked up, crashed, etc.) and stops toggling watchdog signals, a hardware watchdog can pull the enable lines low, forcing a system-wide reset. This provides a failsafe recovery mechanism even when the software has completely failed.

Communication Block: The Data Highway

Now we arrive at the heart of vBus—the Communication Block. This is where data actually flows between modules, where sensor readings are transferred, where commands are sent, and where the system truly becomes a connected ecosystem rather than isolated components.

FDCAN: The High-Speed Backbone

At the core of our Communication Block is FDCAN (CAN FD), the flexible data-rate version of the Controller Area Network protocol. This might seem like an unconventional choice compared to USB or Ethernet, but there are excellent reasons:

Robustness: CAN was designed for harsh automotive and industrial environments. It features extensive error detection (15-bit CRC, stuff bit monitoring, frame checks), automatic retransmission, and fault confinement. A corrupted message is detected and retransmitted automatically without software intervention.

Multi-Master Architecture: Unlike SPI (master-slave) or UART (point-to-point), CAN is inherently multi-master. Any node can initiate communication without complex arbitration logic. This is perfect for our modular ecosystem where multiple SoMs might need to broadcast data simultaneously.

Priority-Based Arbitration: CAN uses non-destructive bitwise arbitration. Higher-priority messages automatically win bus access without collisions or delays. Critical sensor data or real-time control signals can have guaranteed low latency.

Speed: Traditional CAN runs at up to 1 Mbps, but CAN FD allows data rates up to 8 Mbps in the data phase. For many sensor applications, this is more than adequate, and it's achieved with simple twisted-pair wiring.

Distance and Reliability: CAN maintains signal integrity over several meters of cable, far better than high-speed serial protocols that require careful impedance matching and short traces.

We allocate two pins for FDCAN in the Communication Block: CANH and CANL (the differential pair). Optional: a third pin for CAN termination control in systems where dynamic termination is needed.

I2C: The Configuration Channel

Alongside FDCAN, we include a dedicated I2C interface (two pins: SDA and SCL). While FDCAN handles bulk data transfer, I2C serves a different purpose:

Module Identification: Each SoM contains an I2C EEPROM or MCU with a unique address storing module information—type, capabilities, serial number, calibration data, firmware version. When a SoM is connected, the CPU can enumerate it via I2C, similar to USB device enumeration.

Configuration and Control: Many sensors and peripherals have I2C-based configuration registers. Rather than creating custom configuration protocols over FDCAN, we use the standard I2C mechanism that most components already support.

Low-Speed Communication: For infrequent, low-bandwidth transactions (reading module temperature, setting LED brightness, updating configuration flags), I2C is simpler and more power-efficient than spinning up FDCAN messages.

Multi-Drop Simplified: I2C natively supports up to 127 devices on the same bus with addressing built into the protocol. Perfect for systems with many simple modules.

Interrupt Pin: Breaking the Polling Cycle

The third element of the Communication Block is an interrupt pin (or potentially multiple interrupt pins depending on connector size). Here's why this matters:

Polling is inefficient. If the CPU SoM has to constantly ask each Peripheral SoM "do you have data for me?" that wastes processor cycles and power. Instead, Peripheral SoMs can assert an interrupt line when they have important data or events to report.

This enables event-driven architectures:

- A motion sensor triggers an interrupt when it detects movement

- A communication module interrupts when data arrives from the network

- A fault condition immediately signals the CPU

The interrupt pin is typically open-drain or open-collector, allowing multiple modules to share the same line (wired-OR configuration). The CPU services the interrupt and queries modules via I2C to determine which one triggered it.

Communication Block Pin Count

In summary, the Communication Block typically occupies:

- 2 pins for FDCAN (CAN_H, CAN_L)

- 2 pins for I2C (SDA, SCL)

- 1-2 pins for interrupts (INT, optional INT2)

That's 5-6 pins total delivering multiple communication protocols with different characteristics optimized for different use cases. It's an elegant solution to the multi-protocol challenge.

Programming Block: Bringing Systems to Life

The final piece of the vBus connector puzzle is the Programming Block—the most developer-centric section of our pinout. This block is all about one critical phase in a module's lifecycle: getting firmware onto it and debugging when things go wrong.

JTAG/SWD: The Low-Level Interface

Every microcontroller and processor needs a way to be programmed and debugged. For ARM-based systems (which comprise the majority of our SoMs), that means SWD (Serial Wire Debug) or JTAG (Joint Test Action Group).

SWD is our preferred protocol for MCU-based modules. It requires just two signals:

- SWDIO (data)

- SWCLK (clock)

With these two pins, you get:

- Flash programming

- Real-time debugging (breakpoints, single-stepping, variable inspection)

- Memory access for diagnostic dumps

- CPU core register reading

For more complex CPU SoMs, particularly those running Linux, we sometimes include full JTAG (5 pins: TDI, TDO, TMS, TCK, TRST). JTAG provides additional capabilities like boundary scan testing and multi-core debugging.

Boot Pins: The Power-On Selector

ARM microcontrollers and many embedded processors have boot mode pins that determine where the processor looks for code at power-up:

- Boot from internal flash (normal operation)

- Boot from external memory

- Enter bootloader mode for USB or UART programming

- Enter DFU (Device Firmware Update) mode

These pins are sampled during reset. By controlling their state through the vBus Programming Block, we can remotely force a module into programming mode without physical button presses. This is invaluable for:

- Field updates: Updating firmware on deployed systems without disassembly

- Manufacturing: Programming modules in a production fixture

- Recovery: Forcing a boot mode when flash memory is corrupted

The Programming Block typically includes 1-3 boot pins, depending on the processor's requirements. Some ARM processors use a single BOOT0 pin, others use multiple pins for different boot modes.

UART: The Universal Debug Port

While SWD/JTAG are powerful, they require specialized hardware tools (like ST-Link, J-Link, or similar debuggers). For quick testing, logging, and basic interaction, nothing beats a good old UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver-Transmitter).

The Programming Block includes a UART interface (TX and RX pins) that serves multiple purposes:

Console Output: Most embedded operating systems and firmware provide a debug console over UART. System boot messages, kernel logs, application debug prints—all accessible through a simple serial terminal.

Bootloader Communication: Many MCUs have built-in UART bootloaders. By entering bootloader mode (via boot pins) and sending the firmware over UART, you can program a module without specialized debug hardware.

Interactive Debug: During development, a UART command-line interface allows developers to poke registers, trigger functions, or query system state interactively.

Production Testing: In manufacturing, automated test equipment can communicate with modules via UART to run diagnostics and functional tests.

USB: The Modern Alternative

Some of our more advanced SoMs include USB in the Programming Block (D+ and D- signals, plus power if needed). USB serves similar purposes as UART but with significant advantages:

- Much higher data rates (12 Mbps for USB 2.0 Full Speed vs. typical 115200 bps for UART)

- Native support in most operating systems without drivers

- Ability to emulate multiple devices (mass storage, CDC serial, HID) over one connection

- Power delivery for self-powered programming (no external supply needed during development)

For example, a USB-programmable module might appear as:

- A virtual serial port for debug console

- A mass storage device where you can drag-and-drop firmware files

- A DFU device for standardized firmware updates

Independent Programmability: The Key Advantage

Here's where the Programming Block's inclusion in vBus really shines: every SoM can be independently programmed and debugged. You don't need to disassemble the system or disconnect modules. A debugging probe attached to the vBus connector can access any module's Programming Block.

During development, this means:

- An engineer can debug a Peripheral SoM's firmware while the CPU SoM continues running

- Multiple engineers can work on different modules simultaneously without interference

- Firmware updates can be deployed to specific modules without disrupting others

In production, this enables:

- End-of-line programming where all modules are programmed in-system after assembly

- Selective firmware updates in the field (update only the modules that need it)

- Diagnostic access to any module for troubleshooting

Programming Block Pin Budget

The Programming Block typically occupies:

- 2-5 pins for JTAG/SWD (depending on protocol choice)

- 1-3 pins for boot mode control

- 2 pins for UART (TX, RX)

- Optional: 2 pins for USB (D+, D-)

That's 5-12 pins depending on the SoM's complexity and requirements—a significant allocation, but absolutely justified by the development velocity and maintainability it enables.

Bringing It All Together: The Complete Pinout

Let's step back and look at how these five blocks combine into a complete vBus connector:

For a 40-pin Peripheral SoM:

- Power Block: 10 pins (5V ×2, 3.3V ×2, 1.8V ×1, GND ×5)

- Status Block: 1 pin (WS2812 data)

- Enable Block: 1 pin (enable input)

- Communication Block: 6 pins (FDCAN ×2, I2C ×2, INT ×2)

- Programming Block: 8 pins (SWD ×2, BOOT ×1, UART ×2, USB ×2)

- Reserved/Special: 14 pins (analog, GPIO, expansion)

For a 100-pin CPU SoM: The same block structure scales up with more communication channels, more power pins for higher current, additional programming interfaces, and significantly more expansion pins for application-specific signals.

This hierarchical, block-based organization brings multiple benefits:

Consistency: An engineer familiar with one vBus SoM can immediately understand another. The power pins are always in the same relative position, programming is always in its designated block, etc.

Debugging Efficiency: When troubleshooting, you know exactly where to probe. Communication issue? Check the Communication Block. Programming failure? Go straight to the Programming Block.

Design Reuse: Carrier boards can use similar routing strategies for the blocks across different SoM types, reducing design time and improving signal integrity through proven patterns.

Documentation Simplification: Rather than documenting 100 individual pins, we document five conceptual blocks. It's easier to learn, easier to teach, and easier to maintain.

Conclusion: Architecture in the Details

The vBus pin-block architecture might seem like a small detail in the grand scheme of modular embedded systems. But as we've seen, it's these details—the careful organization of power, status, control, communication, and programming—that transform a random collection of pins into a coherent, usable, maintainable system.

By rigidly defining these five blocks and their purposes, we've created a language that our engineers, our manufacturing partners, and our customers can all speak fluently. Whether you're bringing up a new SoM, debugging a field issue, or designing the next generation of products, the block structure provides guardrails that guide you toward success.

In many ways, this is the essence of good systems engineering: taking complexity and organizing it into comprehensible, manageable chunks. The vBus connector blocks are our way of saying "here's how we think about connectivity." And when everyone thinks about it the same way, collaboration becomes effortless and innovation accelerates.