Training Production Models Without the Luxury of Big Data

"We need at least a million labeled images to train this model."

If you've ever heard this from a data scientist and felt your heart sink, you're not alone. The reality of building production ML systems is that you rarely have the luxury of massive, perfectly labeled datasets. Budget constraints, time pressure, privacy concerns, or simply the nature of your problem—there are countless reasons why you might be staring at a few hundred samples wondering how to build something that actually works.

The good news? Modern machine learning has evolved far beyond the "more data solves everything" paradigm. Today, we have a sophisticated toolkit of techniques that can help you build robust models even when your dataset is small.

This is a practical exploration of how to tackle the small data problem—not from a theoretical perspective, but from the trenches of real-world ML deployment.

Why Small Data is the Real-World Default

Before diving into solutions, let's acknowledge why this problem is so pervasive.

In academic papers and tech company blog posts, you'll read about models trained on millions of images or massive text corpora. But most real-world ML problems look nothing like this. You're building a defect detection system for a manufacturing line that's only been running for three months. You're classifying rare medical conditions where only a few hundred cases exist globally. You're detecting specific behaviors in video where labeling is expensive and time-consuming.

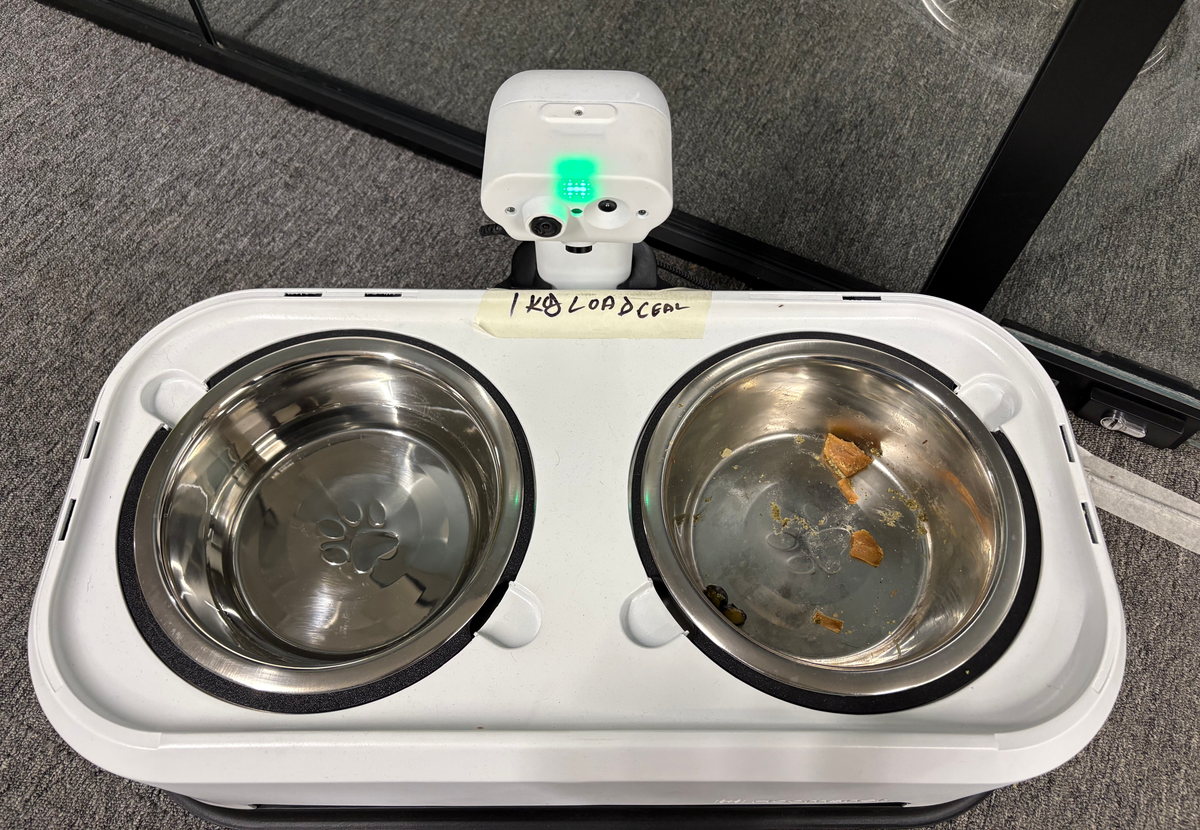

At Hoomanely, we face this constantly. We're building preventive pet healthcare technology through our smart feeding bowl, Everbowl. Training a model to detect subtle changes in a specific breed's eating behavior? We might only have data from dozens of pets of that breed. Identifying early signs of a rare health condition? Even rarer. The promise of AI-powered health insights means nothing if we can't build reliable models from the limited data real pet parents generate.

The challenge isn't just technical—it's economic. Labeling data is expensive. Collecting edge cases takes time. And in fast-moving product development, you often need a working model yesterday, not after six months of data collection.

The Solution Space: Techniques for Small Data Success

When faced with limited training data, several approaches can help you build models that generalize well. Let's explore each one and understand when and how to apply them.

Transfer Learning: Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

The single most impactful technique for small data problems is transfer learning—taking a model trained on a large dataset and adapting it to your specific task.

The intuition is elegant: a model trained to recognize millions of everyday objects has already learned fundamental concepts like edges, textures, shapes, and object parts. These low-level and mid-level features are surprisingly universal. A model that learned to detect cat ears in photos can probably help you detect dog ears too. A model trained on general images understands lighting and perspective in ways that transfer to your specific domain.

How it works in practice: You take a pretrained model, freeze most of its layers, and only retrain the final layers on your small dataset. The frozen layers act as a sophisticated feature extractor, while the final layers learn your specific task.

For image tasks, models pretrained on large public datasets are remarkably effective starting points. If you're building a pet breed classifier with only a small number of images per breed, starting from pretrained weights can give you dramatically better results than training from scratch.

The key decisions are how many layers to freeze and how aggressively to fine-tune. With very small datasets (hundreds of samples), freeze everything except the final classification layer. With slightly larger datasets (thousands), you can progressively unfreeze and fine-tune deeper layers using a lower learning rate—a technique called gradual unfreezing.

This approach doesn't require any additional data collection. You're simply leveraging the knowledge encoded in models that others have trained, adapting it to your specific problem. It's the closest thing to a free lunch in machine learning.

Knowledge Distillation: Learning from a Teacher

Sometimes you have access to a large, powerful model but need to deploy something smaller and faster. Or you've managed to train a decent model but want to improve a smaller version for edge deployment. This is where knowledge distillation comes in.

Knowledge distillation treats a large, accurate model (the "teacher") as a source of training signal for a smaller model (the "student"). Instead of learning from hard labels alone, the student learns from the teacher's soft predictions—the full probability distribution over classes.

Why does this help with small data? Because the teacher's predictions contain more information than binary labels. When a teacher model outputs probability distributions across multiple classes, it's teaching the student about the relationships and similarities between categories. This richer signal helps the student generalize better from limited examples.

In practice, you train the student on a combination of two losses: the standard loss against true labels, and a distillation loss that encourages the student to match the teacher's output distributions. A temperature parameter controls how "soft" these distributions are—higher temperatures reveal more about the teacher's uncertainty and between-class relationships.

Knowledge distillation is particularly powerful when combined with unlabeled data. Your teacher can generate pseudo-labels for unlabeled samples, effectively expanding your training set. This semi-supervised approach can dramatically improve student model performance when labeled data is scarce.

For deployment on edge devices like our Everbowl, this technique lets us maintain high accuracy while keeping models lightweight enough to run efficiently on embedded hardware.

Data Augmentation: Making More from Less

If you can't collect more data, the next best thing is to artificially expand what you have through augmentation—applying transformations that preserve the label while creating variations your model hasn't seen.

Classical augmentation for images includes rotations, flips, crops, color jittering, and brightness adjustments. These are computationally cheap and surprisingly effective. For pet monitoring applications, horizontal flips make sense (a dog eating from the left looks similar to one from the right), but vertical flips don't (upside-down pets are rare). Domain knowledge guides which augmentations are reasonable.

Modern techniques get more sophisticated. MixUp blends pairs of images and their labels, creating synthetic training examples that live "between" classes. Counterintuitively, this improves generalization by forcing models to learn more robust features. CutMix pastes patches from one image onto another, forcing the model to recognize objects from partial views—exactly what happens in real-world occlusions.

There are also learned augmentation strategies that automatically search for or randomly select augmentation policies during training, effectively discovering the most beneficial transformations for your specific dataset.

For time-series data like sensor readings from weight sensors or feeding patterns, augmentation looks different: time warping, magnitude scaling, adding synthetic noise, or window slicing can all create realistic variations from limited samples.

The key principle: augment conservatively at first, then expand based on validation performance. Overly aggressive augmentation can hurt more than it helps by creating unrealistic samples that confuse your model. Always validate that your augmentations make sense in your problem domain.

Synthetic Data Generation: Creating What You Need

What if you could generate training data from scratch? Recent advances in generative models make this increasingly viable, though with important caveats.

Generative models can create synthetic images that look remarkably realistic. If you're building a classifier and only have limited images of certain classes, a well-trained generative model could create more synthetic examples to balance your dataset.

The challenge is that generating high-quality, diverse synthetic data often requires substantial data itself—somewhat defeating the purpose. However, you can often use a generative model trained on a related, data-rich domain and adapt it to your specific needs through techniques like few-shot generation or conditional synthesis.

Simulation is another form of synthetic data that's particularly relevant for certain domains. If you're training models for robotics, 3D scenes, or physical interactions, high-fidelity simulators can generate unlimited training samples with perfect labels. The simulation-to-reality gap remains a challenge, but techniques like domain randomization help bridge it by varying simulation parameters to create diverse training conditions.

For our bowl detection system at Hoomanely, we could theoretically generate thousands of synthetic bowl images with different lighting conditions, angles, and contents. However, we've found that real-world data, even if limited, is often more valuable than large amounts of purely synthetic data. Synthetic data works best as a supplement, not a replacement.

Active Learning: Choosing What to Label

When labeling data is expensive, wouldn't it be nice if your model could tell you which samples are most valuable to label next? That's active learning.

The core idea: instead of randomly labeling your dataset, use your current model to identify samples where it's most uncertain or where labeling would provide maximum information. Label those samples, retrain, and repeat. This iterative process can dramatically reduce labeling requirements while achieving strong performance.

Uncertainty sampling queries samples where the model's predictions are least confident—these are near decision boundaries where labels provide maximum information. Query-by-committee uses multiple models and selects samples where they disagree most. Expected model change selects samples that would cause the largest gradient updates if labeled.

Practically, this means: train an initial model on your small labeled set, apply it to your unlabeled pool, select the most informative samples based on your chosen strategy, label just those samples, retrain and repeat.

Active learning is particularly powerful when combined with transfer learning. Start with a pretrained model, fine-tune on your small initial dataset, then use active learning to intelligently expand it. The pretrained features help the model make better uncertainty estimates even with minimal data.

This approach is ideal when you have a large pool of unlabeled data but limited budget for labeling. Instead of paying to label thousands of random samples, you label only the few hundred that matter most—guided by the model itself.

Putting It All Together: A Practical Framework

These techniques aren't mutually exclusive—they're most powerful when combined thoughtfully.

Start with transfer learning. This gives you the biggest initial boost with the least effort. Choose a pretrained model from a related domain and fine-tune on your small dataset. This should always be your first step.

Apply smart augmentation. Expand your effective dataset size through domain-appropriate transformations. Start conservative, measure validation performance, then expand based on what works. Think carefully about which transformations make sense for your problem.

Consider distillation if deploying to constrained environments. Train your best possible teacher model using all available data and techniques, then distill to a smaller student for production. This lets you maintain accuracy while meeting deployment constraints.

Use active learning for strategic data collection. If you have budget for more labeling, let your model guide where that budget is spent. Don't label randomly—label intelligently.

Supplement with synthetic data cautiously. Generate additional training samples if you have access to good generative models or simulators, but always validate that synthetic data actually improves real-world performance. Measure carefully before relying on it.

At Hoomanely, this multi-pronged approach lets us build robust pet health monitoring systems without requiring millions of samples from each pet breed and condition. We start with models pretrained on general animal images, augment heavily with domain-appropriate transformations, and use active learning to efficiently label the edge cases that matter most for health detection.

Key Takeaways

Modern ML gives us powerful tools for the small data regime—you don't need millions of samples to build production systems.

Transfer learning should be your default starting point. Pretrained models encode enormous amounts of knowledge that transfers surprisingly well across domains. Almost every small data problem benefits from starting here.

Augmentation is cheap insurance. Thoughtful data augmentation can multiply your effective dataset size with minimal effort. The key is choosing augmentations that make sense for your domain.

Knowledge distillation helps you deploy efficient models while maintaining accuracy, especially when edge deployment or inference speed matters.

Active learning maximizes your labeling budget by intelligently choosing what to label next, not just randomly sampling your unlabeled pool.

Combine techniques strategically. The real art is knowing which methods to use together for your specific problem. Small data isn't a limitation—it's a constraint that forces you to be smarter about how you build models