Turning Ears into Eyes: Cleaning Audio Datasets Visually

Building high-quality audio datasets is a uniquely painful challenge. Unlike images, where you can glance at a grid of thumbnails and instantly spot a "bad" sample, audio requires time. You have to listen. Linear time is the enemy; you cannot "fast forward" through a dataset validation task without risking missing the very anomalies you are trying to catch.

At Hoomanely, where we build advanced AI for preventive pet healthcare, we deal with massive libraries of audio. From anomaly detection to identifying normal eating habits, our models rely on pristine data to differentiate subtle health markers from household noise. When you are scraping public audio or collecting real-world samples, the data is inevitably messy. We found ourselves facing a "Wall of Sound"—thousands of clips labeled as a specific health event that were actually just loud static, human speech, or silence.

Listening to them one by one was impossible. So we stopped listening. We started looking.

The Problem: The "Wall of Sound"

The standard pipeline for curating an audio dataset usually looks like this:

- Scrape/Record raw audio based on keywords.

- Split into short chunks.

- Manually Listen to verify.

Step 3 is the bottleneck. If you have thousands of ten-second clips, that’s dozens of hours of pure listening time—assuming you don't pause, rewind, or take a break. In reality, it’s weeks of work.

Worse, human fatigue is real. After listening to hundreds of identical-sounding clips, they all start to blur together. A labeler might accidentally approve a similar-sounding outlier (like a door squeak instead of a health sound) simply because their ears are tired. This introduces label noise, which caps the performance of any model you train downstream.

We needed a way to spot outliers without hitting "play."

The Approach: Don't Listen, Look

Our hypothesis was simple: If two sounds strictly sound different to a human, they should look different to a model.

We didn't invent this idea; embedding visualizations are a staple in machine learning. However, we took it a step further. We didn't just use visualization for analysis (i.e., "Oh look, a cluster"); we built a pipeline to use it for active curation and automatic cleaning.

The workflow relies on three core technologies:

- PANNs (Pre-trained Audio Neural Networks): Specifically the Cnn14 embedding model, which acts as our "ears."

- UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection): Which acts as our mapmaker, squashing high-dimensional "concepts" into 2D or 3D space.

- Linear SVM (Support Vector Machine): The "scalpel" we use to slice the data.

The Process: From Signal to Geometry

1. The Embedding Layer: Mapping Sound to Numbers

We processed every audio clip through the PANNs Cnn14 model. Using the layer before the final classification head gives us a 2048-dimensional vector for each sound. This vector captures the "texture" of the audio—pitch, timber, rhythm, frequency distribution—but ignores the raw waveform details.

At this stage, a "target sound" and a "background noise" might both be loud, but their 2048-dimensional fingerprints are vastly different.

2. The Projection Layer: Finding the Topology

2048 dimensions are impossible to visualize. We used UMAP to project these vectors down to just 2 dimensions (x, y).

This is where the magic happens. UMAP preserves local structure. This means if Clip A and Clip B are close to each other in the 2D plot, they are almost certainly semantically similar.

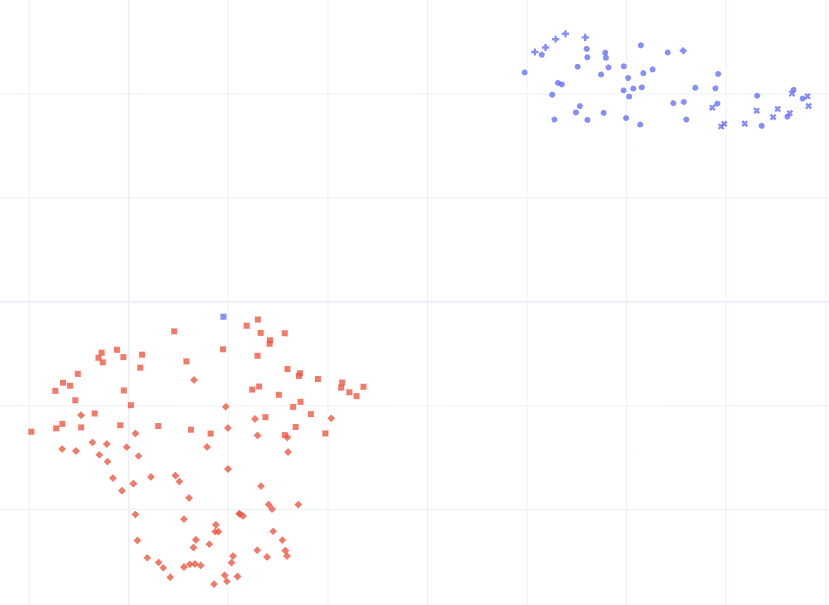

When we plotted our binary classification dataset, we didn't see a random cloud of points. We saw two distinct "continents." But importantly, we saw "islands" drifting off the coast.

- The Blue Continent (Class A): Tight, dense cluster.

- The Red Continent (Class B): More spread out (representing higher variance).

- The "Outliers": A smattering of dots far away from the main clusters. When we clicked on these dots (using interactive plots like Plotly), they weren't our target sounds at all. They were TV static, cars driving by, or corrupted audio.

We had successfully identified the "garbage" without listening to a single file.

3. The "Geometry Hack": SVM on UMAP

We could have manually drawn a circle around the good clusters, but we wanted an automated, reproducible approach.

We realized that while the original 2048 features were complex, the 2D UMAP projection was simple. The two classes were roughly linearly separable in this 2D space.

So, we trained a Linear SVM on the (x, y) UMAP coordinates—not the original audio embeddings.

# The Concept: Using geometry to clean data

svm = LinearSVC(class_weight='balanced')svm.fit(umap_2d_coords, labels)

# Get distance to the decision boundary

distances = svm.decision_function(umap_2d_coords)This gave us a decision boundary—a line drawn in the sand between the two classes. But more importantly, it gave us a distance metric:

- High positive distance: Confident Class A.

- High negative distance: Confident Class B.

- Near Zero: Ambiguous / Mixed.

We implemented a cleaning protocol based on this geometry:

- Remove Misclassified: If a file labeled "Class A" fell deep into the "Class B" territory on the map, it was almost always a labeling error. We deleted it.

- Remove Ambiguous: If a file fell within a generic

thresholddistance of the line, it meant the model wasn't sure. In preventive health, precision is better than recall. We'd rather toss a valid file than keep a confusing one. We deleted these too.

The Results: Purity by Default

By applying this visual and geometric filter, we reduced our dataset size significantly, but the quality skyrocketed.

When we re-ran the clustering on the cleaned dataset, the "islands" of noise were gone. The two continents were sharper and more distinct. We had effectively bootstrapped a high-quality dataset from scrapes without the massive overhead of manual validation.

This approach fits perfectly with the Clean Code / Clean Data philosophy. Instead of hoping our complex models would learn to "ignore" the noise, we used simpler, interpretable tools (UMAP + SVM) to remove the noise at the source.

Key Takeaways

- Visual > Auditory: For large datasets, your eyes are faster than your ears. Use dimensionality reduction to turn temporal data into spatial data.

- Embeddings are Searchable: Use pre-trained models (like PANNs or CLAP) as generic feature extractors. You don't need to train a model from scratch to find outliers.

- Geometry is a Filter: Don't be afraid to apply simple geometric rules (distances, clusters) to high-dimensional problems. Sometimes a simple line in 2D space is the most robust filter you can build.

- Iterate on Data, Not Models: Improving the dataset via cleaning often yields higher accuracy gains than tweaking the hyperparameters of the final model.