Two-Step Detection: Building Reliability Through Layered Computer Vision

The best engineering solutions aren't always the most complex ones. Sometimes, the smartest approach is knowing when to keep it simple—and when to add just enough redundancy to make it bulletproof.

At Hoomanely, we build preventive pet healthcare technology that helps pet parents stay ahead of health issues before they become serious. Our flagship product, Everbowl, is a smart feeding bowl equipped with weight sensors, cameras, and thermal sensors to track feeding patterns and vital pet health data. But even the most sophisticated hardware means nothing if the software can't reliably answer one fundamental question: which bowl contains what?

This is the story of how we solved that problem with a two-layer approach that's both elegantly simple and remarkably robust.

The Problem: When Left and Right Don't Matter

Everbowl has two bowls—one typically for food, one for water. Everything our system does afterward—tracking hydration levels, calculating calorie intake, detecting eating pattern changes—depends entirely on knowing which bowl holds which content.

The naive solution? Just tell users: "Put water on the left, food on the right." Problem solved, right?

Wrong.

In the real world, users don't follow instructions perfectly. Bowls get switched during cleaning. Pet parents might have their own organizational logic. Some might even experiment with different setups. We couldn't build our entire analytics pipeline on the assumption that users would always follow a rigid bowl placement rule.

We needed the system to be smart enough to figure it out automatically—and to do so reliably, every single time.

Exploring the Solution Space

When approaching bowl identification, we had several theoretical options:

Pure computer vision classification: Train a deep learning model to classify "food" vs "water" directly from camera images. Sounds sophisticated, but food varies wildly—kibble, wet food, raw diets, different colors, textures, and portions. This would require massive training datasets and constant retraining as users feed different foods.

Liquid detection algorithms: Use advanced CV techniques to detect water's surface properties—reflections, transparency patterns, surface tension markers. Technically possible, but computationally expensive and prone to failure with different lighting conditions, bowl materials, and water levels.

Sensor fusion approaches: Combine weight patterns over time (water decreases gradually, food in discrete eating events) with thermal signatures (water typically cooler). Accurate in theory, but requires extended observation periods. What about the first few minutes after setup?

Physical markers with simple detection: Place identifiable markers in the bowls and detect them using basic computer vision. Fast, computationally cheap, and deterministic—but potentially fragile if markers get obscured or lighting conditions vary.

Each approach had merit. But we weren't building a research project—we were building a product that needed to work in real homes, under real conditions, with real pet parents who just want their device to work.

Our Approach: Simplicity First, Redundancy Second

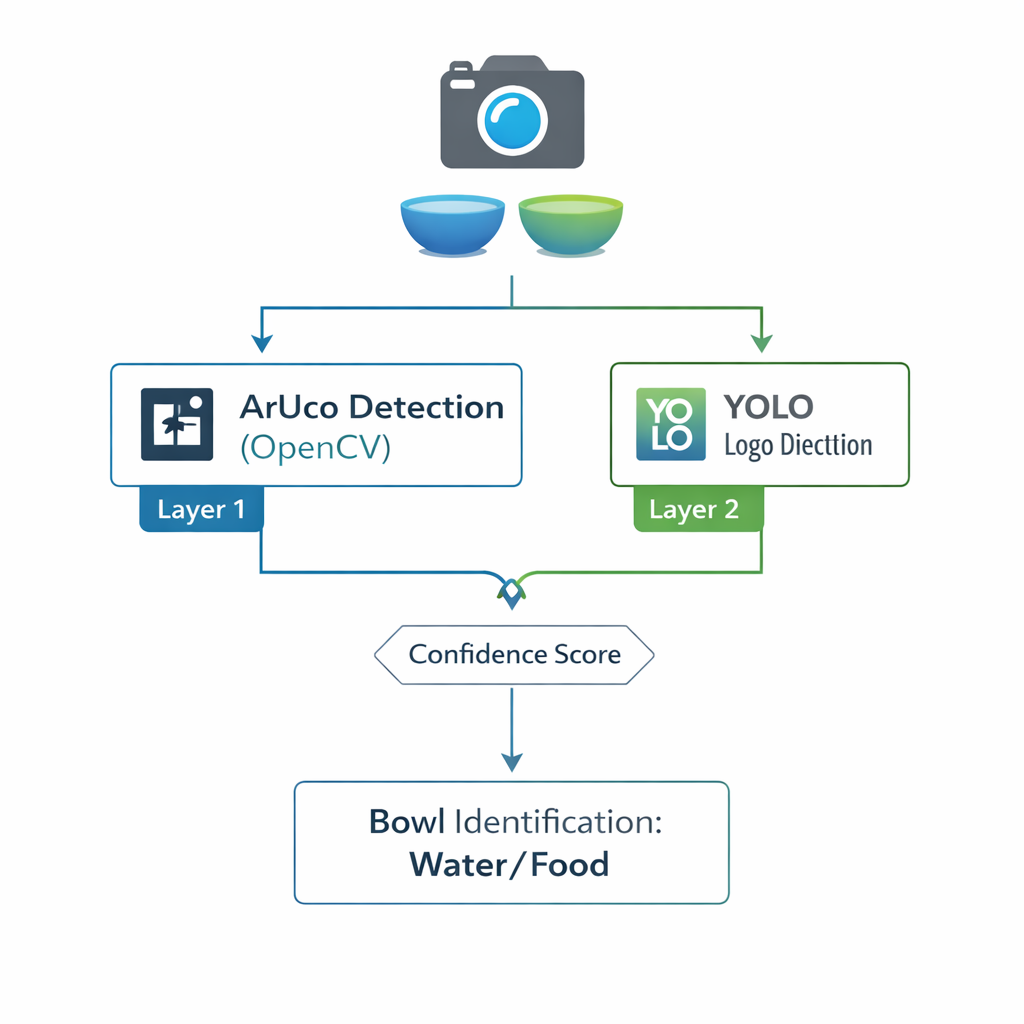

We chose to build a two-layer detection system, starting with the simplest possible approach and adding intelligent backup.

Layer 1: ArUco Marker Detection

ArUco markers are square fiducial markers originally developed for camera calibration and pose estimation. They're essentially QR-code-like patterns that OpenCV can detect incredibly efficiently. We printed ArUco markers on the bottom of each bowl.

The logic was beautifully straightforward: water is transparent. If the camera can see the ArUco marker through the bowl's contents, that bowl contains water. If the marker is obscured by opaque food, it's the food bowl.

This approach had several advantages:

- Lightning fast: OpenCV's ArUco detection runs in milliseconds, even on modest hardware

- Computationally cheap: No GPU required, no heavy neural networks

- Deterministic: When it works, it's 100% accurate

- No training required: No datasets to collect, no models to maintain

We implemented this using OpenCV's aruco module—a few dozen lines of code that could identify which bowl held water within frames of the camera feed becoming available.

Layer 2: YOLO-Based Logo Detection

But we're engineers. We know that "when it works" is doing a lot of heavy lifting in that sentence.

ArUco markers work by detecting edges and corners in specific geometric patterns. They're remarkably robust, but they have an Achilles heel: they need clean, unobstructed views of those edges. A bit of condensation on the bowl. A reflection from overhead lighting. A corner of the marker slightly folded during manufacturing. Any of these could cause detection failure.

We needed a backup system—but one that didn't require us to train a complex food-vs-water classifier. The solution came from a creative bit of product design: we printed Hoomanely's logo around each ArUco marker.

This served dual purposes:

- Brand presence: The bowls looked more polished and authentic with our logo

- Computer vision target: The logo gave us a secondary detection target

We trained a lightweight YOLOv8 detection model on our logo. YOLO (You Only Look Once) is designed for real-time object detection, and for a single, consistent logo design, it requires relatively little training data. We collected a few hundred images of our bowls under various lighting conditions, annotated the logos, and trained a compact model.

The logo detection didn't need to be perfect—it just needed to work when ArUco failed. Since logos are visually distinct from geometric patterns, they're more resilient to edge distortion and lighting variations that trip up ArUco detection.

The Implementation: Two Layers, One Reliable System

Our detection pipeline works like this:

1. Primary Detection (ArUco): Every frame, we run ArUco detection first. It's so fast that it adds negligible latency. If we successfully detect a marker in one bowl, we immediately know that's the water bowl.

2. Fallback Detection (YOLO): If ArUco detection fails or gives ambiguous results (detects in both bowls or neither), we invoke the YOLO model. This runs slightly slower but still completes in under 100ms on our hardware.

3. Confidence Scoring: Both systems provide confidence scores. We weighted ArUco detection higher when both systems agree, but trusted YOLO when ArUco failed entirely.

4. Temporal Consistency: We don't make decisions on single frames. We aggregate detections over 2–3 seconds of video, requiring consistent identification before committing to a bowl assignment.

This layered approach gave us the best of both worlds: the speed and simplicity of ArUco for 90% of cases, with YOLO-based redundancy catching the remaining 10% where lighting, condensation, or other factors interfered with marker detection.

Key Takeaways

1. Start simple, add complexity only when needed: ArUco markers solved 90% of our problem with 10% of the complexity. That's a trade-off worth making every time.

2. Redundancy beats perfection: Rather than trying to make ArUco detection perfect under all conditions, we accepted its limitations and added a complementary system with different failure modes.

3. Product design and engineering can work together: The logo around our markers wasn't just aesthetic—it was infrastructure. Good design enables good engineering.

4. Real-world conditions will humble you: What works perfectly in controlled testing can fail in unexpected ways when users introduce variability you never imagined.

5. Know when to stop: We could have added a third layer, or a fourth. We could have implemented sensor fusion with weight and thermal data. But two layers gave us 99%+ accuracy—chasing the last 1% would have been over-engineering, not product development.