When MelCNN Hallucinates: Why Clean Spectrograms Still Produce Wrong Sounds

How MelCNN learned “ghost sounds” from mislabeled silence

Introduction

Hallucination is usually discussed in the context of large language models—confident answers to questions that were never asked, or facts that never existed. But hallucination isn’t exclusive to text models. In audio systems, especially CNN‑based classifiers like MelCNN, hallucination shows up in a quieter, more dangerous form: high‑confidence predictions for sounds that never happened.

We ran into this exact failure mode while deploying MelCNN for indoor dog‑audio classification. The spectrograms looked clean. The pipeline was stable. Offline metrics were acceptable. And yet, in production, the model kept firing on silence, fans, distant traffic hum, and room reverberations—confidently labeling them as meaningful sound events.

Cover Image Prompt (Canva / Midjourney / DALL·E):

A clean mel spectrogram fading into abstract ghost‑like audio waves, minimalist technical illustration style, dark background, subtle glow, representing audio hallucination in machine learning

This post breaks down why MelCNN hallucinated, how mislabeled silence became “ghost sounds,” and what actually worked to fix it—beyond just adding more data.

The Problem: Clean Spectrograms, Wrong Sounds

At first glance, nothing looked wrong:

- Audio was preprocessed correctly

- Mel spectrograms were normalized

- Training loss converged smoothly

- Validation accuracy looked fine

But when we inspected false positives, a pattern emerged:

Most hallucinations happened on low‑information audio—near silence, steady background noise, or transitional frames with faint energy.

The model wasn’t confused.

It was overconfident.

The core issue

MelCNN wasn’t hallucinating randomly. It was responding to learned correlations that shouldn’t have existed.

And those correlations came from the dataset.

How Silence Became a Class (Accidentally)

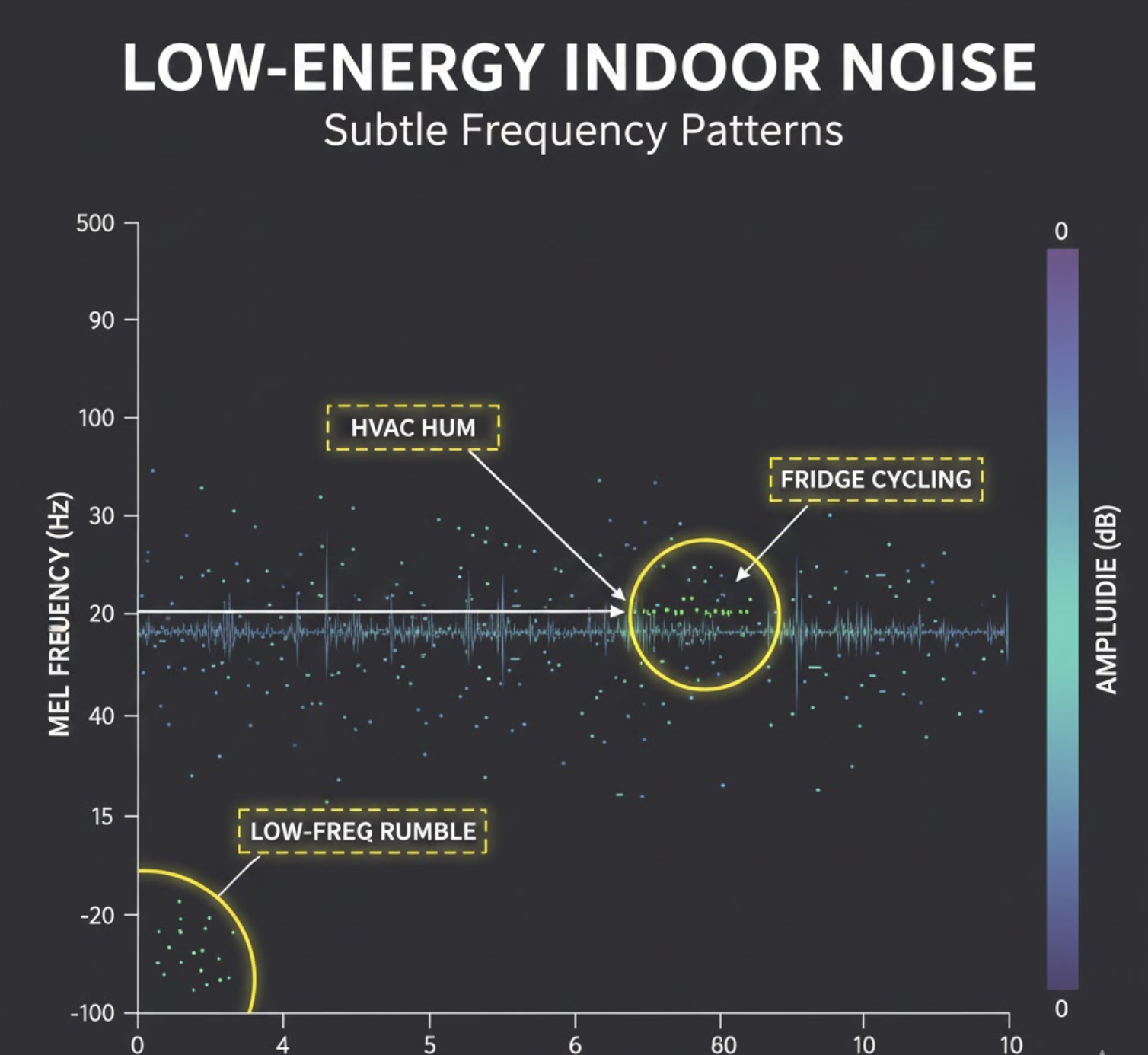

1. Mislabeled negatives were not truly negative

Our “negative” samples often included:

- Truncated clips with leading or trailing silence

- Indoor ambient noise recorded during real events

- Low‑energy audio mistakenly labeled as positives

To a human listener, these sounded like nothing.

To a CNN, they had structure.

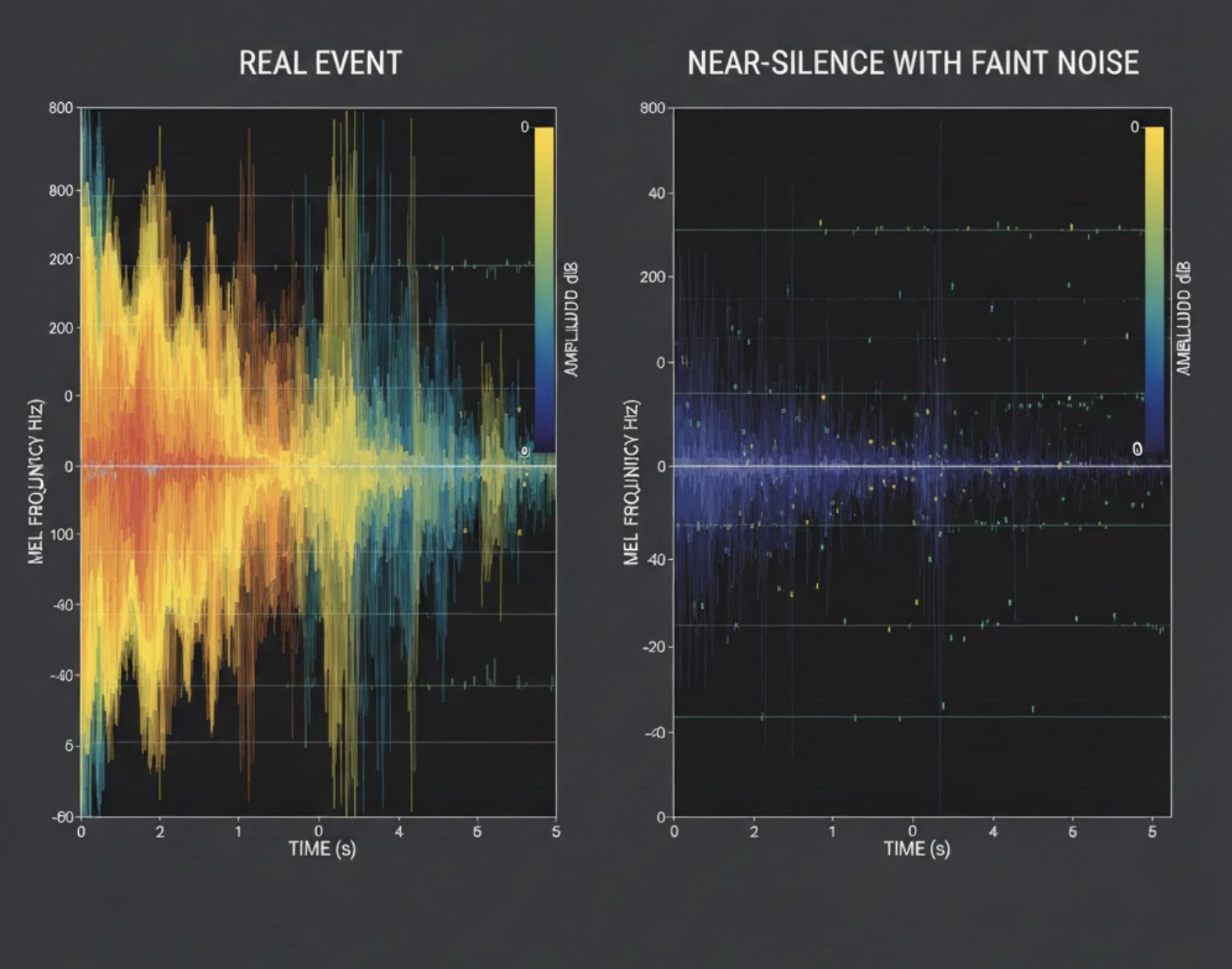

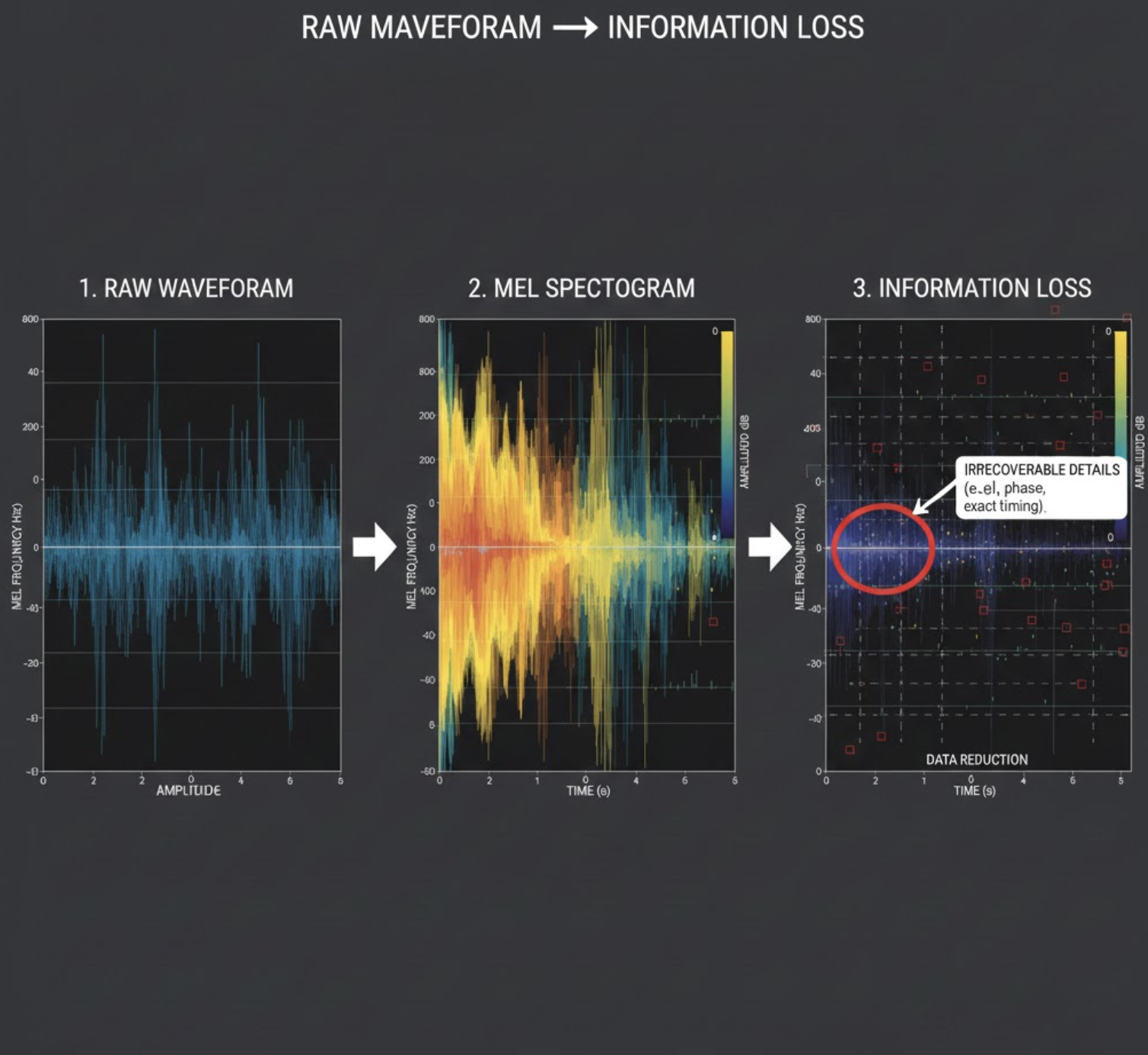

2. Mel spectrograms compress away semantics

Mel spectrograms:

- Emphasize energy patterns

- Compress frequency resolution

- Lose phase and temporal nuance

This means very different sounds can look similar once reduced to mel space—especially at low energy.

Silence plus a faint hum can look closer to a real event than you’d expect.

3. CNNs reward consistency, not meaning

MelCNN learned:

“Whenever I see this energy blob, I get rewarded.”

It didn’t learn what the sound was.

It learned what patterns paid off during training.

That’s where hallucination begins.

Detecting the Hallucination: False Positives Tell the Truth

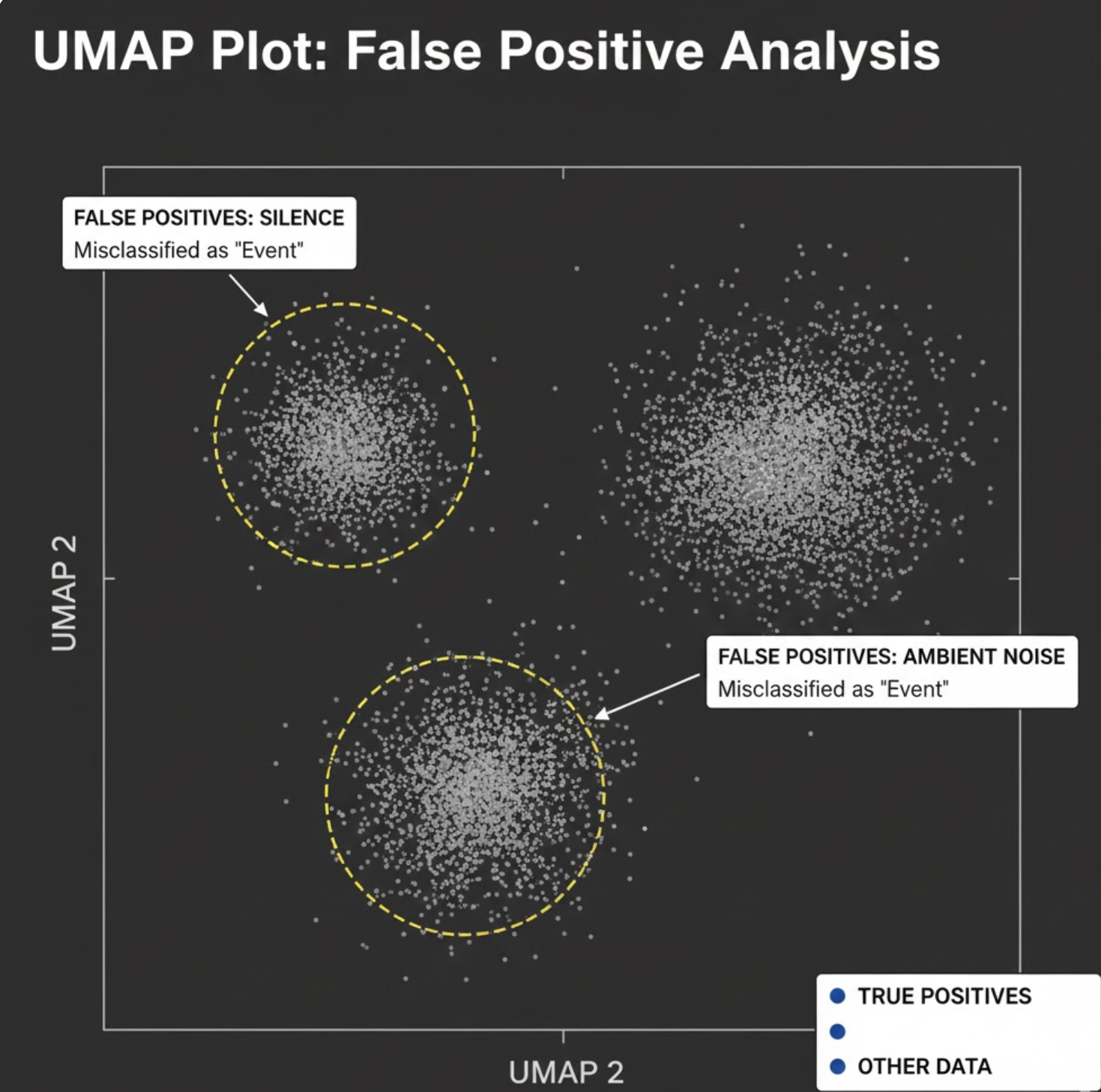

The breakthrough didn’t come from metrics—it came from false positive mining.

We took every false positive from real usage and asked:

- Where does this sit in embedding space?

- Does it form a cluster?

- What does it sound like?

What we found

- False positives were not scattered

- They formed tight, repeatable clusters

- Many clusters were dominated by:

- Silence + noise

- HVAC / fan sounds

- Low‑frequency room hum

- Transitional audio boundaries

This confirmed the model wasn’t unstable—it was consistently hallucinating the same ghost sounds.

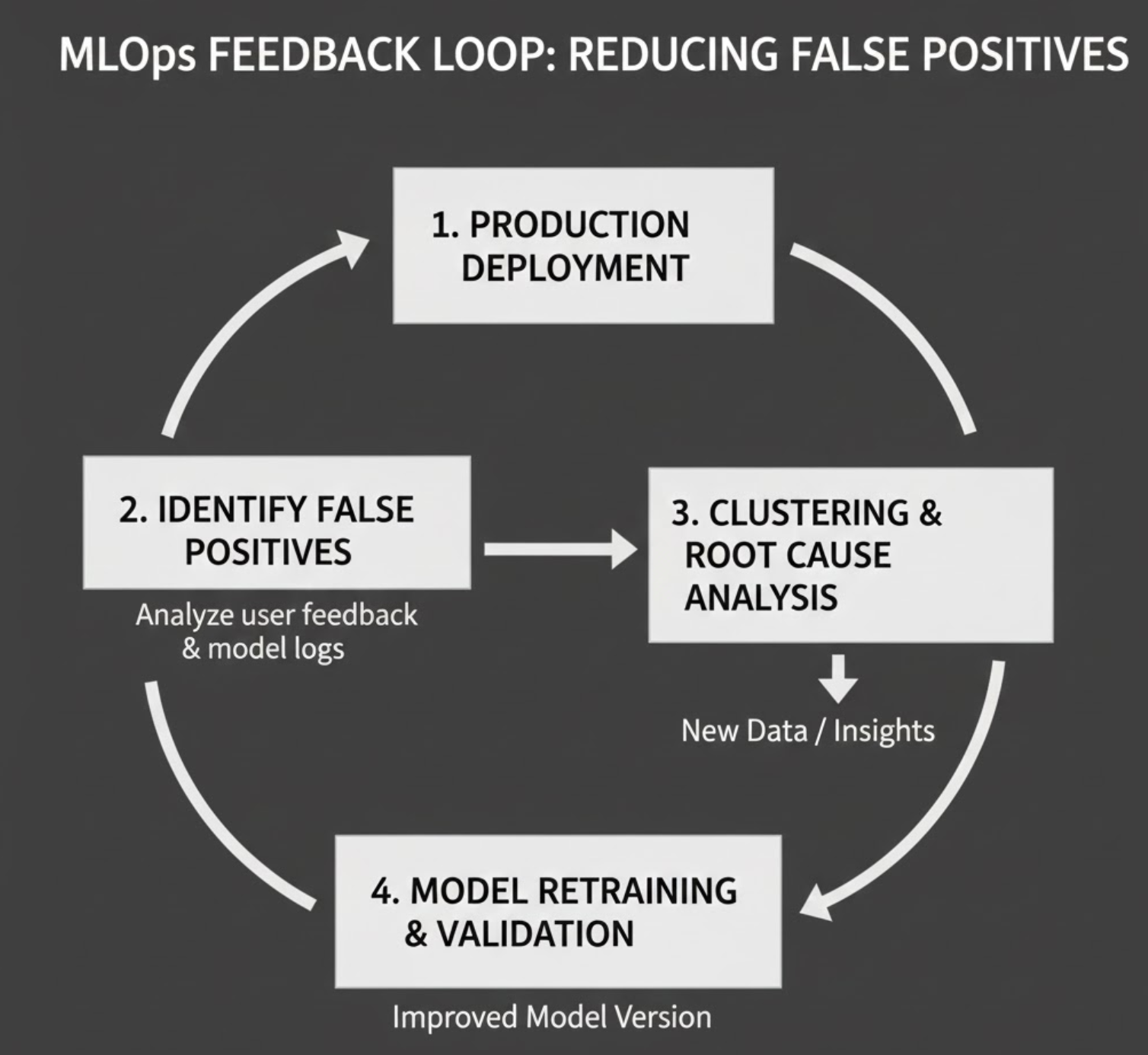

Fix #1: Explicit False Positive Mining

Instead of treating false positives as errors, we treated them as new data sources.

What we did

- Logged high‑confidence false positives from production

- Clustered them using embeddings

- Manually verified cluster themes (not every clip)

- Promoted clusters into:

neg_hardneg_silenceneg_ambient

This immediately changed the training dynamics.

The model was no longer rewarded for recognizing “almost sounds.”

Fix #2: Silence Is a First‑Class Concept

One subtle but critical change:

We stopped treating silence as absence of class.

Instead:

- Silence became an explicit negative concept

- We added multiple types of silence:

- Clean silence

- Noisy silence

- Transitional silence

- Device‑specific silence (mic noise floors)

This reduced ambiguity in the decision boundary.

The model learned:

“Low energy doesn’t imply a weak event—it usually means no event.”

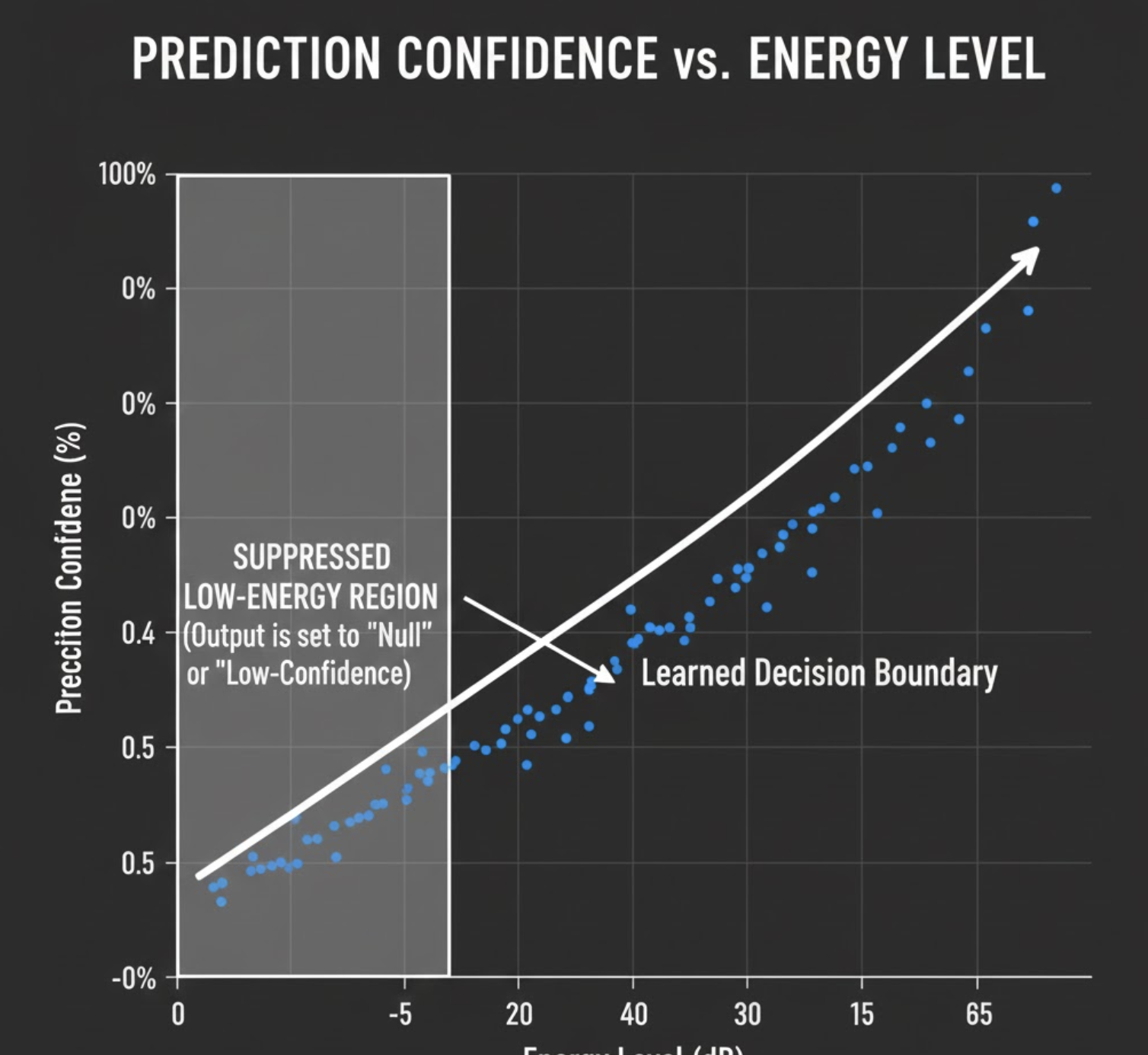

Fix #3: Energy‑Aware Training Signals

MelCNN was overly sensitive to faint activations. So we added energy‑aware constraints:

- Ignored predictions below a minimum RMS / energy threshold

- Penalized confident predictions on low‑energy frames

- Augmented training with:

- Gain jitter

- Background‑only mixes

- Artificial dropouts

This discouraged the model from treating noise as signal.

What Improved (And What Didn’t)

Improved significantly

- False positives on silence and ambient noise

- Prediction stability across environments

- Trust in high‑confidence outputs

Did NOT help much

- Simply adding more random negatives

- Increasing model depth

- Training longer

Hallucination wasn’t a capacity problem.

It was a data semantics problem.

Key Takeaways

- Audio hallucination looks like confidence, not randomness

- Clean spectrograms don’t guarantee clean labels

- Silence must be modeled, not ignored

- False positives are the best dataset you already have

- Validators beat bigger classifiers in production systems

MelCNN didn’t fail because it was weak.

It failed because it learned exactly what we taught it - including the ghosts hidden in our data.