Why Auto-Labeling Audio Needs Humans in the Loop

Machine learning promises automation at scale, but building reliable audio classification systems reveals a persistent challenge: ground truth validation. When we set out to build an edge-deployed dog sound classifier, we explored every path to automated labeling—and each one led back to the same conclusion: human perception isn't a fallback, it's a prerequisite.

The question wasn't whether automation could generate labels. It was whether those labels were correct.

The Edge Device Problem

Edge deployment fundamentally constrains your model choices. Unlike cloud-based systems that can throw compute at problems, edge devices demand small, efficient architectures—MelCNN, YamNet, or similarly compact models that fit within strict memory and latency budgets.

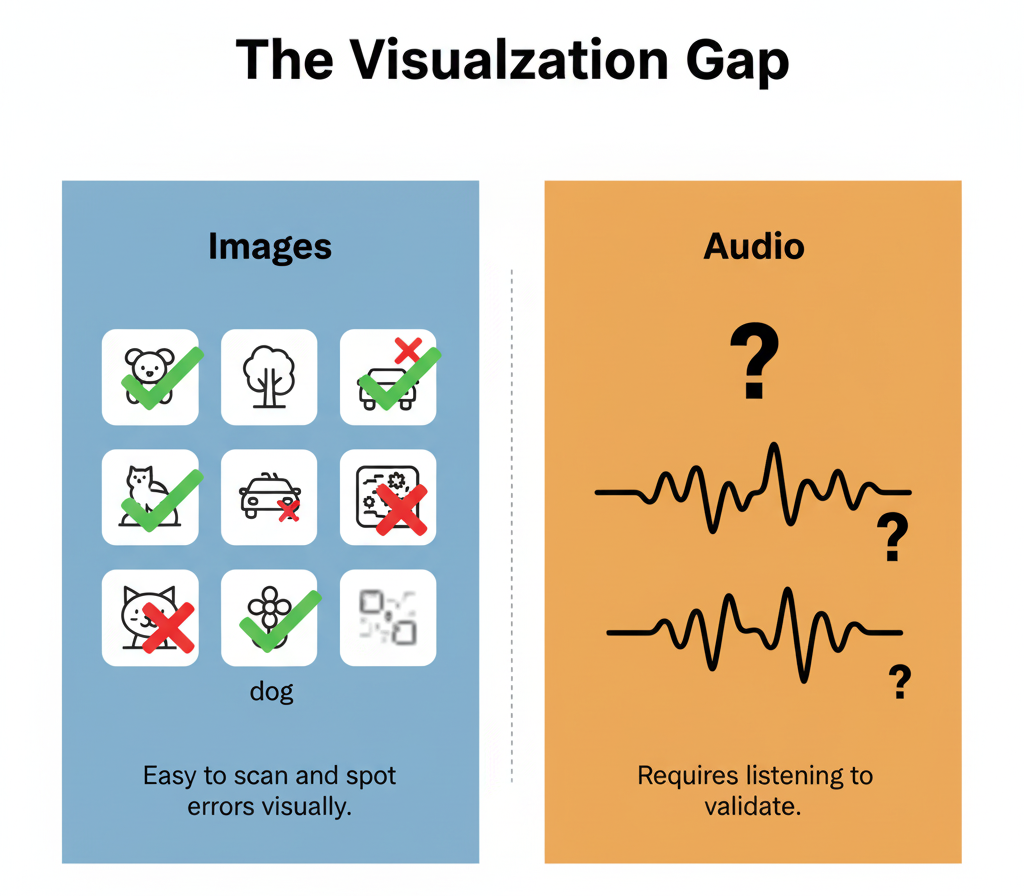

Training these student models requires high-quality labeled data. Not thousands of samples, but thousands of correctly labeled samples. In audio ML, that distinction matters more than in almost any other domain. Why? Because unlike images, audio labels aren't self-evident. You can't glance at a waveform and know what you're hearing. You have to listen.

This creates a fundamental validation problem that every approach to automated labeling must eventually confront.

The Landscape of Automated Labeling

When facing an unlabeled audio corpus, several paths seem viable. We evaluated each:

Approach 1: Foundation Model

The pitch: Use a large pre-trained model like CLAP (Contrastive Language-Audio Pretraining) to classify the entire dataset. CLAP, trained on massive audio-text pairs, can recognise thousands of sound categories. Point it at dog audio, get back labels, train your student model.

The appeal: Speed and scale. CLAP can process thousands of clips in hours. No human labor, no annotation interfaces, no bottlenecks.

The problem: How do you validate correctness? CLAP produces confident predictions, but confidence doesn't equal accuracy. When it labeled a vocalisation as "barking" versus "whining," we had no efficient way to verify at scale. Spot-checking revealed systematic issues—edge cases misclassified, ambiguous sounds forced into rigid categories, domain-specific contexts (home recordings, specific breeds) that CLAP's training didn't capture.

We could train a model on CLAP's labels, but without ground truth validation, we'd be teaching a student model to reproduce an unverified teacher's potential errors. The automation didn't solve the problem; it obscured it.

Approach 2: Weak Supervision and Label Propagation

The pitch: Manually label a small seed set with high confidence, then use semi-supervised learning techniques—label propagation, pseudo-labeling, or consistency regularisation—to expand coverage across unlabeled data.

The appeal: Minimise human effort to just the seed set. Let the model extrapolate patterns and generate labels for the remaining corpus.

The problem: Audio features are high-dimensional and context-dependent. A bark recorded indoors with reverberation looks spectrally different from the same bark outdoors. Label propagation assumes that similar embeddings deserve similar labels, but acoustic similarity doesn't always map to semantic similarity. A play-growl and an aggressive growl might cluster nearby in embedding space but require different labels for our use case.

Weak supervision can amplify the biases and edge-case failures of the seed set. Without validation, errors propagate silently. We'd need humans to validate the expanded labels anyway—at which point, why not validate more systematically?

Approach 3: Active Learning

The pitch: Train an initial model on a small labeled set, identify samples where the model is most uncertain, send those to human annotators, retrain, repeat. Focus human effort where the model needs it most.

The appeal: Efficient use of human time. Only label the informative samples—the decision boundaries, the ambiguous cases, the out-of-distribution examples.

The problem: Active learning optimizes for model improvement, not ground truth coverage. It identifies samples that confuse this particular model, but that's not the same as identifying samples where labels are objectively wrong or ambiguous. If your initial model inherited CLAP's systematic errors, active learning might focus attention on the wrong uncertainties.

More critically, audio active learning requires infrastructure: model training pipelines, uncertainty quantification, sample selection strategies, human annotation interfaces. For our edge deployment timeline, this complexity outweighed the benefits. We needed validated data now, not an iterative loop that might converge eventually.

Approach 4: Crowdsourced Annotation

The pitch: Upload clips to a crowdsourcing platform, distribute labeling across many annotators, aggregate results to reduce individual error.

The appeal: Parallelization and cost efficiency. Thousands of clips can be labeled simultaneously by a distributed workforce.

The problem: Audio annotation has a steep learning curve. What sounds like a "bark" to an untrained annotator might be categorically different to someone who understands canine vocalizations. Inter-annotator agreement drops dramatically without domain knowledge. We'd need extensive annotator training, quality control tasks, and majority-voting schemes—infrastructure overhead that defeats the purpose of crowdsourcing.

Worse, crowdsourcing introduces latency. For an iterative development process where label schemas evolve based on findings, waiting for external annotators to complete tasks and for quality control to catch errors creates unacceptable delays.

Why Human-in-the-Loop Won

After exploring alternatives, we converged on a hybrid approach: CLAP for initial labeling, humans for validation.

The Architecture

The pipeline combined automation's speed with human judgment's reliability:

- CLAP generates initial labels across the full corpus, producing classifications and confidence scores

- Strategic sampling identifies validation priorities:

- Low-confidence predictions (where CLAP was uncertain)

- Random samples from high-confidence predictions (to catch systematic errors)

- Edge cases flagged by heuristics (unusual duration, overlapping sounds, acoustic anomalies)

- Human validators review samples through a lightweight labeling tool—play audio, confirm or correct label, move on

- Validated dataset trains the edge model

Why This Worked

Speed without sacrifice: CLAP handled the bulk labeling that would've taken humans weeks. Humans focused only on validation, reducing annotation time by 10x versus manual labeling from scratch.

Ground truth confidence: Every label in the final dataset was either confirmed or corrected by a human. No uncertainty, no unverified predictions—just validated ground truth.

Iterative flexibility: When validators noticed patterns—"these labels conflate two distinct behaviors" or "this category needs subdivision"—we could adjust the taxonomy and re-validate affected samples. The tight feedback loop meant the dataset improved continuously.

Quality metrics: Where other approaches offered theoretical guarantees or convergence proofs, human-in-the-loop delivered measurable quality. We ran A/B tests: models trained on unvalidated CLAP labels achieved 73% accuracy on human-validated test data. Models trained on our hybrid pipeline achieved 89% accuracy. That 16-point gap represented the tangible value of ground truth rigor.

The Validation Bottleneck Is Real

What all automated approaches underestimate is the cost of not knowing if your labels are correct. You can train models on any labels—garbage in, model out. But deploying an audio classifier to edge devices in real-world environments means errors have consequences. A pet monitoring system that misclassifies distress calls isn't just inaccurate; it's potentially harmful.

Audio exacerbates this because validation is perceptually expensive. Computer vision engineers can scan grids of labeled images and spot errors in seconds. Audio requires sequential listening. You can't parallelise your perception. Every clip demands focused attention.

This makes validation the bottleneck—but it's a necessary bottleneck. The question isn't whether to validate. It's how to validate efficiently.

Human Perception as a Feature, Not a Bug

The ML industry often frames human involvement as technical debt—a temporary necessity until better algorithms eliminate the need. But in audio ML, human perception isn't a workaround. It's the ground truth.

CLAP doesn't "hear" audio. It processes spectral features and predicts labels based on training patterns. When it classifies a vocalisation, it's performing pattern matching, not semantic understanding. Humans bring context: is this bark playful or aggressive? Is this silence, or is there low-frequency content below the mic's threshold? Does this label match the purpose of the classifier we're building?

Foundation models can propose labels. Only humans can validate them in context.

The Broader Pattern

This isn't unique to audio. Any domain with subjective labels, context-dependent classifications, or ambiguous ground truth faces the same challenge:

Medical imaging: Radiologists argue about borderline cases. Automated labeling can't resolve disagreements; it can only reflect majority patterns in training data.

NLP sentiment analysis: "This product is... something" could be sarcasm, understatement, or ambivalence. Context determines sentiment, and context requires human judgment.

Autonomous vehicles: Is that a pedestrian about to cross, or standing at the curb? Edge cases kill automated labeling because they're inherently ambiguous.

In every case, automated labeling offers scale. Human validation offers certainty. You need both.

Key Takeaways

Foundation models are powerful proposers, not validators: CLAP-scale models can generate labels at scale, but they can't verify their own correctness. Confidence scores aren't ground truth.

Weak supervision and active learning defer the validation problem: These techniques extend labeling coverage, but someone still needs to verify correctness. In audio, that verification is perceptually expensive and irreducible.

Human-in-the-loop isn't compromise—it's optimization: Focus automation on bulk labeling and human judgment on validation. This preserves quality while achieving scale.

Ground truth quality is measurable: The 16-point accuracy gap between validated and unvalidated training data proves that dataset quality directly determines model performance. There's no algorithmic substitute for correct labels.

Audio demands perceptual validation: Unlike visual data, audio can't be validated by glancing. You have to listen. This makes human involvement non-optional for any audio ML pipeline that prioritizes reliability over speed.

The future of audio ML isn't eliminating humans—it's positioning them where their perception creates irreplaceable value.