CAN Messages as Contracts: Headers, Packing, and Designing Buses That Age Gracefully

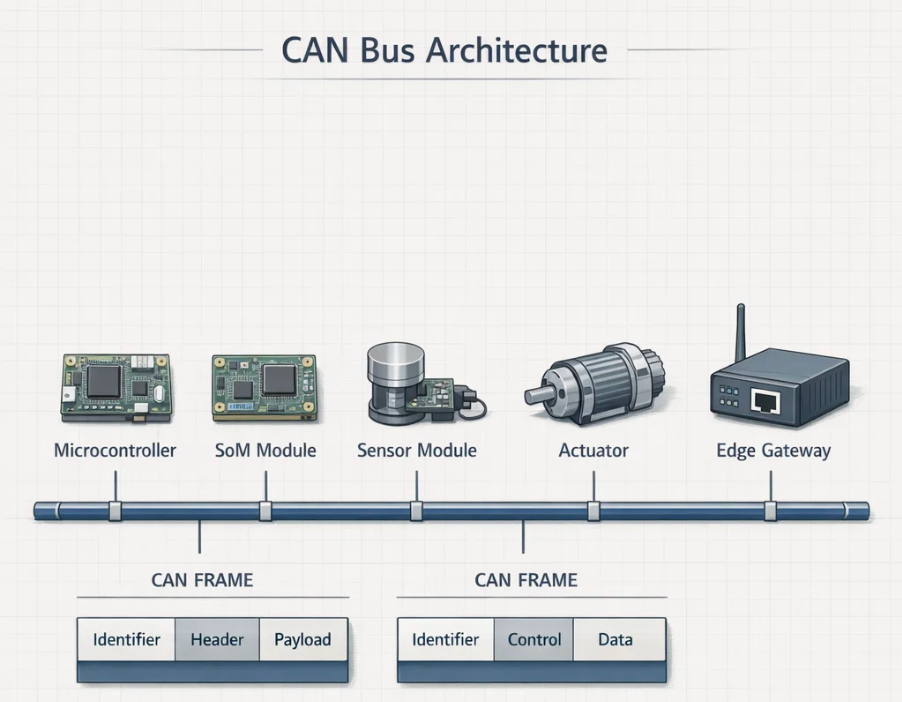

Controller Area Network (CAN) is often introduced as a “simple” fieldbus—ID, DLC, payload, done. In real systems, that simplicity hides a deeper reality: CAN messages become long-lived contracts between firmware, hardware, gateways, and cloud pipelines. This article reframes CAN not as a transport, but as a shared language—where identifier structure, header semantics, bit-level packing, and evolution strategy determine whether a system remains debuggable and scalable years later. Drawing from multi-node, SoM-based device fleets, it explores how message ownership, signal grouping, endian decisions, versioning, and backward compatibility shape bus health under real load. The goal is to help engineers design CAN schemas that survive feature growth, partial upgrades, and mixed-generation nodes—without bus churn or silent data corruption.

Problem: CAN Is Simple - Until It Isn’t

CAN’s elegance is its greatest strength and its quietest trap. An arbitration ID, a payload of up to eight bytes (or more with CAN FD), and a checksum—what could go wrong?

The problem appears not on day one, but on year three. New nodes join the bus. Old nodes remain deployed. Gateways evolve. Cloud pipelines expect stability. Suddenly, a “simple” message becomes a dependency web spanning firmware releases, hardware revisions, and analytics logic.

At that point, CAN frames stop being packets and start being promises.

Promises about meaning. About layout. About how a value will be interpreted tomorrow by a node that hasn’t been updated yet.

When those promises are implicit—or worse, undocumented—the bus begins to age poorly.

Why It Matters: Buses Outlive Firmware Teams

In most embedded systems, CAN outlives individual firmware implementations. Hardware stays in the field. Gateways aggregate data for years. Cloud services are refactored by engineers who never touched the original device.

A CAN message designed without evolution in mind becomes brittle. A field repurposed “just this once” breaks a downstream consumer silently. A packed bitfield optimized for bandwidth becomes impossible to extend.

In multi-device ecosystems—where trackers, sensors, actuators, and gateways must interoperate—the bus is the shared memory of the system. Treat it casually, and technical debt accumulates invisibly.

Treat it as a contract, and the system remains debuggable long after the original design context fades.

Architecture: Thinking in Contracts, Not Frames

The mental shift is simple but profound: design CAN messages the way you design public APIs.

That means:

- Clear ownership

- Explicit semantics

- Stable headers

- Evolution paths that don’t break existing consumers

Instead of asking, “How do I fit this signal into eight bytes?”

Ask, “How will this message be understood by a mixed-generation system five years from now?”

This perspective changes how you structure identifiers, headers, and payloads.

Identifier Strategy: More Than Just Arbitration

The CAN ID is often treated as a numeric label. In contract-driven systems, it becomes a namespace.

Well-designed identifiers encode category, not implementation. For example, separating:

- Telemetry vs. control

- Periodic vs. event-driven

- Node-originated vs. gateway-originated messages

This allows receivers to reason about intent before parsing payloads.

It also enables selective filtering at gateways and diagnostic tools—critical when buses grow dense.

Good IDs reduce the need to inspect payloads just to know what’s happening.

Headers: The Most Underrated Bytes on the Bus

If CAN messages are contracts, headers are the legal clauses.

A small, consistent header—present across message families—pays dividends:

- Version: Signals how to interpret the rest of the payload

- Flags: Indicate optional fields or modes

- Sequence or freshness markers: Help detect stale data or drops

These bytes are often sacrificed in the name of “saving space.” In reality, they save engineering time for years.

A stable header allows you to extend payloads without redefining meaning. Older nodes can ignore what they don’t understand, while newer nodes unlock richer semantics.

The absence of headers forces receivers to infer meaning from position alone—fragile under change.

Packing: Optimize for Meaning, Not Density

Bit-level packing is seductive. It feels efficient. It looks clever. It often ages poorly.

The real cost of dense packing is not CPU cycles—it’s human comprehension.

When designing payloads:

- Group signals that evolve together

- Avoid cross-cutting bitfields shared by unrelated concepts

- Prefer byte alignment when evolution is likely

Endianness should be explicit and consistent. Mixing conventions across messages guarantees confusion when logs are analyzed months later.

Bandwidth is finite, but cognitive load is the true bottleneck.

In systems where telemetry flows from device → gateway → cloud, clarity beats micro-optimization.

Ownership: Every Message Needs an Owner

One of the fastest ways to rot a CAN bus is shared ownership.

When multiple nodes feel free to “adjust” a message because they all “use it,” contracts dissolve. Subtle changes propagate silently.

A simple rule prevents this:

Every CAN message has exactly one owner.

The owner defines:

- Payload structure

- Field semantics

- Evolution rules

Consumers adapt, but they do not redefine.

This mirrors how distributed systems handle schema ownership—and for good reason. CAN buses are distributed systems, just with fewer megabytes and more real-time constraints.

Evolution: Designing for Partial Upgrades

In real fleets, not everything updates at once.

Some nodes remain on older firmware. Some gateways lag. Some tools are pinned to previous schemas. Your CAN design must tolerate this.

Practical strategies include:

- Versioned headers rather than versioned IDs

- Optional fields guarded by flags

- Additive changes instead of destructive repurposing

When removal is unavoidable, deprecate first. Let messages coexist. Silence is worse than redundancy.

This is where treating CAN as a contract pays off. Contracts evolve—but rarely break overnight.

Where This Fits in IoT: The Bus as a Spine

In connected products, CAN rarely lives alone.

It feeds gateways, which bridge to wireless links, which ultimately land in cloud pipelines. Any ambiguity at the bus level multiplies downstream.

At Hoomanely, for example, a modular, SoM-based ecosystem connects multiple device types—wearable trackers, sensing peripherals, and edge gateways—each responsible for a slice of the pet’s behavioral picture. These devices differ in capability and lifecycle, yet must interoperate reliably.

In such systems, CAN becomes the spine:

- Devices publish raw and derived signals

- Gateways aggregate and contextualize

- Cloud services analyze and learn

A contract-driven CAN schema allows this pipeline to remain stable even as individual devices evolve independently.

The bus doesn’t just move bytes—it preserves meaning across layers.

Real-World Usage: Debugging Years Later

The true test of a CAN design is not throughput—it’s debuggability.

When a field issue arises years after launch, engineers rely on:

- Logs

- Captured frames

- Historical knowledge

A well-designed contract allows someone unfamiliar with the original implementation to infer intent quickly. Headers explain versions. IDs explain categories. Payloads read like structured data, not puzzles.

In contrast, opaque packing forces tribal knowledge. When that knowledge leaves, the system becomes unmaintainable.

Graceful aging is not accidental—it is designed.

Takeaways: Designing CAN That Lasts

- Treat CAN messages as contracts, not packets

- Use IDs as namespaces, not just priorities

- Invest in small, consistent headers

- Pack for clarity before density

- Assign single ownership per message

- Design explicitly for mixed-version systems

When done well, CAN stops being a fragile wire protocol and becomes a stable language—one that hardware, firmware, gateways, and cloud systems can speak together for years.

That is how buses age gracefully.