Embedded Filesystems as System Contracts: Designing Storage That Survives Power Loss, Scale, and Time

Filesystems in embedded systems are often treated as implementation details—picked late, configured minimally, and rarely revisited. In reality, a filesystem becomes a long-lived contract between firmware, storage media, update mechanisms, and the data pipelines built on top of it. This article reframes embedded filesystems not as storage utilities, but as architectural decisions that shape reliability, recovery behavior, write amplification, and system observability over years of operation. Drawing from multi-device, SoM-based products that log telemetry, configuration, media, and state under real-world constraints, it explores how different filesystem models behave under power loss, constrained flash, partial upgrades, and evolving product requirements. The goal is to help engineers choose and design filesystem strategies that remain predictable, debuggable, and maintainable as systems grow.

Problem: Filesystems Chosen Late, Paid for Early

In many embedded projects, the filesystem is chosen near the end of bring-up.

The hardware boots, sensors stream data, the cloud path works—and only then does storage get added.

At first, it seems harmless. A lightweight filesystem is picked, a few mount flags are set, and logging “just works.” But months later, storage becomes the place where issues surface: corrupted state after power loss, unexplained wear on flash, partial updates that don’t roll back cleanly, or logs that disappear when you need them most.

The root issue is simple: filesystems are treated as utilities, not as system contracts.

Once deployed, a filesystem silently defines:

- What happens when power drops mid-write

- Whether configuration survives partial updates

- How recovery behaves after resets

- How observable failures are when things go wrong

By the time problems show up, the contract is already in production.

Why It Matters: Storage Is Where Time Accumulates

Unlike sensors, radios, or processors, storage accumulates history.

It carries state across boots, firmware versions, and environmental conditions.

In long-lived IoT systems, the filesystem sits at the intersection of:

- Firmware behavior

- Flash endurance

- OTA and rollback mechanisms

- Telemetry and debugging workflows

At Hoomanely, this became clear while operating a multi-device, SoM-based ecosystem: trackers capturing movement and environmental context, smart bowls recording weight, sound, and visual signals, and an edge gateway aggregating and interpreting data locally before cloud upload. Each device class writes different kinds of data—some ephemeral, some long-lived—but all depend on storage behaving predictably across resets, upgrades, and field conditions.

A filesystem choice made early ends up shaping how confidently you can:

- Recover devices remotely

- Debug issues weeks after they occurred

- Evolve data formats without bricking old units

The filesystem doesn’t just store data—it stores assumptions.

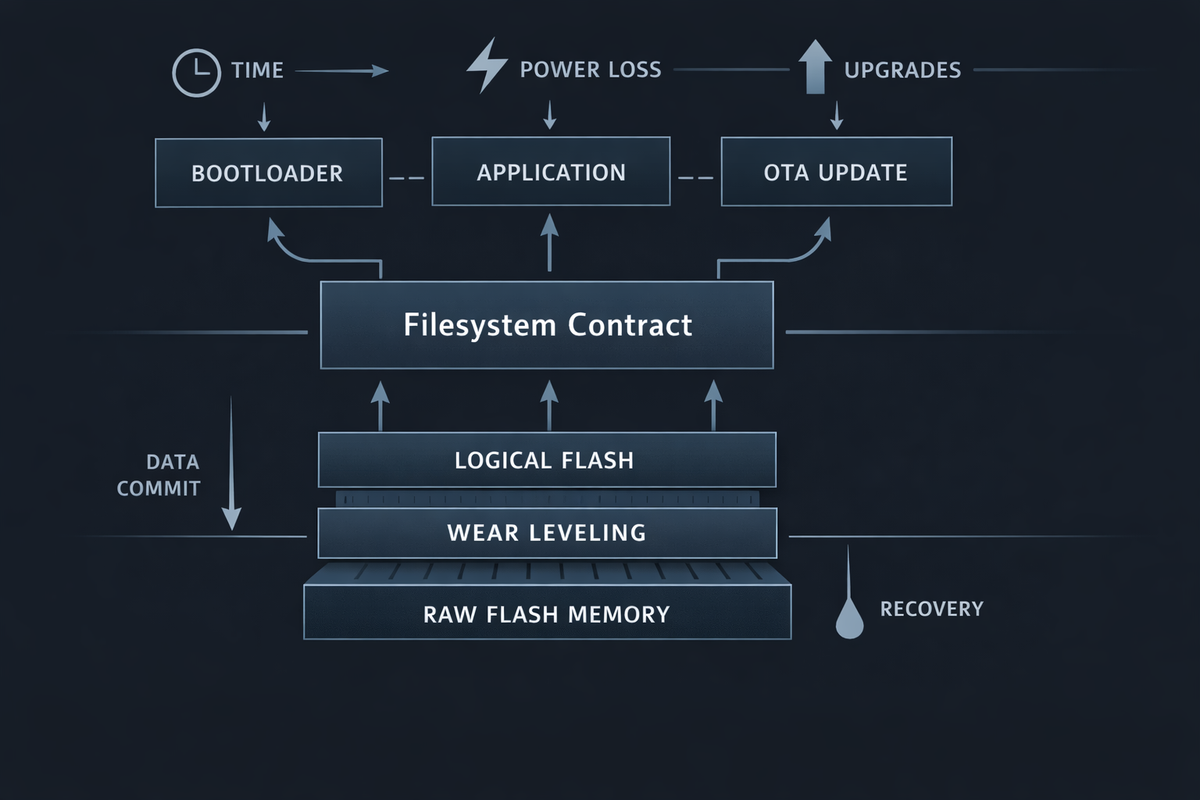

Architecture: Thinking of Filesystems as Contracts

A useful way to reason about embedded filesystems is to treat them as contracts between layers.

The contract defines:

- What guarantees are provided (atomicity, ordering, persistence)

- What is explicitly not guaranteed

- How violations are surfaced (silent corruption vs explicit failure)

This contract spans four layers:

- Storage Medium

NOR flash, NAND flash, eMMC, or SD all have different erase models, alignment constraints, and failure modes. - Filesystem Model

Log-structured, copy-on-write, block-mapped, or key-value oriented. - Firmware Access Patterns

Append-only logs, frequent rewrites, small config updates, or mixed media storage. - Operational Reality

Power loss, brownouts, watchdog resets, partial OTA updates, and field debugging.

When these layers are aligned, systems age gracefully.

When they’re mismatched, issues surface slowly—and often irreversibly.

How It Works: Filesystem Models Under Real Constraints

Rather than comparing filesystems by features, it’s more useful to compare them by behavior under stress.

Log-Structured Models

These systems treat storage as an append-only log, writing new data sequentially and reclaiming space later.

What they’re good at

- Power-loss resilience

- Predictable write behavior

- Clear recovery semantics

What they trade off

- Write amplification over time

- Garbage collection complexity

- Less intuitive on-flash layout

They work well when firmware treats storage as a stream of facts rather than mutable files.

Copy-on-Write Models

Updates create new versions of data rather than modifying blocks in place.

Strengths

- Strong consistency guarantees

- Safe updates without in-place corruption

Challenges

- Metadata growth

- Fragmentation under frequent small updates

- Harder to reason about long-term wear without discipline

These models reward careful partitioning and clear ownership of files.

Block-Mapped or Traditional Models

These behave more like desktop filesystems, with in-place updates and block tables.

Advantages

- Familiar semantics

- Simple mental model

Risks

- Vulnerable to mid-write power loss

- Recovery may require scanning or repair

- Silent corruption is harder to detect

They demand external safeguards if used in power-unstable environments.

Real-World Usage: Designing Storage Roles, Not Just Mount Points

One of the most valuable shifts is to stop thinking in terms of “a filesystem” and start thinking in terms of storage roles.

In multi-device systems, storage naturally separates into roles:

- Configuration State

Small, critical, rarely written. Must survive partial updates. - Operational Logs

Append-heavy, disposable, useful mainly for debugging and observability. - Derived State

Cached results or intermediate data that can be rebuilt. - Media or Bulk Data

Larger, less frequent writes with different lifetime expectations.

At Hoomanely, operating across trackers, smart devices, and an edge gateway reinforced this separation. Each device writes different categories of data, but the contract is consistent: configuration is sacred, logs are append-only, derived state is disposable.

This separation enables:

- Independent failure domains

- Clear recovery strategies

- Easier OTA evolution

Power Loss: Designing for the Worst Case, Not the Happy Path

Power loss isn’t an edge case in embedded systems—it’s the default failure mode.

A filesystem contract should answer:

- What data is guaranteed to survive?

- What data may be lost?

- How does firmware detect incomplete operations?

Good designs embrace loss explicitly:

- Logs may truncate, but never corrupt prior entries

- Config updates are atomic or versioned

- Recovery paths are deterministic

Bad designs pretend power loss is rare—and pay for it later.

One practical pattern is versioned writes: write new state alongside old, then switch pointers only after completion. This makes recovery boring—and boring is good.

Scale and Time: Filesystems Outlive Features

Most embedded systems ship with far fewer features than they’ll have a year later.

Over time:

- Data schemas evolve

- Logs grow more complex

- New subsystems want storage access

A filesystem contract should allow:

- Forward-compatible data formats

- Partial upgrades without full wipes

- Clear ownership boundaries

This is where SoM-based architectures help. When hardware and firmware platforms are shared across devices, storage behavior becomes part of the platform contract, not an individual product decision. The filesystem strategy chosen once must hold up across trackers, smart peripherals, and edge gateways.

Designing for time means asking:

If I read this flash five years from now, will I understand what I’m seeing?

Observability: When Storage Is Also a Debug Tool

Storage is often the only witness to failures that never reach the cloud.

A well-designed filesystem contract:

- Makes corruption visible, not silent

- Preserves failure context across resets

- Enables post-mortem analysis

Append-only logs, structured records, and clear boundaries between valid and invalid data turn storage into a debugging ally rather than a liability.

If you can’t trust your storage, you can’t trust your diagnosis.

Takeaways: Designing Filesystems That Age Well

A few principles consistently hold up in long-lived embedded systems:

- Treat the filesystem as an architectural decision, not a library choice

- Design explicit storage roles with different guarantees

- Assume power loss will happen at the worst possible moment

- Make recovery boring and predictable

- Optimize for debuggability, not just performance

- Think in years, not firmware releases

When storage contracts are clear, systems scale calmly.

When they’re implicit, systems accumulate risk quietly—until they don’t.

The most reliable embedded systems aren’t the ones with the fanciest filesystems.

They’re the ones where everyone understands what the filesystem promises—and what it doesn’t.