Pushing the Edge: Architecting High-Bandwidth Sensor Buffering with FMC & External PSRAM

In embedded systems, we often celebrate the idea of doing more with less. Smaller MCUs, tighter power budgets, fewer components efficiency as a virtue. But once you start building real device fleets at the edge, that philosophy quickly meets its limits.

At Hoomanely, our devices don’t just sample a sensor and sleep. They fuse high-resolution visual data, thermal imagery, and continuous environmental signals to infer real-world pet behavior. When a system needs to ingest bursts of rich sensor data in milliseconds—while remaining reliable for years—“less” is no longer the constraint. Architecture is.

A modern microcontroller may offer hundreds of kilobytes of internal SRAM. That sounds ample—until you start buffering raw image frames alongside thermal arrays and event metadata. At that point, memory stops being a resource and becomes a battlefield.

The obvious answer is external RAM. The real answer is learning how to survive it.

This article walks through how we architected a high-bandwidth buffering subsystem using FMC-attached PSRAM, the failures we encountered under real load, and the software patterns that allowed the system to age gracefully in the field.

The Problem: The Speed-vs-Space Paradox

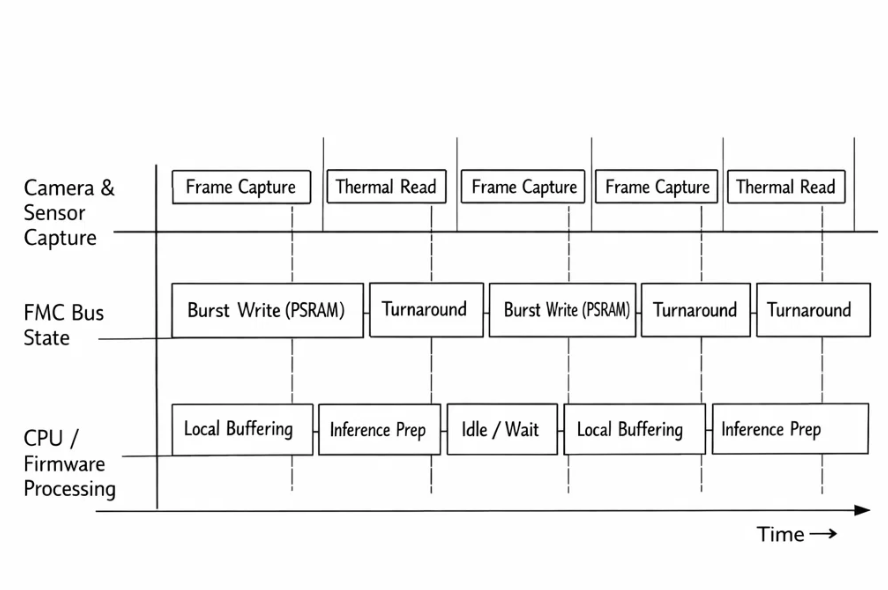

Edge devices like EverBowl and EverHub live in bursts.

They wake up, ingest a flood of sensor data, make decisions locally, and then either discard or forward results upstream. Internal SRAM is perfect for control logic—but completely inadequate as a scratchpad for uncompressed image or thermal buffers.

Streaming directly to Flash was never an option. Latency is unpredictable, write endurance becomes a liability, and filesystem overheads introduce jitter exactly where timing matters most.

What we needed was:

- Large, fast, volatile storage

- Predictable write behavior

- Zero long-term wear concerns

External PSRAM connected over the MCU’s Flexible Memory Controller (FMC) fit perfectly—on paper.

Memory-mapped, simple addressing, no drivers required. Write to an address, data appears. But sustained, high-frequency access quickly exposed a harsher truth: external memory behaves like a bus-attached peripheral, not real RAM.

Under load, we encountered two systemic failures:

- Bus contention when rapidly switching between read and write operations

- Data corruption manifesting as consistent byte-level misalignment during high-throughput DMA bursts

These weren’t random glitches. They were architectural mismatches.

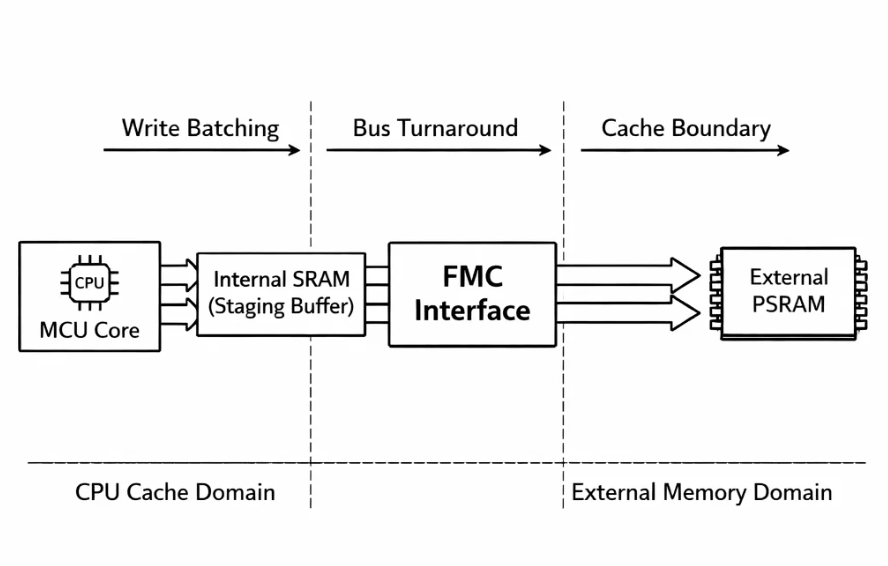

The Architecture: FMC as a High-Speed Bridge, Not a Shortcut

The turning point came when we stopped treating PSRAM as “more RAM” and started treating it as a high-speed, block-oriented device.

Instead of letting the compiler freely touch external memory, we inserted a deliberate buffering layer between fast internal SRAM and the slower, timing-sensitive FMC bus.

The FMC was configured in NORSRAM mode with relaxed timing margins—not to chase peak throughput, but to maximize stability across temperature, voltage, and aging. But configuration alone wasn’t enough. The real gains came from software discipline.

Implementation: The “Chunk and Flush” Pattern

At the heart of our PSRAM driver is a simple idea: never mix reads and writes at fine granularity.

1. Defeating Bus Contention

Every read-to-write transition on the FMC incurs a turnaround penalty. Code that casually reads a word, modifies it, and writes it back thrashes the bus and collapses throughput.

Our solution was a Chunk and Flush strategy:

- Read or generate data into a fixed-size internal SRAM buffer

- Perform all computation locally

- Burst-write the buffer back to PSRAM in one aligned transaction

This keeps the FMC bus in a single direction for long stretches, eliminating unnecessary stalls.

Internally, this meant:

- Fixed-size chunking

- Strict alignment

- Explicit memory barriers to enforce ordering

The result wasn’t just faster—it was predictable.

2. Cache Coherency: The Silent Saboteur

External memory plus DMA introduces a classic embedded trap: cache incoherency.

When DMA writes directly to PSRAM, the CPU’s data cache has no idea the contents changed. Without intervention, the processor happily reads stale data and propagates corruption upstream.

We adopted a strict rule:

Any PSRAM region touched by DMA must be treated as non-authoritative until cache lines are explicitly invalidated.

Before every CPU read, we invalidate the corresponding D-Cache range. Critically, we discovered edge cases where invalidation had to begin slightly before the expected address range to catch partial cache lines—small details that only surface under sustained stress.

Cache stopped being “helpful magic” and became a first-class system responsibility.

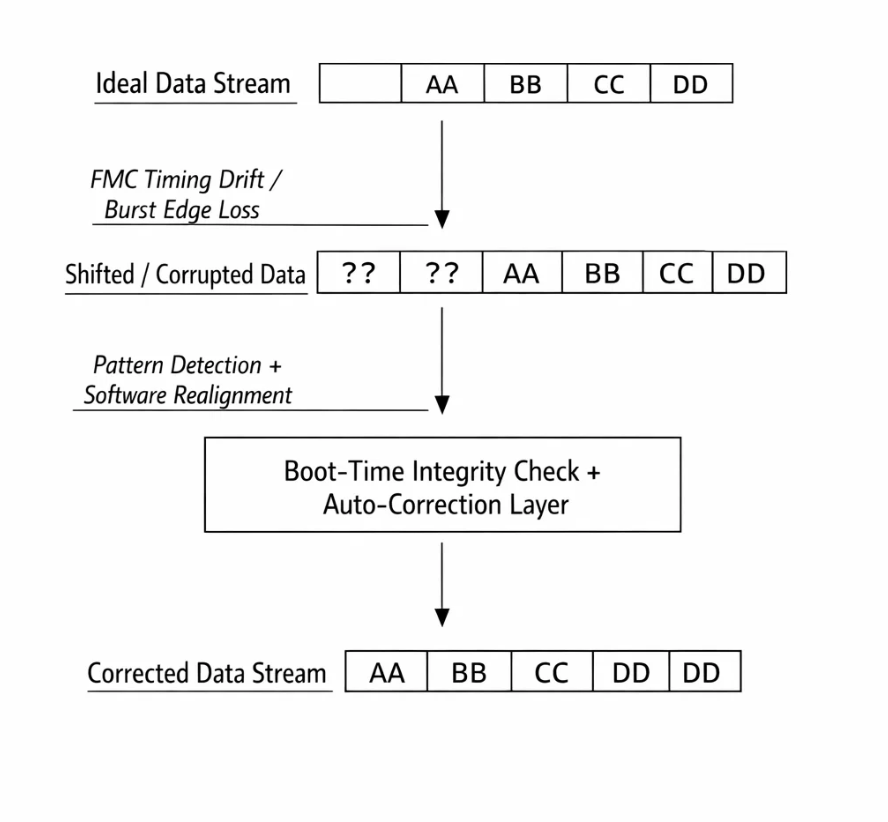

3. The “+2 Byte Shift” and Defensive Engineering

The most humbling failure was also the most educational.

Under specific operating conditions—temperature, timing drift, long-running uptime—we observed a consistent +2 byte shift in PSRAM data streams. Not noise. Not randomness. A clean, repeatable misalignment.

Rather than slowing the entire bus or tightening margins to the point of fragility, we treated this as a detectable failure mode.

At boot:

- A known signature pattern is written to a reserved PSRAM region

- The pattern is read back and verified

- If a shift is detected, a transparent software realignment layer is enabled

The system adapts to its own physical reality—without user intervention or device failure.

Real-World Usage: Buffering Across the Hoomanely Ecosystem

This architecture quietly underpins the entire Hoomanely edge stack.

When an EverBowl detects interaction, it rapidly buffers a burst of visual frames into PSRAM while simultaneously logging thermal and audio-derived events. Internal SRAM remains free for control logic, inference scheduling, and safety checks.

EverHub, acting as an edge gateway, uses the same buffering patterns to absorb telemetry bursts from multiple sources before making local decisions or forwarding summarized data to the cloud.

Because the buffering layer respects physical constraints—bus direction, cache boundaries, alignment—the system remains stable even as firmware evolves and workloads change.

Takeaways

High-bandwidth embedded buffering is not about squeezing cycles—it’s about respecting physics.

Key lessons we carry forward:

- Treat external RAM like a peripheral. Design drivers that understand buses, not just addresses.

- Batch aggressively. Direction changes are more expensive than raw throughput.

- Align everything. Misalignment in external memory systems breeds undefined behavior.

- Assume drift. Aging, temperature, and tolerance stack-ups are real—build detection, not denial.

- Own the cache. If DMA is involved, cache coherency is your job.

By architecting for reality instead of idealized datasheets, external PSRAM transformed from a liability into a reliable backbone—one that lets our devices push the edge without falling off it.