Ring Buffers as Contracts: Why State Machines Matter More Than Buffer Size

When your camera produces data faster than your bus can consume it, buffer sizing alone won't save you. The real problem is state ownership—and the bars in your images prove it.

The Problem: When Fast Producers Meet Slow Consumers

In multi-stage embedded pipelines, timing mismatches are inevitable. A camera sensor might capture a full frame in under 200ms, while offloading that data to flash storage takes nearly a second. During that second, what happens to the next frame? And the one after that?

The naive answer is "use a bigger buffer." The real answer is: you need a contract.

At Hoomanely, our SoM-based imaging devices face this exact challenge. When an EverBowl captures thermal and visual data for pet behavior inference, that data flows through multiple stages: DMA capture, PSRAM staging, flash storage, and eventually CAN FD transmission to an edge gateway. Each stage operates at a different speed. The camera doesn't wait for flash. Flash doesn't wait for CAN. And yet, somehow, the data needs to stay coherent.

The symptom we saw was subtle but devastating: garbage bars cutting through otherwise perfect images. Not corruption from a bad sensor. Not noise from electrical interference. Buffer reuse while data was still in flight.

The camera was writing new frames into the same memory region that the offload process was still reading from. Classic race condition. But why did a ring buffer—designed specifically to solve this problem—fail to prevent it?

Why It Matters: Contracts vs. Capacity

Most engineers think of ring buffers as a capacity problem: "How many buffers do I need to avoid blocking the producer?" But capacity is only half the story. The real question is: When is it safe to reuse a buffer?

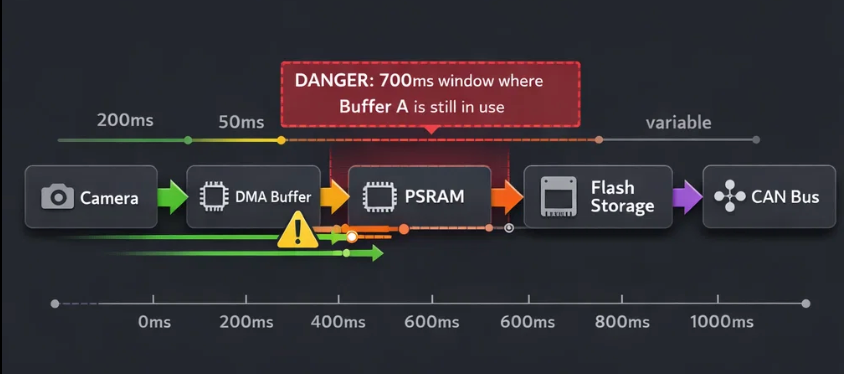

Consider a simple imaging pipeline:

- DMA writes frame data into Buffer A (200ms)

- Firmware copies Buffer A → PSRAM (50ms)

- Firmware offloads PSRAM → Flash (700ms)

- CAN transmits Flash → Gateway ( seconds)

If you release Buffer A after step 2, you've created a 700ms window where the camera might overwrite data that flash storage is still reading. If you wait until step 4, you've serialized your entire pipeline—no parallelism, terrible throughput.

The key insight: Buffer release isn't a timing problem. It's a state ownership problem. Each stage needs to explicitly declare: "I'm done with this data. The next stage can proceed."

This is why ring buffers in real systems need state machines. Not just indices and sizes, but lifecycle contracts that make ownership transitions explicit and auditable.

Architecture: State as a Contract

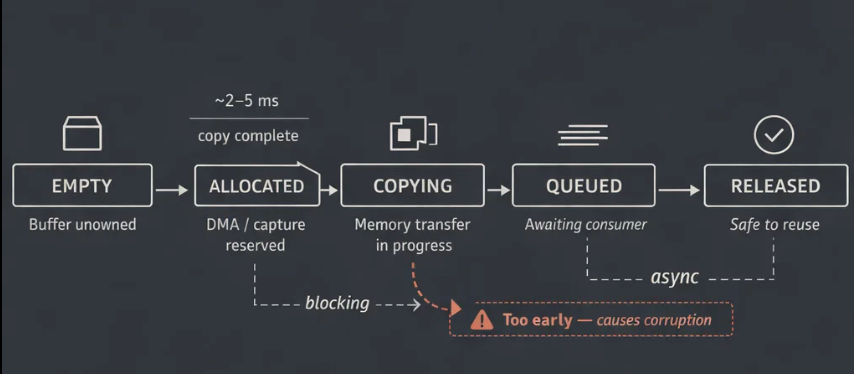

Our solution treats each buffer as having an explicit lifecycle, enforced by a state machine:

EMPTY → ALLOCATED → COPYING → QUEUED → RELEASED → EMPTY

Each transition represents a contract between stages:

- EMPTY → ALLOCATED: DMA owns this buffer. Camera can write.

- ALLOCATED → COPYING: DMA finished. Firmware is copying to PSRAM.

- COPYING → QUEUED: PSRAM copy done. Offload process can read.

- QUEUED → RELEASED: Flash write complete. Buffer is safe to reuse.

- RELEASED → EMPTY: Cleanup done. Buffer returns to pool.

The critical decision: when to transition QUEUED → RELEASED. Initially, we released after PSRAM copy (step 2). This created the race condition. The fix: release only after flash write completes (step 3).

This meant offload had to callback the ring buffer when done:

Offload completion handlervoid on_flash_write_complete(uint32_t sequence_id) { dma_ring_buffer_release(sequence_id); // NOW safe to reuse}

Why does this work? Because flash storage is the last synchronous consumer of the camera data. CAN transmission happens from flash storage, not from the ring buffer. Once data hits flash, the DMA buffer has served its purpose.

Key principle: Release buffers when the fastest stage that needs them is done. Not when the slowest downstream consumer finishes.

Implementation: Making States Auditable

State machines are only useful if they're observable. When debugging race conditions, you need to know: Which buffer was in which state when the corruption happened?

We made state transitions logged and indexed:

typedef enum { BUFFER_STATE_EMPTY = 0,

BUFFER_STATE_ALLOCATED,

BUFFER_STATE_COPYING,

BUFFER_STATE_QUEUED,

BUFFER_STATE_RELEASED} buffer_state_t;

typedef struct {

buffer_state_t state;

uint32_t sequence_id; // Links to capture event

uint32_t allocated_tick; // When allocated uint32_t released_tick; // When released

} dma_buffer_slot_t;Every state change logs:

- Which buffer changed state

- What sequence ID it was serving

- When the transition occurred (tick count)

This means when you see garbage bars, you can grep logs for that sequence ID and reconstruct the entire buffer lifecycle. Did it get released too early? Was it never marked COPYING? Was there a double-allocation?

Debuggability is the contract's audit trail.

Another critical implementation detail: ring size. We settled on 12 buffers. Why? Not because we calculated some theoretical maximum based on producer/consumer rates. Because burst mode requires it.

When the system captures multiple frames back-to-back (e.g., motion-triggered event), the camera might fill several buffers before the first offload completes. With only 3-4 buffers, you'd stall the camera waiting for offload. With 12, you can queue an entire burst while background offload catches up.

Ring sizing is about burst capacity, not just steady-state throughput.

Real-World Usage: Multi-Device Coordination

In a multi-device ecosystem like Hoomanely's—where an EverBowl captures visual data, an EverHub aggregates it, and a Tracker provides motion context—buffer ownership becomes even more complex.

Consider what happens when the EverBowl transmits image data over CAN FD to the EverHub. The EverBowl's ring buffer isn't just feeding local flash storage. It's also feeding a network transmitter with its own buffering and flow control.

Does the EverBowl wait for CAN transmission to complete before releasing buffers? No—that would serialize local storage and network transmission, destroying throughput. Instead, we use layered contracts:

- Ring buffer contract: Release when flash write completes (local)

- Flash storage contract: Hold data until CAN confirms transmission (network)

- CAN transmission contract: Mark flash entries as "sent" after ACK (remote)

Each layer owns a different resource (DRAM, flash, network), with different release conditions. The ring buffer doesn't care about CAN. Flash storage doesn't care about DMA. Each contract is isolated and composable.

This is how you build systems that scale. Not by making one giant state machine that knows about every dependency, but by layering contracts that each solve one ownership problem cleanly.

Another real-world consideration: error handling. What if flash write fails? The ring buffer is already released. The data is lost.

Our solution: conditional release. If offload fails, mark the buffer QUEUED (not RELEASED) and retry. Only transition to RELEASED on success. This means buffer pressure builds during flash errors—eventually stalling the camera—but it preserves data integrity. Explicit backpressure is better than silent data loss.

Takeaways: State Machines as Ownership Contracts

If you take one thing from this article, make it this: Ring buffers without state machines are just circular arrays that make race conditions harder to debug.

Key lessons:

1. Release timing defines correctness, not just performance.

Releasing too early causes corruption. Releasing too late causes stalls. The contract must specify exactly when resources transfer ownership.

2. Make state transitions observable.

Log every transition with timestamps and sequence IDs. When debugging, you need to reconstruct what happened, not guess.

3. Size for bursts, not just steady-state.

Your ring needs enough capacity to absorb temporary spikes in producer rate while slower consumers catch up.

4. Layer contracts, don't centralize them.

Each stage (DMA, PSRAM, flash, CAN) should have its own ownership rules. Compose them, don't merge them into one monolithic state machine.

5. Explicit backpressure beats silent corruption.

If downstream stages can't keep up, stall the producer. Don't drop data silently or overwrite in-flight buffers.

In embedded systems, contracts matter more than code. Your state machine is the contract. Your ring buffer is just the data structure that enforces it.