When Filesystems Became the Bottleneck

Introduction: The Decision We Didn’t Question

When we started building our edge systems, the filesystem was the easiest decision we made.

It was familiar, stable, and came with decades of engineering behind it. Logs went into files. State was persisted as small blobs. Recovery was something the OS already knew how to handle. This wasn’t negligence—it was alignment with what most production systems do.

And at first, everything worked.

The devices behaved predictably. Writes were fast enough. Recovery paths were clear. Nothing about storage felt risky or fragile. If anything, it felt solved.

What changed wasn’t the environment or the requirements. What changed was how closely we started paying attention.

As real workloads accumulated and edge-specific behaviors emerged—frequent small writes, power interruptions, continuous uptime—the filesystem slowly stopped being invisible. It became observable. And eventually, it became the bottleneck.

This article is not about filesystems failing. It’s about what happens when a correct abstraction meets an unforgiving workload—and what we learned when we had to evolve beyond our original assumptions.

The First Signal Wasn’t Failure,It Was Friction

The earliest sign wasn’t corruption or data loss. It was friction.

Certain write paths started taking longer than expected. Not always, not predictably—but often enough to matter. Operations that were once comfortably fast became sensitive to timing. Recovery paths still worked, but they felt heavier.

At first, these were easy to dismiss. Edge systems live in noisy environments. Variability is expected.

But one thing stood out: the workload hadn’t changed.

We weren’t writing more data. We weren’t logging at higher rates. The code paths were the same. Yet storage behavior was slowly diverging from what we designed for.

That inconsistency forced us to stop treating storage as a black box and start observing it as a system component with its own dynamics—latency, amplification, and aging behavior included.

Filesystems Did Exactly What They’re Supposed To

It’s important to be precise here: the filesystem was not misbehaving.

It provided:

- Crash consistency

- Structured recovery

- Human-readable artifacts

- Predictable semantics

All of that mattered—and still does.

The problem was that our workload stressed the filesystem in ways that weren’t obvious at the API level. We had a pattern of frequent, small, meaningful updates:

- State transitions

- Progress markers

- Calibration values

- Health and heartbeat metadata

Individually, these writes were tiny. Logically, they were cheap. But physically, each update triggered metadata churn, journaling activity, and block-level rewrites.

What looked like a simple state update at the application layer translated into a cascade of writes underneath. Over time, that amplification became visible—not as a single failure, but as a gradual loss of headroom.

The filesystem wasn’t wrong.

Our expectations were incomplete.

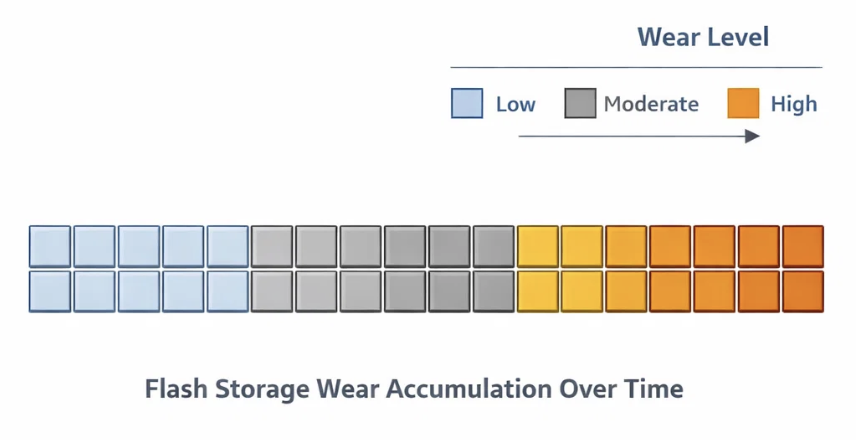

Aging Isn’t a Bug,It’s a Property

One of the harder lessons was accepting that storage wear doesn’t present itself cleanly.

There’s no sharp edge where a system goes from healthy to broken. Instead:

- Latency distributions widen

- Erase operations become more expensive

- Recovery paths accumulate invisible work

By the time corruption shows up, the real damage has already been done.

For edge systems - especially those designed to run unattended : this matters. Reliability isn’t just about correctness today; it’s about how behavior changes tomorrow.

At Hoomanely, we care deeply about graceful degradation. If a system is going to age, it should do so predictably. That meant storage couldn’t remain an implicit dependency. It had to become an explicit design concern.

The Moment We Stopped Chasing Abstractions

Our instinctive reaction wasn’t to remove the filesystem. It was to understand what we actually needed from storage.

We wanted:

- Fast, deterministic writes for critical state

- Clear recovery semantics under power loss

- Minimal write amplification

- Storage behavior that didn’t drift over time

Filesystems optimize for generality. Our needs were specific.

That led us to a realization that shaped everything that followed:

Some data wants structure. Some data wants intent.

And those two don’t always belong in the same abstraction.

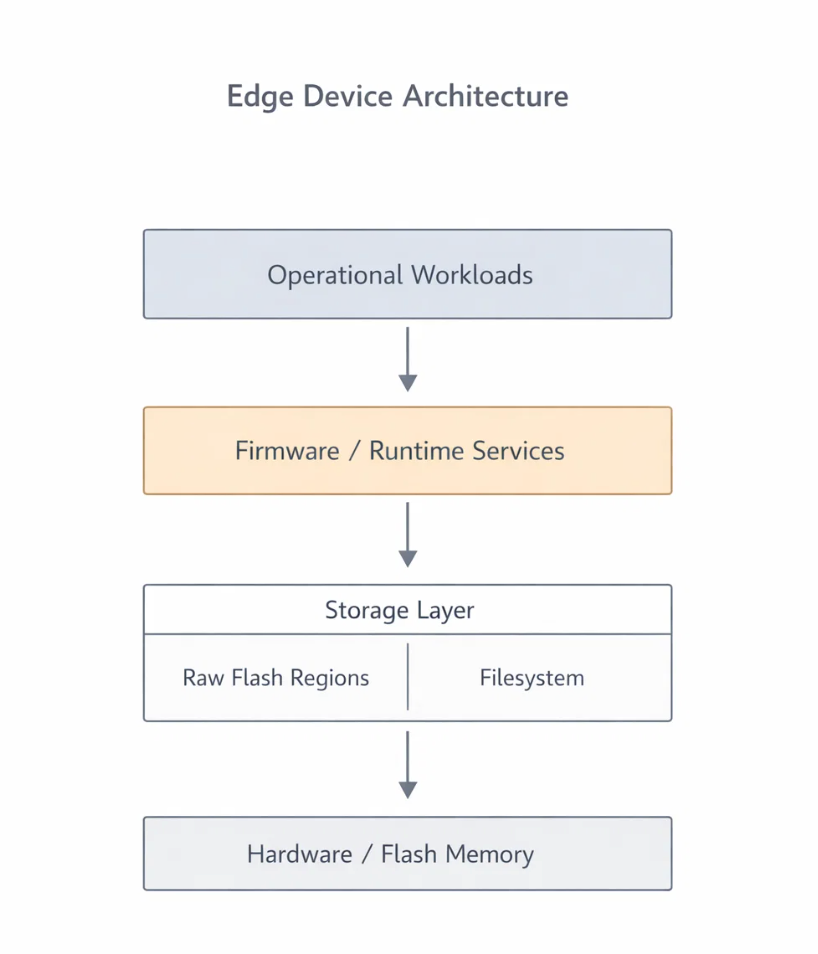

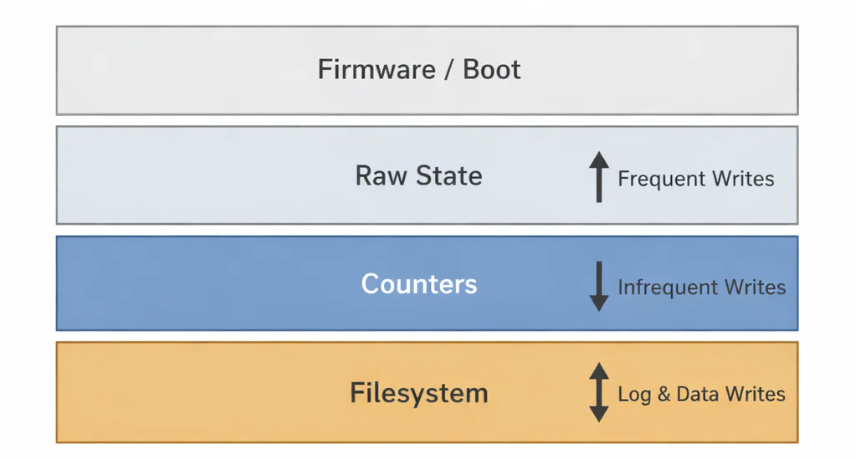

Moving Toward a Hybrid Model

The shift wasn’t dramatic. It was incremental and cautious.

We kept the filesystem where it made sense:

- Logs

- Bulk data

- Artifacts meant for inspection or upload

But for high-frequency, low-entropy state the data that changed often and mattered deeply we moved to controlled raw writes.

This wasn’t about performance alone. It was about ownership.

Raw storage forced us to be explicit:

- What gets written

- When it gets written

- How it’s validated

- How it’s recovered

That responsibility came with risk but also with clarity.

The New Problems We Created

The hybrid approach solved some issues and introduced new ones.

Without the filesystem:

- Recovery logic was ours to design

- Validation had to be explicit

- Debugging required better tooling

We had traded convenience for determinism.

Early versions were fragile. Recovery logic had edge cases. Corruption wasn’t masked by abstractions anymore it was visible. That visibility was uncomfortable, but necessary.

Over time, we introduced structure back in not through a filesystem, but through contracts:

- Append-only records

- Versioned state

- Explicit commit markers

- CRCs tied to intent, not blocks

The difference was control. Every write had a reason. Every recovery path was intentional.

Filesystems Still Matter,Just Not Everywhere

One of the biggest misconceptions we had to unlearn was that this was an “either/or” decision.

It wasn’t.

Filesystems remain essential:

- They give us observability

- They simplify bulk data handling

- They make debugging human

But they work best when they aren’t forced to carry high-churn, latency-sensitive state.

The moment we stopped treating the filesystem as a universal solution, its reliability improved as well. Fewer forced writes meant less pressure, less amplification, and more predictable behavior.

The system didn’t just get faster. It got calmer.

What This Changed for Us at Hoomanely

This experience reshaped how we think about storage architecture.

Today, we design storage the same way we design networking or recovery pipelines:

- With explicit contracts

- With clear ownership

- With failure in mind

Hybrid storage isn’t a trick or an optimization. It’s a recognition that different data has different lifetimes, different meanings, and different failure modes.

By respecting that, we build systems that age more gracefully and fail more honestly.

Key Takeaways

- Filesystems rarely fail outright they erode under mismatched workloads

- Performance degradation is often the first signal of wear

- Hybrid storage models are about intent, not speed

- Owning recovery logic is harder but clearer

- Longevity is an architectural decision, not a configuration option

Final Thought:

The filesystem didn’t become the bottleneck because it was wrong.

It became the bottleneck because our system grew up.