Why Weight Pipelines Break: Designing Stable, Low-Drift Load-Cell Systems with the ADS1234

If you’ve ever shipped a long-running embedded product that relies on stable weight readings, you’ve likely learned a painful truth: load-cell systems rarely fail in the analog domain first they fail in firmware. Not because firmware is the root cause, but because firmware is the first place the failure becomes visible, measurable, and undeniable.

This is a story about those symptoms.

At Hoomanely, where EverBowl infers pet behavior from subtle weight changes, we spent months chasing failures that seemed like firmware bugs: drifting baselines, noisy channels, overnight saturation, “random” full-scale spikes, and measurements that got worse the longer the device ran.

But the more we instrumented the system, the more firmware revealed a deeper pattern:

weight pipelines break long before the MCU realizes it and firmware must be designed to detect, tolerate, and heal those failures.

This article explains how we discovered that, what the firmware saw, how logs misled us, and how we built a more resilient system around the ADS1234.

Problem: Firmware Sees Symptoms Before Anyone Sees Causes

Most failures in weight systems show up first as firmware anomalies, not hardware faults.

We saw:

- Slowly climbing “zero” values

- Sudden full-scale readings without warning

- Weight flattening into a plateau

- Rare spikes that filters couldn’t smooth out

- Channels that looked alive but weren’t changing

- Channels that changed too much

- Drift only after long uptime

- Noise that only appeared in “busy” firmware cycles

For every symptom, firmware initially blamed itself:

Is the ISR late? Did the sample queue overflow? Is the filter too slow? Did a thread preempt something critical?

In reality, firmware wasn’t the cause.

But firmware was the battlefield where every failure surfaced.

Why It Matters: Firmware Is the Layer That Must Keep the System Honest

In Hoomanely’s ecosystem:

- EverBowl uses weight patterns to infer feeding, licking, drinking, and micro-behaviors.

- EverHub aggregates weight telemetry before forwarding to cloud models.

- Even Tracker occasionally relies on stable analog performance for environmental sensors.

If weight data drifts or saturates, every upstream insight becomes misleading.

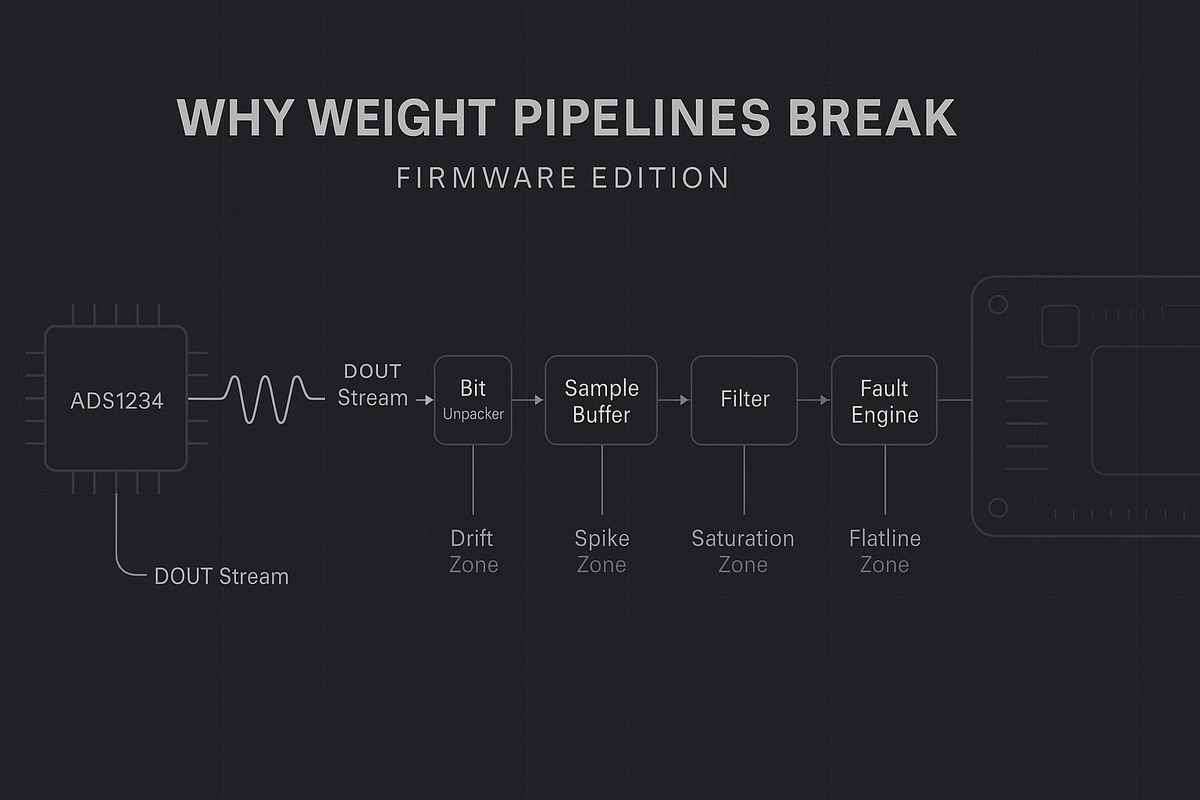

Architecture: How Weight Pipelines Actually Break

Here are the specific firmware-side patterns we saw, and how they mapped back to deeper architectural issues.

1. Slow Drift That Looked Like Environmental Change

The firmware logs told a compelling story:

the baseline was creeping up a few units every hour.

The filters interpreted it as long-term “trend.”

The inference engine interpreted it as pet behavior.

The UI interpreted it as consumption.

Firmware logic said:

Maybe the load cell is warming slightly. Maybe it's humidity. Maybe the filter window is too small.

Reality?

Reference path drift that firmware mistook for genuine motion.

The firmware mistake was trusting a “stable enough” value for too long.

Firmware Lesson

All long-term drift must be treated as a fault until proven otherwise.

Not as behavior.

2. Sudden Full-Scale Saturation That Looked Like Overflow

We saw this symptom many times:

in a single sample, the ADC output jumped to max value and stayed there.

Firmware mistake #1:

“Maybe the scaling calculation overflowed.”

Firmware mistake #2:

“Maybe the ADS1234 read function got garbage.”

Firmware mistake #3:

“Maybe the queue was overwritten.”

What actually happened?

Differential imbalance at the analog bridge.

But firmware felt like it was its own fault.

Firmware Lesson

When ADC rails instantly, assume hardware saturation — not firmware math.

Your code is rarely the cause of a perfect max reading.

3. Rare Single-Sample Spikes That Defeated Every Filter

One of the most frustrating failures was the “ghost spike”:

a single outlier that escaped even large averaging windows.

Firmware designers assumed:

- the ISR was jittering

- thread scheduling caused a delay

- DMA timing got skewed

- a stack overflow corrupted a buffer

We instrumented timestamps, queue sizes, ISR entry times — nothing was wrong.

The true cause:

ADC sampling landed on an unlucky phase relative to a switching regulator.

But firmware was the first to see the spike.

Firmware Lesson

Filters must distinguish between noise and fault signatures.

Spike detection is a diagnostic tool, not just a smoothing function.

4. “Flatline” Channels That Looked Like Dead Threads

Sometimes a weight channel stopped changing entirely — no noise, no drift, just a flat line.

Firmware assumptions:

- ISR stopped firing

- a task was stuck

- a mutex deadlocked

- the sample buffer froze

- power mode suspended the ADC

- the scheduler starved a thread

We traced logs, instrumented thread timeslices, verified queue depth — firmware was healthy.

The actual cause:

One arm of the load cell lost continuity. The ADC saw a perfect, unchanging differential.

Firmware couldn’t detect the fault without architectural help.

Firmware Lesson

Flat readings require fault-detection logic.

Stability is not always success.

5. Noise That Only Appeared When Firmware Was “Busy”

This was a strange one:

Noise increased when CPU load increased.

Firmware blamed itself:

- maybe a task was delaying reads

- maybe the timestamp jitter leaked into sampling

- maybe queue consumption wasn’t keeping up

All wrong.

The real cause was analog ground bounce due to higher digital activity.

But firmware saw a correlation and assumed causation.

Firmware Lesson

Telemetry correlation ≠ root cause.

Just because CPU load and noise move together doesn’t mean firmware caused noise.

6. Filtering Pipelines Amplifying Problems Instead of Fixing Them

One of the harshest discoveries:

Our early filters amplified analog problems.

Examples:

- Averaging windows hid drift until it was too late to correct

- Filters locked onto the wrong state after a saturation event

- Moving medians discarded valuable “fault clues”

- Outlier rejection prevented firmware from seeing the true underlying failure

Filtering is a double-edged sword.

It can smooth the signal or blind you.

Firmware Lesson

Filters must help identify failures, not just hide noise.

Implementation: How We Debugged Failures Using Firmware Telemetry

This section is the heart of firmware storytelling:

what the code and logs told us, what we initially believed, and how we uncovered the true failure mode.

Case Story #1 — The “Drift That Looked Like Behavior Change”

Symptoms in firmware:

- slow upward movement of baseline

- filters treated it as a trend

- weight analytics misinterpreted it as extended feeding

What firmware revealed after instrumentation:

- drift correlated with board temperature

- drift persisted even when input was stable

- re-baselining temporarily resolved the issue

Root cause:

reference path drift.

Firmware takeaway:

We added a “drift detector” that tracks long-term monotonic change and flags it as a reference-domain anomaly, not behavior.

Case Story #2 — The “Channel Flatline That Looked Like Stable Weight”

Firmware initially celebrated:

a perfectly stable reading.

But stable readings over long periods with zero noise should never happen.

Noise is a sign of life.

Firmware tools that solved it:

- variance monitoring

- minimum noise floor enforcement

- stuck-value timers

Root cause:

load-cell path failure, discovered only because firmware refused to trust a “too perfect” signal.

Case Story #3 — The “Spikes That Survived Every Filter”

Firmware logs showed rare but massive outliers.

We suspected concurrency bugs.

Debug tools we added:

- timestamping every sample

- ISR jitter measurement

- circular-buffers with monotonic read tracking

- “previous N samples” error analysis

After ruling out firmware, we correlated outliers with:

- specific PWM activity

- specific regulator phase changes

- temperature thresholds

Root cause:

sampling occurring during a noisy regulator phase.

Case Story #4 — The “Saturation That Looked Like Integer Overflow”

Firmware mistake:

blaming code.

Actual debug steps:

- Logged raw ADC codes before scaling

- Added “saturation counters” per channel

- Added “recovery attempts” and measured return behavior

- Compared saturation timing across devices

Insight:

devices that saturated earlier had more mechanical stress in the connector.

Root cause:

differential imbalance.

Firmware conclusion:

Saturation isn’t a math bug — it's a hardware signature.

Real-World Usage: How Firmware Must Be Designed for Fragile Analog Systems

Here are the patterns that consistently improved field reliability.

1. Firmware Must Never Trust a Value Without Context

Every sample must come with context:

- drift state

- noise signature

- last saturation time

- temperature trend

- variance window

- stuck-value history

Raw weight is not enough.

Metadata is what saves you.

2. Build Filters That Reveal Failures, Not Hide Them

Good firmware filters:

- keep short windows for responsiveness

- keep long windows for drift detection

- understand when the state is invalid

- reject impossible transitions

- surface anomalies instead of smoothing them away

Filtering is a diagnostic system, not just a smoothing system.

3. Firmware Must Validate the Analog Domain Using Logic

Examples:

- A completely stable value for too long = fault

- A monotonic drift without user interaction = fault

- A sudden jump to rail = fault

- Zero variance across hundreds of samples = fault

- Noise floor below expected = possible disconnection

- Spikes matching exactly periodic intervals = coupling signature

Software can catch what hardware doesn't notice.

4. Implement Multi-Stage Fault Handling

Our most robust pipeline uses:

Stage 1 — Fast sanity checks

Reject impossible values immediately.

Stage 2 — Slow behavioral checks

Detect drift, stuck values, creeping anomalies.

Stage 3 — Recovery actions

Re-baseline, reset ADC interface, widen filter windows.

Stage 4 — Persistent-fault escalation

Flag channel as degraded, notify upper layers, adjust inference.

5. Use Firmware to Correlate Across Signals

We correlated weight anomalies with:

- CPU load

- Wi-Fi bursts

- temperature logs

- peripheral activity logs

- power mode transitions

These correlations exposed failure patterns impossible to find from hardware alone.

6. Build Self-Healing Systems

When saturation happened, firmware didn’t reboot — it performed:

- a controlled ADC reset

- re-baseline

- short-term higher-frequency sampling

- recovery verification

- return-to-normal mode

These strategies prevented long-term corrupt data from ever hitting inference.

Takeaways: Firmware Is the First Responder in Analog Failure

1. Firmware sees failures before anyone else does.

Drift, spikes, saturation, flatlines — all visible in logs long before hardware suspicion arises.

2. Filters must diagnose, not decorate.

Their job is to inform the system about anomalies, not hide them.

3. Drift is a fault condition, not a slow motion.

If it's monotonic without interaction, firmware must flag it.

4. Stable readings are suspicious.

Zero variance = hardware or mechanical failure.

5. Correlation is the firmware superpower.

By correlating temperature, CPU load, ADC timing, peripheral activity, firmware becomes a detective.

6. Recovery logic should be deliberate, not reactive.

Re-baseline, re-sync clocks, reset ADC, widen filters — firmly controlled, not impulsive.